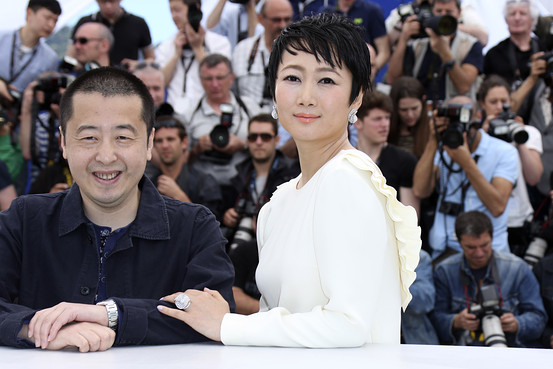

Chinese film director Jia Zhangke, whose lastest film A Touch of Sin has been censored on mainland China and prevented from entering the Oscars, explains why the Chinese authorities have clamped down on his award-winning film. China Real Time reports:

“In theory, it will definitely show. In reality? I talk to [film regulators] basically once every two weeks,” Mr. Jia told China Real Time in a recent interview. He said the film had been basically approved by censors months ago but was still awaiting a final OK. “The official side is a little anxious. [They think] maybe the audience won’t be able to take it. Maybe there will be negative reactions.”

[…] “A Touch of Sin” tells the stories of four people—a villager locked in struggle with corrupt officials and businessmen; a migrant who returns home and ends up hunting the local wealthy; a sauna receptionist who is assaulted by a client; and an unhappy factory worker—all of whom crack under the pressure of injustice and indifference. It’s unusually blunt fare for a Chinese film based largely on real-life stories that spread on Sina Weibo, the popular microblogging platform that has come to serve as both a virtual town square and an alternative, less tightly managed news source.

[…] The director dismissed as “naïve” the argument, often put forth by censors, that Chinese people need to be protected from reality online and in the cinema because it might lead to social disorder. “Life can’t be full of happiness. Culture ought to have a certain load-bearing capacity,” he said [Source]

Despite Jia’s attempts to protect the film from piracy, a pirated version has been leaked online. From The Hollywood Reporter:

An early version of Chinese director Jia Zhangke‘s critically acclaimed film A Touch of Sin turned up on top piracy sites over the weekend. On torrent providers such as The Pirate Bay, the illegal copy has already logged thousands of downloads.

[…] So far, the pirated copy of the film, which doesn’t include subtitles, presents viewers — whether Chinese or international — with some considerable linguistic barriers. The movie’s multiple narratives take place in four far-flung regions of China, from the booming southern megalopolis of Guangzhou to the northern mountainous province of Shanxi. To fully comprehend the film, a viewer would need to understand four Chinese dialects.

Jia says he and his backers at Shanghai Film Studio are pushing on with their campaign to sway the censors.

“I have been working hard to get the movie in theaters. It is something worth doing, and I won’t stop trying,” he posted to his Sina Weibo account. [Source]

Jiayang Fan at The New Yorker looks at how Jia Zhangke’s A Touch of Sin speaks to the dynamics of “violence and vengeance” in contemporary Chinese society, particularly as it pertains to the knife attack at the recent Kunming Railway Station which left twenty-nine people dead and many more wounded.

The four story lines that make up Jia Zhangke’s “A Touch of Sin” were inspired by Weibo, the Chinese version of Twitter. During 2011 and 2012, when Jia was making the film, a string of apparently senseless killings—including several kindergarten rampages—dominated headlines and sparked anguished soul-searching among the horrified public. (For a time, the country’s most popular viral video showed a two-year-old hit-and-run victim bleeding on the roadside, ignored by eighteen people who passed by.) As Christopher Beam argued in a piece that drew a link between Jia’s film and China’s sobering drumbeat of violence: “In a country with no ‘good Samaritan’ laws and a history of victims suing their helpers, [those who walk past without lending a hand] were acting rationally, albeit monstrously.”

It is a chilling thing to be both rational and monstrous: we tend to believe, rightly or wrongly, that inexplicable evil does not involve logic. But it’s hard to determine whether any of these calculations apply to the premeditated attack in Kunming, which quickly came to be known as “China’s 9/11.” Almost immediately after the attack, authorities identified the perpetrators as Uighur separatists from Xinjiang, in the country’s restive northwest. (Reports claimed that police on the scene had recovered a black flag traditionally associated with those who support independence for what some Uighurs call East Turkestan.)

[…] In the past year alone, there have been more than two hundred incidents of violence in Xinjiang. The most high-profile attack, however, took place in Beijing last October, when a jeep deliberately plowed into pedestrians in Tiananmen Square and caught fire, killing the three Uighurs inside, and two pedestrians, while injuring more than forty others. [Source]