Late last week, Bloomberg’s Jordan Robertson and Michael Riley published stunning claims that computer servers at nearly 30 American companies including Apple and Amazon had been compromised at the hardware level by Chinese manufacturers operating under official instructions. No consumer hardware is alleged to have been affected. While security experts have long warned of such vulnerabilities, the Bloomberg story has faced flat denials from companies involved, with British and American intelligence agencies speaking out to support them, and other observers raising an array of technical and other objections. From the original report:

There are two ways for spies to alter the guts of computer equipment. One, known as interdiction, consists of manipulating devices as they’re in transit from manufacturer to customer. This approach is favored by U.S. spy agencies, according to documents leaked by former National Security Agency contractor Edward Snowden. The other method involves seeding changes from the very beginning.

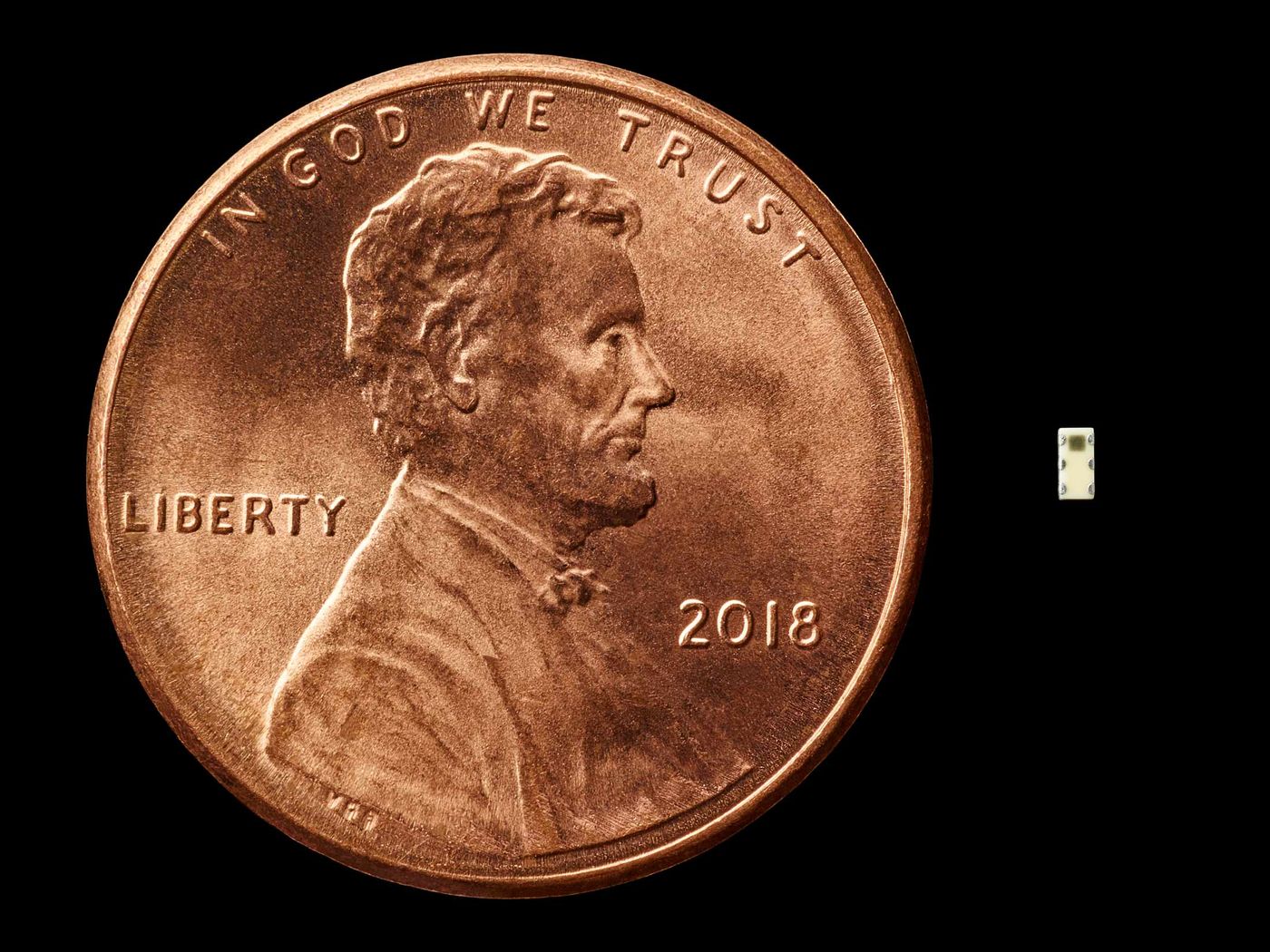

One country in particular has an advantage executing this kind of attack: China, which by some estimates makes 75 percent of the world’s mobile phones and 90 percent of its PCs. Still, to actually accomplish a seeding attack would mean developing a deep understanding of a product’s design, manipulating components at the factory, and ensuring that the doctored devices made it through the global logistics chain to the desired location—a feat akin to throwing a stick in the Yangtze River upstream from Shanghai and ensuring that it washes ashore in Seattle. “Having a well-done, nation-state-level hardware implant surface would be like witnessing a unicorn jumping over a rainbow,” says Joe Grand, a hardware hacker and the founder of Grand Idea Studio Inc. “Hardware is just so far off the radar, it’s almost treated like black magic.”

[…] The companies’ denials are countered by six current and former senior national security officials, who—in conversations that began during the Obama administration and continued under the Trump administration—detailed the discovery of the chips and the government’s investigation. One of those officials and two people inside AWS provided extensive information on how the attack played out at Elemental and Amazon; the official and one of the insiders also described Amazon’s cooperation with the government investigation. In addition to the three Apple insiders, four of the six U.S. officials confirmed that Apple was a victim. In all, 17 people confirmed the manipulation of Supermicro’s hardware and other elements of the attacks. The sources were granted anonymity because of the sensitive, and in some cases classified, nature of the information. [Source]

