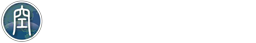

这是今天Science的一篇社论。题目很简单,只有三个单词;篇幅很小,仅一页;但三张图片很值得深思,一张是饶毅 北京大学生命科学学院教授 院长,另一张是施一公 清华大学生命科学学院教授 院长,最左边是一叠叠百元人民币。

近两年,Nature和Science上评论中国科研体制的文章并不少见。但往往都是劝诫工作在科研一线的学生,研究者要正视问题,不同流合污等。但像饶毅教授和施一公教授如此直白、如此一针见血的评论“权贵阶级”、”Policy Maker”仍是头一回!

其实,文章里指出的问题,包括潜规则,下至研究生(部分本科生),上至科技部长……是谁都知道的问题!但这次真是第一次中国最出名的两大高等学府——清华、北大的两位生科院院长在影响力最大的期刊上不拐弯抹角的说出“上层阶级”这些问题。

虽然两位教授的文字里没有提到如何解决问题,因为这两位中国生命科学界的“大佬”也知道个体与群体,以及制度体制、理想与现实的关系,但这篇文章是值得纪念的,也许若干年后总结科研体制改革时,这篇文章即使不算一个里程碑,但至少可以为一个里程碑的建立作以注脚。

即使有时我不是一个敢于说真话的人,但可以为敢说真话的老师鼓掌……

以下转自《科学时报》的译文:

中国政府投入的研究经费以每年超过20%的比例增加,甚至超过了中国最乐观的科学家们的预期。从理论上讲,它应该能让中国在科学和研究领域取得真正突出的进步、与国家的经济成功相辅相成。而现实中,研究经费分配的严重问题却减缓了中国潜在的创新步伐。这些问题部分归结于体制,部分归结于文化。

尽管对于一些比如由中国国家自然科学基金委员会资助的小型研究经费来说,科学优劣可能仍然是能否获得经费的关键因素,但是,对来自政府各部门的巨型项目来说,科学优劣的相关性就小多了,这些项目的经费从几千万元到几亿元人民币。对后者而言,关键问题在于每年针对特定研究领域和项目颁发的申请指南。表面上,这些指南的目的是勾画“国家重大需求”;然而,项目的申请指南却常常被具体而狭隘地描述,人们基本上可以毫无悬念地意识到这些“需求”并非国家真正所需;经费预定给谁基本一目了然。政府官员任命的专家委员会负责编写年度申请指南。因为显而易见的原因,专家委员会的主席们常听从官员们的意见,并与他们合作。所谓“专家意见”不过反映了很小部分官员及其赏识的科学家之间的相互理解。

这种自上而下的方式不仅压抑了创新,也让每个人都很清楚:与个别官员和少数强势科学家搞好关系才最重要,因为他们主宰了经费申请指南制定的全过程。在中国,为了获得重大项目,一个公开的秘密是:作好的研究不如与官员和他们赏识的专家拉关系重要。

中国大多数研究人员常嘲讽这种有缺陷的基金分配体制。然而,一个自相矛盾的现象是,他们中的绝大多数人却也接受了它。部分人认为除了接受这些惯例之外别无选择。这种潜规则文化甚至渗透到那些刚从海外回国学者的意识中:他们很快适应局部环境,并传承和发扬不健康的文化。在中国,相当比率的研究人员花了过多精力拉关系,却没有足够时间参加学术会议、讨论学术问题、作研究或培养学生(甚至不乏将学生当做廉价劳力)。很多人因为太忙而在原单位不见其踪影。有些人本身已成为这种问题的一部分:他们更多地是基于关系,而非学术优劣来评审经费申请者。

无须陈述科学研究和经费管理中的伦理规章,因为绝大多数中国研究界的权势人物都在工业化国家接受过教育。然而,全面改变这一体制并非易事。现行体制的既得利益者拒绝真正意义上的改革;部分反对不健康文化的人,因为害怕失去未来获得基金的机会,选择了沉默;其他希望有所改变的人们则持“等待和观望”的态度,而不愿承担改革可能失败的风险。

