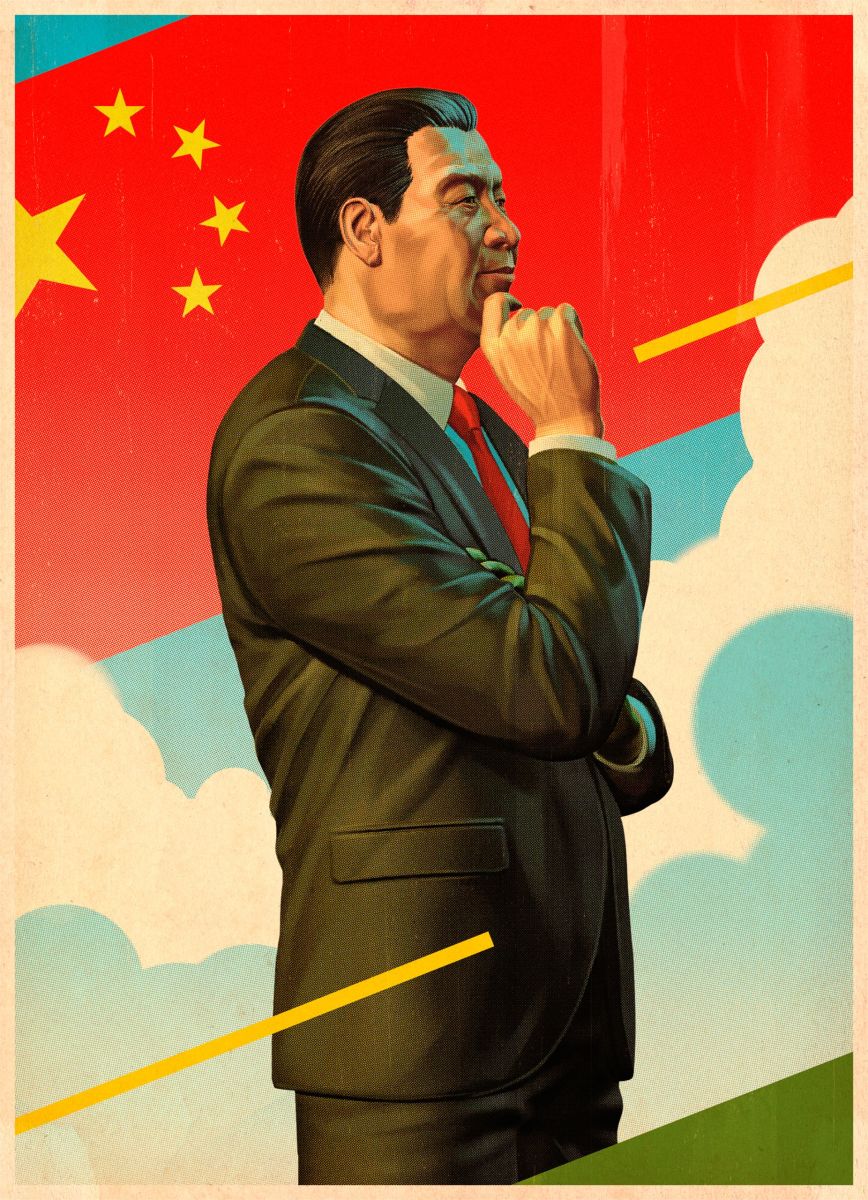

This month saw the second anniversary of Xi Jinping’s accession to China’s presidency, completing the transfer of leadership over Party, military and state. In a broad profile at The New Yorker, Evan Osnos describes Xi’s alternately privileged and perilous upbringing, and the loyalty to the Party he inherited from his revolutionary father; his rapid consolidation of power and vigorous campaigns against corruption, Western influence, and civil society; the meticulous image crafting that has helped him build public support; and, following similar debate sparked by China scholar David Shambaugh, whether Xi’s aggressive leadership will fortify Party rule, or help bring about its demise.

[… A] quarter of the way through his ten-year term, he has emerged as the most authoritarian leader since Chairman Mao. In the name of protection and purity, he has investigated tens of thousands of his countrymen, on charges ranging from corruption to leaking state secrets and inciting the overthrow of the state. He has acquired or created ten titles for himself, including not only head of state and head of the military but also leader of the Party’s most powerful committees—on foreign policy, Taiwan, and the economy. He has installed himself as the head of new bodies overseeing the Internet, government restructuring, national security, and military reform, and he has effectively taken over the courts, the police, and the secret police. “He’s at the center of everything,” Gary Locke, the former American Ambassador to Beijing, told me.