Supply chain integrity fears recently arose around the Chinese manufacturer of Google-branded security key hardware.

Bloomberg followed up this week with a second report alleging the discovery of compromised Ethernet ports on Supermicro servers by an unidentified "major U.S. telecommunications company," this time citing a named source, former Israeli intelligence officer Yossi Appleboum.

A major U.S. telecommunications company discovered manipulated hardware from Super Micro Computer Inc. in its network and removed it in August, fresh evidence of tampering in China of critical technology components bound for the U.S., according to a security expert working for the telecom company.

[…] The executive said he has seen similar manipulations of different vendors’ computer hardware made by contractors in China, not just products from Supermicro. “Supermicro is a victim — so is everyone else,” he said. Appleboum said his concern is that there are countless points in the supply chain in China where manipulations can be introduced, and deducing them can in many cases be impossible. “That’s the problem with the Chinese supply chain,” he said.

[…] The more recent manipulation is different from the one described in the Bloomberg Businessweek report last week, but it shares key characteristics: They’re both designed to give attackers invisible access to data on a computer network in which the server is installed; and the alterations were found to have been made at the factory as the motherboard was being produced by a Supermicro subcontractor in China. [Source]

The first report included denials from both Amazon Web Services and Apple, two of the nearly thirty American companies said to have been affected. Bloomberg posted the companies’ statements in full, separately, together with others from SuperMicro and China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs. From Apple’s statement:

It’s untrue that AWS knew about a supply chain compromise, an issue with malicious chips, or hardware modifications when acquiring Elemental. It’s also untrue that AWS knew about servers containing malicious chips or modifications in data centers based in China, or that AWS worked with the FBI to investigate or provide data about malicious hardware. [Source]

From Amazon’s:

Over the course of the past year, Bloomberg has contacted us multiple times with claims, sometimes vague and sometimes elaborate, of an alleged security incident at Apple. Each time, we have conducted rigorous internal investigations based on their inquiries and each time we have found absolutely no evidence to support any of them. We have repeatedly and consistently offered factual responses, on the record, refuting virtually every aspect of Bloomberg’s story relating to Apple.