尽管路途障碍重重,科学政策制定者和一线科学家们都已清楚地意识到中国目前科研文化中的问题。它浪费资源、腐蚀精神、阻碍创新。借助于研究经费增长的态势和日益强烈的打破有害成规的意愿,现在正是中国建设健康科研文化的时刻。一个简单但重要的起点是基于学术优劣,而不是靠关系,来分配所有的新基金。随着时间的流逝,这种新文化能够而且应该成为一种新系统的顶梁柱,它将培育而不再浪费中国的创新潜力。

原文:

Science 3 September 2010:

Vol. 329. no. 5996, p.1128.

DOI: 10.1126/science.1196916.

EDITORIAL:

China’s Research Culture

Yigong Shi 1,* and Yi Rao 2,

1 Yigong Shi is a professor and dean of the School of Life Sciences at Tsinghua University, Beijing, China.

2 Yi Rao is a professor and dean of the School of Life Sciences at Peking University, Beijing, China.

* E-mail: shi-lab@tsinghua.edu.cn.

E-mail: yrao@pku.edu.cn.

Government research funds in China have been growing at an annual rate of more than 20%, exceeding even the expectations of China’s most enthusiastic scientists. In theory, this could allow China to make truly outstanding progress in science and research, complementing the nation’s economic success. In reality, however, rampant problems in research funding—some attributable to the system and others cultural—are slowing down China’s potential pace of innovation.

Although scientific merit may still be the key to the success of smaller research grants, such as those from China’s National Natural Science Foundation, it is much less relevant for the megaproject grants from various government funding agencies, which range from tens to hundreds of millions of Chinese yuan (7 yuan equals approximately 1 U.S. dollar). For the latter, the key is the application guidelines that are issued each year to specify research areas and projects. Their ostensible purpose is to outline “national needs.” But the guidelines are often so narrowly described that they leave little doubt that the “needs” are anything but national; instead, the intended recipients are obvious. Committees appointed by bureaucrats in the funding agencies determine these annual guidelines. For obvious reasons, the chairs of the committees often listen to and usually cooperate with the bureaucrats. “Expert opinions” simply reflect a mutual understanding between a very small group of bureaucrats and their favorite scientists. This top-down approach stifles innovation and makes clear to everyone that the connections with bureaucrats and a few powerful scientists are paramount, dictating the entire process of guideline preparation. To obtain major grants in China, it is an open secret that doing good research is not as important as schmoozing with powerful bureaucrats and their favorite experts.

This problematic funding system is frequently ridiculed by the majority of Chinese researchers. And yet it is also, paradoxically, accepted by most of them. Some believe that there is no choice but to accept these conventions. This culture even permeates the minds of those who are new returnees from abroad; they quickly adapt to the local environment and perpetuate the unhealthy culture. A significant proportion of researchers in China spend too much time on building connections and not enough time attending seminars, discussing science, doing research, or training students (instead, using them as laborers in their laboratories). Most are too busy to be found in their own institutions. Some become part of the problem: They use connections to judge grant applicants and undervalue scientific merit.

There is no need to spell out the ethical code for scientific research and grants management, as most of the power brokers in Chinese research were educated in industrialized countries. But overhauling the system will be no easy task. Those favored by the existing system resist meaningful reform. Some who oppose the unhealthy culture choose to be silent for fear of losing future grant opportunities. Others who want change take the attitude of “wait and see,” rather than risk a losing battle.

Despite the roadblocks, those shaping science policy and those working at the bench clearly recognize the problems with China’s current research culture: It wastes resources, corrupts the spirit, and stymies innovation. The time for China to build a healthy research culture is now, riding the momentum of increasing funding and a growing strong will to break away from damaging conventions. A simple but important start would be to distribute all of the new funds based on merit, without regard to connections. Over time, this new culture could and should become the major pillar of a system that nurtures, rather than squanders, the innovative potential of China.

.png)