Such are the political and economic realities of China’s lethal coal mining business that all too often it doesn’t pay to play it clean. Sadly, the same can be said for journalism on the subject.

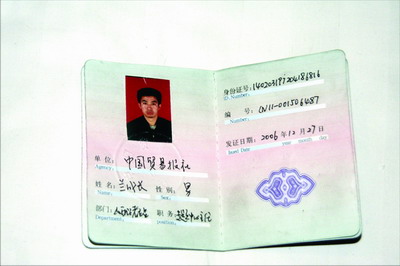

Celebrated reporter Wang Keqin confirmed this for himself in the mining town of Datong in recent days. On Wednesday, the China Economic Times carried Wang’s dispatch about the death of Lan Chengzhang, the China Trade News reporter battered by mine bosses from whom he apparently tried to extort hush money. As noted in an earlier post, ESWN’s Roland Soong has translated the whole of Wang’s published account, and aptly terms it the most extensive thus far. Wang illuminates the oligarchic ways of “black mine” owners in Shanxi, who burn their mother lode on stretch Hummers and high-end condos in the Beijing’s Central Business District. He also fleshes out why it would seem untenable for the government to define a “real” journalist as someone who holds a journalist’s permit, given the majority are currently unaccredited – even at official provincial and central outlets. Finally, Wang runs down the cast of corrupt reporters in China today, including a little-noticed breed of snitches and consigliere who engage in “public relations crisis management”.

But that’s still not whole the story, Wang asserted over the phone on Wednesday afternoon just after he got back to Beijing. His paper had to scratch some his juiciest findings, he said, particularly details about the business practices of papers in Datong. “Why was Lan Chengzhang extorting? Because his paper was doing so! Why was the paper doing so? Because that was their easiest way of making money! That’s the core of the problem: this dirty business.”

“Originally I felt the report would be very incisive,” Wang lamented. “But now I feel it’s not so powerful.”

The full story may yet be forthcoming. Meantime, herewith a 10-minute one-on-one with Wang Keqin:

Biganzi: You say the China Trade News played a role in Lan Changzheng’s actions?

Wang Keqin: Yes, the paper’s whole business model was problematic.

Biganzi: So you don’t think Lan’s is much of a case of the need to guarantee the rights of media oversight (ËàÜËÆ∫ÁõëÁù£)?

Wang: No, no, no, no, no. In order to safeguard the image of journalists conducting media oversight, we should punish these dirty, fake reporters. In the name of media oversight, they are obscuring or exaggerating the facts. To the contrary, they are damaging the image of media oversight. They are not doing the work that media oversight should be doing in Chinese society.

Biganzi: If the truth of the matter ultimately does more to damage the image of the watchdog media than highlight the dangers they face, then why couldn’t the China Economic Times publish your original piece?

Wang: Umm media to media relations. I think you understand my meaning. (laughs)

Biganzi: You’re not directly related, though.

Wang: Although we’re not one work unit, nor are we parent-subsidiary relations, we’re still colleagues. Colleagues remain bound by a sort of intangible alliance.

Biganzi: And you’re both linked to central government organizations?

Wang: Even if this was a local paper, there are times when it’s not easy to speak out.

Biganzi: In the version you have published, what breakthroughs do you think you achieved?

Wang: In what was published, the circumstances of the “dirty mines” as well as the savagery of the beatings are described very thoroughly. There’s an in-depth explanation of the problem of corruption in the media at present. But the problems with the news bureau(s) and the basic reasons for corruption are not sufficiently explained.

Biganzi: What’s happening with Meng Runli [a.k.a. Meng Er, the Datong-based Legal Daily reporter who police say advised the mine owner as to how to deal with Lan]?

Wang: Let me tell you, this guy is a extremely bad guy. He’s helping illegal businesses by doing illegitimate public relations, and thus providing them protection to act even more unscrupulously by breaking the law and violating discipline. This hurts the interests of the public.

Biganzi: Collusion between mafia and media is a scary prospect.

Wang: It’s extremely scary. When an accident happens at a mine, he [Meng] tells them: “To People’s Daily you give however much money, to Economic Daily you give however much, to Guangming Daily you give however much, to Shanxi Daily you give however much. That’s what he’s doing. It’s horrible!

Biganzi: Can you elaborate?

Wang: Based on the different media, the differences in status and different journalists, he helps you give them payoffs to send them away, so they don’t talk.

Biganzi: You hint at this in the published report but don’t go into detail.

Wang: Originally I did. But I only touched on it lightly, because I didn’t have more direct evidence. I didn’t investigate further, so I couldn’t write too much about it. Because behind [Meng] there’s the Legal Daily. The Legal Daily is one of the bigger media in China. [Wang goes on to talk about the Legal Daily. We’ve omitted his comments due to legal concerns]

Biganzi: The police circular named Meng as an informant for the mine. Did this surprise you?

Wang: No. The situation with the Legal Daily is all too normal. For this kind of situation to arise in China is normal. Meng was mentioned in the circular because he’s a key player. He gave testimony as to whether Lan Chengzhang was a “fake” reporter or a “real” one [i.e. whether Lan was officially accredited]. Without this person Meng Er, perhaps this mafia company wouldn’t have beaten Lan Chengzhang to death.

Biganzi: So what will happen to Meng?

Wang: [grunts] Don’t know. Up to this point, he hasn’t been arrested. As to how the police will assess his crimes, or his problems, I don’t know.

Biganzi: But you knew about Meng before the police circular named him?

Wang: Yeah. Within the local media, anybody with the slightest conscience, a lot of people, particularly hate him.

Biganzi: He’s well-known?

Wang: He’s drives a luxury [automobile] worth more 400,000 RMB. I don’t know what brand. He leads a very nice life. [Pauses]. Where does his money come from? Could he make all that money by writing news? Aren’t I writing news too? I can’t make money. I can’t buy a house.

Biganzi: He’s not an ordinary reporter?

Wang: Uhhh..he’s some sort of “chief” Ժ৥ÁõÆ, alternately, ‘ringleader’Ôºâ. I don’t know what position he holds.

Biganzi: How’d you find out about him?

Wang: Some local reporters divulged this to me.

Biganzi: How open was Datong to visiting domestic reporters?

Wang: The conditions were pretty good. No one [in the city government] really obstructed us.

Biganzi: Did people ask to see accreditations?

Wang: When I went to some other work units to interview, not only did they ask for my press card but also for my work permit and a permit for my mission (Ê¥æÈÅ£ËØÅ). When I heard that..[chuckles] it’s absurd. What do you mean, permit for my mission?

Biganzi: What did they mean?

Wang: Your work unit has to draft a letter of introduction for you to interview. Absurd.

Biganzi: Where did they ask for that?

Wang: When I was in the county where the incident occurred.

Biganzi: But things weren’t so strict in the city of Datong?

Wang: It was looser in Datong. But in Datong, a lot of media, a lot work units do believe that if you’re reporter, first they have to check your press card, then check your work permit, and then check your permit for the mission. So in future Chinese journalists in Shanxi, in Datong, will be reporting under this extremely sketchy state of affairs. That’s partly a consequence of the case of Lan Chengzhang.

Biganzi: It took the China Trade News quite a few days to straighten out its position on Lan’s activities. First, the paper stood behind him to an extent, confirming he was an employee. Later the paper made it starkly clear that he was not sent to the mine. Why the hesitation?

Wang: Yeah, that’s because of the paper’s problems.

Stay tuned.