On this we can be very clear: Apple has never found malicious chips, “hardware manipulations” or vulnerabilities purposely planted in any server. Apple never had any contact with the FBI or any other agency about such an incident. We are not aware of any investigation by the FBI, nor are our contacts in law enforcement. [Source]

Both companies quickly followed up with further disavowals after the first article’s publication. Apple then tripled down with a letter to the Senate and House commerce committees from its Vice President for Information Security stating that “Apple’s proprietary security tools are continuously scanning for precisely this kind of outbound traffic, as it indicates the existence of malware or other malicious activity. Nothing was ever found.”

The bluntness and falsifiability of Apple’s denials, in particular, struck many observers. Apple blogger John Gruber alluded to the company’s frequent policy of declining to comment on news stories, writing that "in my experience, Apple PR does not lie. Do they spin the truth in ways that favor the company? Of course. That’s their job. But they don’t lie [….] They’d say nothing before they’d lie."

Technology journalist Kim Zetter commented:

I have to say, this is all really bizarre. The Bloomberg story is very detailed, citing documents and inside sources. But the company denials are also detailed and emphatic. You don't often see the latter when a company is trying to hide something or be coy. https://t.co/qjA1TFKzZ3

— Kim Zetter (@KimZetter) October 4, 2018

I've been a reporter for 15 years. The statements from Apple and Amazon are not the kinds of statements you get when the spokespeople are being kept in the dark.

— Kim Zetter (@KimZetter) October 4, 2018

An NSL would cause a company to say no comment or some variation of that. It would not lead them to release the kind of statements these companies released.

— Kim Zetter (@KimZetter) October 4, 2018

David Vladeck, former head of the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, noted the potential costs of a dishonest denial in an email to Axios, saying that "the companies [would] risk enforcement by the FTC for engaging in a deceptive act that is likely to harm consumers. […] I am strongly disinclined to think they are lying.”

Reuters’ Guy Faulconbridge and Joseph Menn also reported a denial by Apple’s former chief lawyer:

Apple’s recently retired general counsel, Bruce Sewell, told Reuters he called the FBI’s then-general counsel James Baker last year after being told by Bloomberg of an open investigation into Super Micro Computer Inc , a hardware maker whose products Bloomberg said were implanted with malicious Chinese chips.

“I got on the phone with him personally and said, ‘Do you know anything about this?,” Sewell said of his conversation with Baker. “He said, ‘I’ve never heard of this, but give me 24 hours to make sure.’ He called me back 24 hours later and said ‘Nobody here knows what this story is about.’”

Baker and the FBI declined to comment Friday. [Source]

The report noted that the National Cyber Security Centre at British signals intelligence agency GCHQ had commented that, "We are aware of the media reports but at this stage have no reason to doubt the detailed assessments made by [Amazon Web Services] and Apple." The U.S. Department of Homeland Security issued a similar statement on Saturday. Bloomberg responded that the DHS would not necessarily be familiar with the content of a heavily siloed FBI counterintelligence investigation. Nevertheless, the DHS statement was the last straw for some observers. Johns Hopkins’ Thomas Rid tweeted that he was "filing the ‘Chinese hardware hack’ as a hoax until further notice," adding that "Bloomberg’s credibility on infosec stories is seriously damaged by now. An official reaction would be in order imho." Security expert "The Grugq" advised followers to “put a fork in it.”

Further blows followed. On Wednesday, the NSA’s Dan Joyce, who returned to the agency earlier this year after a stint as a White House cybersecurity adviser, told Dustin Volz at The Wall Street Journal that he had also been able to find corroboration despite his wide-ranging access:

Joyce: “We’re befuddled” about the Bloomberg article. Says he has great access to intel and hasn’t found corroboration of the story last week or the new one on telcos, says there is “great frustration” in government about the stories.