[…] Xi describes his essential project as a rescue: he must save the People’s Republic and the Communist Party before they are swamped by corruption; environmental pollution; unrest in Hong Kong, Xinjiang, and other regions; and the pressures imposed by an economy that is growing more slowly than at any time since 1990 (though still at about seven per cent, the fastest pace of any major country). “The tasks our Party faces in reform, development, and stability are more onerous than ever, and the conflicts, dangers, and challenges are more numerous than ever,” Xi told the Politburo, in October. In 2014, the government arrested nearly a thousand members of civil society, more than in any year since the mid-nineteen-nineties, following the Tiananmen Square massacre, according to Chinese Human Rights Defenders, a Hong Kong-based advocacy group.

[…] For a generation, the Communist Party forged a political consensus built on economic growth and legal ambiguity. Liberal activists and corrupt bureaucrats learned to skirt (or flout) legal boundaries, because the Party objected only intermittently. Today, Xi has indicated that consensus, beyond the Party élite, is superfluous—or, at least, less reliable than a hard boundary between enemies and friends. [Source]

Osnos describes the apparent collapse of the post-Mao convention of collective leadership under Xi. In an assessment of his first two years by AFP’s Felicia Sonmez and Kelly Olsen earlier this month, Claremont McKenna College professor Minxin Pei commented that “if anybody had had any inkling of what was going to happen, [Xi] would not have been picked”:

After the death in 1976 of Communist China’s founding father Mao Zedong — who was at the center of a huge personality cult — the party became deeply conservative politically, Pei said, with its innermost circle selecting top leaders who would respect a new set of norms.

There was to be a consensus-based decision-making process, a respect for the physical safety of other party members and — crucially — no strong leaders.

“Both Jiang and Hu were in that mould,” Pei said, noting that other than Xi, the six remaining members of the party’s elite Politburo Standing Committee “are people who will not rock the boat.”

But Pei added: “In the case of Xi, they’ve got the mother of all boat-rockers. The people who picked him must be regretting bitterly that they picked somebody who turned out to be completely different.” [Source]

Writing at East Asia Forum, though, Renmin University’s Yang Guangbin argued that Xi’s political dominance would be vital in ensuring the Party reaches the centenary of its rule in 2049:

Xi set up his new mode of governance by rebuilding political authority. He established new institutions and authorities to expand his power and maintain control. These new institutions include the Leading Group for Deepening Reform Comprehensively; the National Security Commission, which former party general secretary Jiang Zemin was unable to establish; and a leading group for cybersecurity and information.

Xi is in charge of all these new institutions. This means that all the institutions of the party, State Council and military are now responsible to Xi and only Xi. As a result, he acts as the de facto party Chairman – like Mao Zedong.

Xi also expanded the scope of party authority. In the 1980s, the State Council controlled the leading institutions of reform. Now it comes under the party’s Central Committee. While the State Council was almost entirely self-governed during Hu’s tenure, Xi has regained control of the reform agenda through his new institutions.

[…] While the details of how Xi rebuilt authority are likely to remain shrouded, the anti-corruption campaign has served as one well-known method. With dirty officials tripping each other up, the campaign has acted as a broom, removing the obstacles to reform. [Source]

At The Diplomat, however, Chatham House’s Kerry Brown dismissed even the anti-corruption campaign as “froth”:

It has become accepted wisdom now to say that Xi Jinping is the most powerful leader China has had since Deng Xiaoping. This is almost certainly something that Xi himself would not thank people for pointing out. As the National People’s Congress (NPC) in 2015 has made patently clear, the promises made by the leadership that he sits at the heart of are hostages to fortune — every single one of them. A quarter of the way through his likely time in office, the question is beginning to be raise: when do the real achievements start? Xi has been given all the trappings of power, but is he truly using his titles to make a lasting impact?

The signature themes of this leadership are better quality growth, green and sustainable development, and national self-confidence and status. The Congress addressed all of those items, carrying on from the Plenums of 2013 and 2014. There was plenty of coherence and consistency, certainly. But a nagging question started to raise its head over the first week of March as the two meetings (the NPC and the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference) were going on: where is the implementation? When is the good news about successful outcomes going to start? Beijing’s pollution continued to be a visible reminder of how entrenched some problems are. And the drama of the anti-corruption campaign, while it shows the muscular side of power, is froth on the surface. For the 1.3 billion people across China, how do they feel their lives are doing under the new leadership? This is the one question that Xi and co. need to fear the answer to. [Source]