Law is not a shield

来自China Digital Space

fǎlǜ bú shì dǎngjiànpái 法律不是挡箭牌

Excuse used by a Chinese government spokesperson to defend authorities' treatment of foreign reporters.

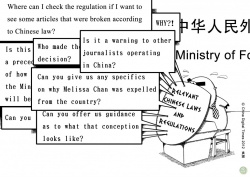

In early 2011, foreign journalists attempting to cover short-lived Jasmine Revolution protests in China were roughed up by police. At a press conference, journalists asked which law they had violated. Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Jiang Yu’s reply went down in Chinese Internet history. The exchange, as translated by Human Rights in China:

Question: Can you clearly tell us the specific clause of Chinese law that we have violated?

你能明确告诉我们违反了中国哪项法律的哪个条款吗?

Answer: The violation is of relevant regulations regarding the need for an application when going places to interview people. Don’t use the law as a shield. The real problem is that there are people who want to see the world in chaos. They want to make trouble in China. For people with these kinds of motives, I think no law can protect them. I hope everyone will sensibly recognize this problem. If you truly are reporters, then you should behave in accordance with the journalists’ professional standards. While in China you should respect China’s laws and regulations. Looking at the past two situations, those journalists who were waiting for something to happen did not get the news they expected. If during those two days there were people who incited and instigated you to go somewhere for an illegal assembly, I suggest that you promptly report that to the police, in order to, one, protect Beijing’s law and order, and two, protect your own safety, rights, and benefits.

违反了去那个地方采访需申请的有关规定。不要拿 法律当挡箭牌。问题的实质是有人唯恐天下不乱,想在中国闹事。对於抱有这种动机的人,我想什么法律也保护不了他。希望大家能够明智地认识这个问题。如果你 们是真正的记者,就应按照记者的职业准则行事,在中国要遵守中国的法律法规。从前两次情况看,那些去蹲守的记者也没有等到他们想等的新闻。如果这两天还有 人煽动、鼓动 你们再去什么地方非法聚集,建议你们及时报警,一是为了维护北京的治安,二是为了维护你们自身的安全和权益。[Source]

Jiang’s comments were extremely controversial, leaving many netizens asking, “If ‘the law is not a shield,’ what’s the point of the law?” (“法律不是挡箭牌”还要法律干什么) Among the most notable responses to Jiang Yu's comments was Attorney Chen Youxi's editorial in Southern Weekly (translated by China Media Project):

During the “Cultural Revolution” there was nothing left of the law, and this caused the entire nation to slide into civil strife. Injustice prevailed everywhere, and even the chairman of the republic (Liu Shaoqi) could not be protected. To a large extent it was in drawing lessons from this tragedy that our past 30 years of opening and reform have been not just 30 years of economic reform, but also 30 years of rapid development in building a legal system.

“The law is not a shield” is perhaps just a momentary slip of the tongue, but it gives the impression that China’s legal system is little more than a slogan or an accessory, something that can be used when it suits the purpose. When the government requires the law, the law can serve as a set of mandatory rules the population must respect; when it seems the law restrains one’s hand, it can be set aside. It’s as though the law is one-directional, serving to check the population but not to check power. If the law comes to be used as a tool, then clearly it is seen as something without sacred importance and not deserving of reverence—just as something utilitarian. [Source]

This turn of phrase has also been related to more recent events, such as the expulsion from China of Al-Jazeera reporter Melissa Chan in 2012.