— Dustin Volz (@dnvolz) October 10, 2018

In further comments from Politico, quoted at 9to5Mac, Joyce said that "I’ve got all sorts of commercial industry freaking out and just losing their minds about this concern, and nobody’s found anything. … There’s no there there yet […] Those companies will ‘suffer a world of hurt’ if regulators later determine that they lied. [… I have] grave concerns about where this has taken us […] I worry that we’re chasing shadows right now. I worry about the distraction that it is causing."

FBI director Christopher Wray told the Senate Homeland Security Committee on Wednesday that “we have very specific policy that applies to us as law enforcement agencies to neither confirm nor deny the existence of an investigation,” adding that “I do want to be careful that my comment not be construed as inferring, or implying I should say, that there is an investigation. […] Be careful what you read in this context.”

A further blow came from the the Risky Business podcast, where one of the story’s named sources, Joe Fitzpatrick, expressed several reservations, describing technical details in the piece as "jumbled" and saying that details he had provided were presented out of context. Bloomberg’s account, he said, "doesn’t make sense because there are so many easier ways to do it. There are so many easier hardware ways to do it, there are software, there are firmware approaches, and the approach that you’re describing [is] not scalable, it’s not logical." (Host Patrick Gray, who had previously withdrawn an endorsement of the report after an independent source retracted its supporting statements, returned to "Bloomberg’s dumpster fire" and past record on information security at greater length in a later episode.)

At Ars Technica, Dan Goodin cited similar suggestions that tampering with hardware might simply be unnecessary when the same ends could be achieved more easily and economically in software, with lower risk of discovery.

“Attackers tend to prefer the lowest-hanging fruit that gets them the best access for the longest period of time,” Steve Lord, a researcher specializing in hardware hacking and co-founder of UK conference 44CON, told me. “Hardware attacks could provide very long lifetimes but are very high up the tree in terms of cost to implement.”

He continued:

Once discovered, such an attack would be burned for every affected board as people would replace them. Additionally, such a backdoor would have to be very carefully designed to work regardless of future (legit) system firmware upgrades, as the implant could cause damage to a system, which in turn would lead to a loss of capability and possible discovery.

[…] Lord was one of several researchers who unearthed a variety of serious vulnerabilities and weaknesses in Supermicro motherboard firmware (PDF) in 2013 and 2014. This time frame closely aligns with the 2014 to 2015 hardware attacks Bloomberg reported. Chief among the Supermicro weaknesses, the firmware update process didn’t use digital signing to ensure only authorized versions were installed. The failure to offer such a basic safeguard would have made it easy for attackers to install malicious firmware on Supermicro motherboards that would have done the same things Bloomberg says the hardware implants did.

[…] “I spoke with Jordan a few months ago,” [security firm Rapid7’s chief research officer HD] Moore said, referring to Jordan Robertson, one of two reporters whose names appears on the Bloomberg articles. “We chatted about a bunch of things, but I pushed back on the idea that it would be practical to backdoor Supermicro BMCs with hardware, as it is still trivial to do so in software. It would be really silly for someone to add a chip when even a non-subtle change to the flashed firmware would be sufficient.” [Source]

At Serve The Home, Patrick Kennedy raised yet another objection:

[…] Supermicro servers are procured for US Military contracts and use to this day. Supermicro’s government business is nowhere near a large as some other vendors, but there are solutions providers who sell Supermicro platforms into highly sensitive government programs.

If the FBI, or other intelligence officials, had reason to believe Supermicro hardware was compromised, then we would expect it would have taken less than a few years for this procurement to stop.

Assuming the Bloomberg story is accurate, that means that the US intelligence community, during a period spanning two administrations, saw a foreign threat and allowed that threat to infiltrate the US military. If the story is untrue, or incorrect on its technical merits, then it would make sense that Supermicro gear is being used by the US military. [Source]

Meanwhile, the named source for the second Bloomberg report, Yossi Appleboum, told Kennedy that he felt the article had overemphasized the importance of Supermicro in what he described as a far broader problem.

