Sun Zhigang

来自China Digital Space

Sūn Zhìgāng| 孙志刚

Sun Zhigang (1976-2003) was a college graduate who was beaten to death in police custody in Guangzhou. The fallout from his death fundamentally changed China’s labor, media, and legal rights movements and helped to spark the influential weiquan (rights defense) movement.

On the evening of March 17, 2003, local Guangzhou police arrested Sun, a Hubei native and recent college graduate working in the city, for failing to produce a required registration permit. He was taken to a custody and repatriation Center, a detention facility where those without the proper hukou (household registration permit) were held in anticipation of deportation to their registered address. Three days later, he was dead.

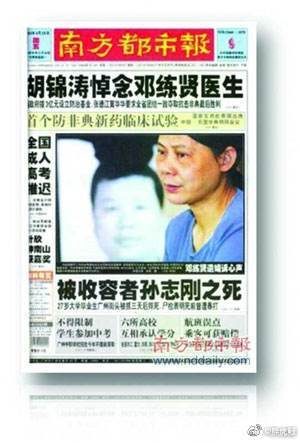

Sun's family went to Guangzhou to learn his cause of death, which officials declined to give. So the family turned to the pioneering Southern Metropolis Daily, a newspaper distinguished for for its taboo-breaking journalism. Journalists at the paper quickly discovered an autopsy report that disclosed Sun had been beaten to death. Cheng Yizhong, a Southern Metropolis Daily editor, decided to publish the muckracking report knowing full well it would incite the ire of authorities. The paper's coverage set Chinese society ablaze. Six police officers were eventually sentenced to prison, as was a nurse at the clinic where Sun was treated after his beating.

After the publication of the Southern Metropolis Daily report, three Peking University Ph.D.s, Xu Zhiyong, Teng Biao, and Yu Jiang, wrote an extraordinary open letter to the National People’s Congress calling for the abolition of the custody and repatriation centers. The government acquiesced to societal pressure and announced the closure of all 800 centers around the country. Eva Pils, an expert on the weiquan movement, has said that the Sun Zhigang incident inspired “this notion that perhaps rights defense could mean a bold group of courageous lawyers, legal professionals, and legal academics sympathizing with them, persuading the State to introduce incremental reforms.” China Central Television bestowed Teng and Xu with a “Ten People in Rule of Law in 2003” award for their activism.

Yet the following year, nearly the entire executive staff of Southern Metropolis Daily was arrested. The arrests, ostensibly on corruption charges, were official retaliation for the paper’s reporting on Sun Zhigang and SARS. Xu Zhiyong, one of the “Three Ph.D.s” of open letter fame, mounted an aggressive public defense of the papers staff replete with conferences, websites, and petition campaigns. Cheng Yizhong was held in jail for four months. Upon his release from, he gave a speech thanking the politicians who arrested him: “If it were not for your recklessness and stupidity, I would not have gained this honor and even more innocents would be swept in broad-sweeping similar cases.”

Sun’s death is still a sensitive topic. On the 10-year anniversary of his death, the Central Propaganda Department ordered media outlets to ignore his relatives’ tomb sacrifices. China Labour Bulletin argues that “the lives of young migrant workers have improved over the last decade… young workers have much greater freedom to seek work without having to worry about police harassment,” a freedom precipitated by Sun’s death. Xu Zhiyong and Teng Biao went on to lead China’s weiquan movement for over a decade, before crackdowns shattered the movement.