I think [Supermicro] are innocent and someone is using them to dilute the story instead of mitigating the threat. Please help me, them, and everyone else to understand that the problem is bigger. Dealing with this as a Supermicro problem will ruin the opportunity to face the reality that we need to fix it.

[…] I want to be quoted. I am angry and I am nervous and I hate what happened to the story. Everyone misses the main issue. [Source]

Even before the tide had turned against Bloomberg’s report, many had commented that "if it is completely false, it is still a pretty big deal" given the gravity of the theoretical threat and the context of chilling U.S.-China relations and mounting security concerns over Chinese technology abroad. Ian Bogost elaborated on this theme at The Atlantic:

Who is right is a matter of corporate and national security. The exploits and hacks that have rocked the tech industry in recent years would seem minor compared with a foreign state gaining stealth access to the entire networks of companies and government agencies that manage enormous volumes of sensitive information. But even if the situation turns out to be different than Businessweek’s report, the scenario outlined in the piece (or one like it) is totally plausible. That plausibility, made newly visible, could combine with an accelerant: A tough American stance on Chinese business, including President Trump’s love for tariffs and trade war, and China’s increased dedication to independence. The resulting blaze has serious implications for the American technology business, and it won’t soon burn out.

[…] Whether or not a microcontroller backdoor turns out to have been installed somewhere in the Chinese supply chain, the conditions are right for anxiety about that possibility to impact U.S. trade with China in the high-tech industry. The truth of Bloomberg Businessweek’s investigation might matter less than the concerns it opens, or the open worries it further irritates—at the White House, at U.S. regulating bodies, and among the general public.

[…] If China begins to believe that its local manufacturing capabilities will outstrip its reliance on U.S. design, parts, and materials, then the risk associated with hardware-level attacks will lower considerably, while providing substantial benefit in the form of industrial or state espionage. Soon enough, as people start tearing down the Super Micro motherboards at the heart of the scandal, the world will learn whether the hack is a real crisis or a false alarm. But in some ways, it is a real crisis no matter the outcome. [Source]

George Washington University’s Henry Farrell and Georgetown University’s Abraham Newman examined the political implications of supply chain threats immediately after the Bloomberg report’s publication at The Washington Post:

Our academic research explores how countries are increasingly starting to weaponize interdependence — using these vulnerabilities and choke points for strategic advantage. China’s hacking of motherboards is a perfect example of this. As the Bloomberg article recounts, Chinese manufacturers dominate key aspects of computer hardware manufacturing. While some people had been confident that China would never hack exported components en masse — for fear of the damage that it would do to the Chinese economy — the Bloomberg article suggests that they have succumbed to temptation. It should be noted that the United States, too, has used its economic weight against Chinese hardware manufacturers. At one point the United States threatened the Chinese telecommunications giant ZTE with economic sanctions that would have made it impossible to buy chips from manufacturers with exposure to U.S. markets, a move that would effectively have driven ZTE out of business.

If the Bloomberg report is confirmed — and especially if it is one particular example of a broader problem — there will be very big economic repercussions. The U.S. economy and China’s economy are deeply interdependent. If the U.S. believes that Chinese firms are using this interdependence strategically to compromise U.S. technology systems with hardware components that undermine security, there will be pressure on the United States to systematically disengage from China and, perhaps, from global supply chains more generally.

This could have substantial knock-on repercussions for international trade, leading eventually to a world in which countries are much less willing to outsource components of sensitive systems to foreign manufacturers. Because we live in a world where technology is becoming ever more connected and ever more exploitable, this might mean that large swaths of the global economy are pulled back again behind national borders. The United States is already highly suspicious of Chinese telecommunications manufacturers, while organizations closely linked to U.S. intelligence are calling for a far more systematic reappraisal of the security implications of supply chains. In an extreme scenario, it may be that the globalized economy of the 1990s and 2000s was a brief aberration, which will be replaced by more constrained and limited international exchange between economies that keep the important parts of their manufacturing economy at home. [Source]

Security expert Bruce Schneier commented briefly on the issue of supply chain security on his blog:

I’ve written (alternate link) this threat more generally. Supply-chain security is an insurmountably hard problem. Our IT industry is inexorably international, and anyone involved in the process can subvert the security of the end product. No one wants to even think about a US-only anything; prices would multiply many times over.

We cannot trust anyone, yet we have no choice but to trust everyone. No one is ready for the costs that solving this would entail.

[…] Bottom line is that we still don’t know [whether Bloomberg’s reporting was accurate]. I think that precisely exemplifies the greater problem. [Source]

In a subsequent post on the second Bloomberg report, he expressed less confidence than many others in the significance of the various denials, maintaining that "the story is plausible. The denials are about what you’d expect."

Fellow security expert Brian Krebs argued similarly in a longer exploration of supply chain threats on his own blog:

[…] Even if you identify which technology vendors are guilty of supply-chain hacks, it can be difficult to enforce their banishment from the procurement chain. One reason is that it is often tough to tell from the brand name of a given gizmo who actually makes all the multifarious components that go into any one electronic device sold today.

[… T]he issue here isn’t that we can’t trust technology products made in China. Indeed there are numerous examples of other countries — including the United States and its allies — slipping their own “backdoors” into hardware and software products.

Like it or not, the vast majority of electronics are made in China, and this is unlikely to change anytime soon. The central issue is that we don’t have any other choice right now. The reason is that by nearly all accounts it would be punishingly expensive to replicate that manufacturing process here in the United States. [Source]

The New York Times’ Paul Mozur wrote on Friday that suspicion over supply chain security runs both ways between China and the U.S.:

After Edward J. Snowden’s disclosures about how the United States used American companies to spy overseas, China accelerated a campaign to build just about every piece of advanced tech itself. That quest for self-reliance led it to introduce quotas on foreign-made products and require so-called tech transfers for market access. Those policies helped pave the way to the current trade war between the United States and China.

Not surprisingly, the United States has had the same spying concerns as China. Congress effectively blocked China’s Huawei and ZTE from selling their equipment to major telecom carriers in the United States in 2012, and more recently made it harder for Huawei to sell phones.

The fact that the two sides share the same fears shows how difficult it can be to ensure security in a world in which the design, production and assembly of electronics occur across multiple countries.

[…] Neither side is happy with this. Both China and the United States will probably continue to winnow their mutual tech reliance. It won’t be easy. They are working against 40 years of economic integration and a tremendously complex web of big and small companies. [Source]

Meanwhile, a number of other reports have suggested that Chinese economic espionage is resurging after abating in the wake of an agreement secured by the Obama administration in 2015. (The first Bloomberg report described "the White House’s deep concern that China was willing to offer this concession because it was already developing far more advanced and surreptitious forms of hacking founded on its near monopoly of the technology supply chain.") Reuters’ Christopher Bing reported last week, before the Bloomberg article’s publication:

The U.S. government on Wednesday warned that a hacking group widely known as cloudhopper, which Western cybersecurity firms have linked to the Chinese government, has launched attacks on technology service providers in a campaign to steal data from their clients.

The Department of Homeland issued a technical alert for cloudhopper, which it said was engaged in cyber espionage and theft of intellectual property, after experts with two prominent U.S. cybersecurity companies warned earlier this week that Chinese hacking activity has surged amid the escalating trade war between Washington and Beijing.

[…] “I can tell you now unfortunately the Chinese are back,” Dmitri Alperovitch, chief technology officer of U.S. cybersecurity firm CrowdStrike, said Tuesday at a security conference in Washington, D.C.

“We’ve seen a huge pickup in activity over the past year and a half. Nowadays they are the most predominant threat actors we see threatening institutions all over this country and western Europe,” he said.

Analysts with FireEye, another U.S. cybersecurity firm, said that some of the Chinese hacking groups it tracks have become more active in recent months. [Source]

China’s Foreign Ministry has pushed back against these claims:

[Spokesperson Lu Kang] said it is "purely out of ulterior motive that some companies and individuals in the US use so-called cyber theft to blame China for no reason."

"China is one of the main victims of cyber theft and attacks, and a staunch defender of cyber security. China has always firmly opposed to and fought against any forms of cyber attacks and theft," said Lu during a regular press conference.

"According to documents revealed by (US National Security Agency whistleblower) Edward Snowden and others, the international community has long been aware which country had carried out large-scale long-term surveillance of foreign governments, enterprises, and individuals, and who is the world’s largest cyber attacker," he added. [Source]

At Politico EU, however, Laurens Cerulus reported similar concerns from Europe:

The European Commission Thursday met a group of national government experts, foreign affairs officials and industry lobbyists to go over a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers and the Commission department that is likely to lead to EU action in coming months.

The study, an executive summary of which was obtained by POLITICO, offers a peek into “public and private sector concerns about the increasing risks associated with cyber-theft of trade secrets in Europe.”

In the manufacturing sector, it said, industrial espionage and cybertheft of trade secrets constitute up to 94 percent of all cyberattacks. The summary cites estimates that cyber espionage is costing Europe up to €60 billion in economic growth — a figure that would rise as European companies digitize their services.

[…] Europe’s largest business lobby BusinessEurope released a statement Thursday in which it asks the EU to come up with a “strategy to deter hostile actors” like China. “Diplomatic action or economic retaliation could be considered,” the group says, adding that “the EU could seek to cooperate with the United States, Japan and other OECD economies to apply political pressure.” [Source]

On Wednesday, The Washington Post’s Ellen Nakashima reported the possibly unprecedented extradition of a Chinese intelligence officer for stealing commercial secrets:

Yanjun Xu, a senior officer with China’s Ministry of State Security (MSS), is accused of seeking to steal trade secrets from leading aviation firms, top Justice Department officials said. His capture helps vindicate law enforcement officials who have faced criticism in recent years that indictments of foreign operatives are unlikely to result in the defendants setting foot in a courtroom.

Current and former officials said Xu’s extradition is apparently the first time a Chinese government spy has been brought to the United States to face charges.

[…] Justice Department officials said the indictment is the latest example of China seeking to develop its economy at the expense of American firms and know-how. Though China has often used computer hacking to filch secrets, this case relied on traditional espionage techniques, including the attempted recruitment of corporate insiders.

[…] “If not the first, this is an exceptionally rare achievement — that you’re able to catch an espionage operative and have them extradited to the United States,” said John Carlin, a former assistant attorney general for national security. “It significantly raises the stakes for China and is a part of the deterrence program that some people thought would never be possible.” [Source]

At The New York Times, meanwhile, the Council on Foreign Relations’ Adam Segal assessed the risk of covert online Chinese interference in American politics, following accusations of such from the White House. (Read more on these claims from Brian Barrett at Wired, James Palmer at Foreign Policy, and CDT.)

Neither the president nor the vice president charged China with stealing and releasing politically sensitive emails or manipulating social media, as the Russian government appears to have done to sway the 2016 presidential election.

And the Chinese government has not yet tried to use cyberspace to disrupt American elections, it seems. Yet the threat is real.

China has both the playbook and the capacity to interfere. Chinese entities operating with the assent of the government in Beijing already have mounted long-running cyberespionage campaigns against United States government agencies, the defense industry and American private companies. And they have conducted disruptive cyberattacks on political processes and social media campaigns in targets the Chinese government considers internal: Tibet, Hong Kong and Taiwan.

[…] As it watches Washington struggle to find a coherent response to Russian interference in 2016, the Chinese government is likely to think that it could avoid serious repercussions if it ever launched similar cyberattacks in the United States. Were China’s strategic calculations to change, there would be little to stop it from entering the online fray. [Source]