Not to be suppressed, acclaimed journalist Wang Keqin has blogged unprinted portions of his probe into the death of reporter Lan Chengzhang. With the author’s permission, CDT’s Mo Ming translates them below.

Lan died at the hands of illegal coal mine bosses whom reports indicate he was trying to blackmail. Wang’s missing passages, now posted on his Sohu.com blog along with photos he shot in Shanxi, bring full circle his authoritative account of the controversial case. On January 24, the China Economic Times, Wang’s paper, published a version of it that ran over 13,000 characters long (translated in full on ESWN). But lopped off Wang’s piece were the two concluding sections, which illuminates how and why state-owned news media are tempted to sell out their watchdog services to their subjects. Critics may note that Wang focuses on the ethical and structural conflicts of interest that corrupt news journalists in China, leaving aside ever-implicit political stresses of censorship and the lack of legal protection. It’s important to realize, though, that Wang wrote the passages with the intention of publishing them in his paper. The China Economic Times, published by the Development Research Center of the State Council, nixed the passages anyway, primarily out of concern they would further tarnish fellow members of the industry, Wang explained in an earlier interview with Biganzi. No doubt, they will now.

The other parts of the piece posted on Wang’s blog include a few dramatic details that were edited out of the paper. For instance:

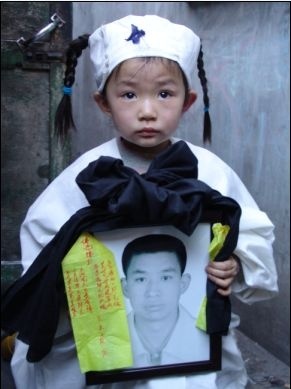

When Lan’s 4-year old little daughter Lu Lu saw the swelled and deformed head of her father, she remarked, “That’s not my father.” At Lan Chengzhang’s home, the reporter saw Lu Lu wearing her white mourning dress [pictured, as photographed by Wang]. At times she would cry along with her mother, while at other moments, she bounced and darted about.

The final graph of the version that ran was also meant to finish on a more damning note:

Friends in the area told the reporter that even some mine bosses possess press cards, and all are the press cards of central-level media.

A translation of the missing sections follows:

What on earth do news bureaus do?

“What on earth do news bureaus do?”

One resident of Datong posed this question to the reporter.

The “Measures for the Administration of Periodical Offices and Correspondents’ Stations” issued by China’s General Administration of Press and Publication, which took effect on March 1, 2005, offer the following definition: news bureaus conduct news operations such as interviews, writings, and correspondence (ÈÄöËÅî) according to the law and within the scope of their newspapers’ operations.

“That is to say, news bureaus are the inter-regional satellite bodies of newspapers that conduct purely news operations. They are in fact the media’s organizations in the field for editing and interviewing. News bureaus can only engage themselves in interviews and reporting, and are not allowed to engage in business, advertising, and circulation,” an authoritative source explains.

So what is the situation at China Trade News’ Shanxi Bureau, where Lan Chengzhang worked?

According to persons familiar with the situation, the Shanxi bureau currently has five people.

The former bureau chief who just left her post said in an interview with Southern Weekend:

“There are not many big companies in Shanxi, and the government departments are more willing to do publicity in newspapers such as Shanxi Daily,” said Li Ping, who worked as the China Trade News’ Shanxi bureau chief for 11 years. “Although coal mining companies are rich, they cannot dig up enough coal to meet the demand in the market. They don’t need publicity.” Li retired in December, 2006.

Li Ping said she once wrote stories about a certain companies with whom she had relatively good relations, and by doing this she could pull in five to six pages of advertisements a year. The advertising revenue on one page is about 9,000 yuan. Seventy percent of it goes to the newspaper, and 30 percent to the reporter as commission. The news bureau had sole responsibility for its profits or losses. Fortunately, we didn’t have to pay for our office as it was in the building of the Council for the Promotion of Trade. And the monthly telephone and fax bill was only about 100 kuai.

However, not all of those people who are reported in the newspaper are willing to pay for it. During the provincial legislative sessions in 2006, Li Ping interviewed a People’s Congress representative from Mianshan who was a coal mine owner. The story was accompanied by a large-size photo. After that, every time she sought out the mining boss in hope of pulling in a sponsorship, she was stopped outside the door by his secretary. The case was the same with the chairman of another coal mining company in Changzhi.

“Prior to 2005, the news bureau had it pretty good. For three years running, the newspaper named our bureau outstanding,” Li said. “But since headquarters imposed targets on reporters, our days became harder and harder. In 2005 our target was 50,000 yuan; in 2006 it went up to 100,000.”

A friend of Lan Chengzhang told the reporter that Lan once told him: “The news bureau hired me, and allocated me a revenue target of 180,000 yuan.” According to a senior reporter in Shanxi, the commission from this type of advertisements could be as high as 30 percent.

When the reporter interviewed the newspaper’s manager who is in charge of the news bureaus, he said, “We have not assigned any our news bureaus any business duties. We once did, but not now. The news bureaus are purely working on news reporting.”

“If they are purely news reporting organizations, then why don’t they hire university journalism graduates? So many students cannot find a job, yet they hire junior and senior high school students as their bureau chiefs?” questioned one young reporter with a local newspaper in Datong asked.

Chang Hanwen, the reporter who went to the illegal coal mine with Lan Chengzhang, was also a victim in this case. Chang’s position is “Director of the English Editorial Center at China Trade News Shanxi Bureau”. Chang, a 51-year old “senior comrade”, holds only a junior middle school degree.

With regard to this, a person in charge at the newspaper explained that the files from the bureaus show Chang has a junior college degree.

The reporter noticed that material publicized on the China Trade News website shows the newspaper has 29 bureaus around the country. The reporter noticed that the Gansu bureau has 30 people. Among them, one is the bureau chief, three are vice chiefs, and 26 are reporters. The Fujian bureau has three offices in Fuzhou, Xiamen, and Quanzhou. It also has six editorial centers in Zhangzhou and other cities. The Hainan bureau’s website shows that six people in the bureau are all “officials”. They are the bureau chief, the executive vice chief, the vice chief, the office director, the news center director, and the director of project and finance.

The reporter had a second interview with the person in charge of managing the news bureaus regarding operational costs and reporters’ salaries at the respective bureaus of the China Trade News. The manager told the reporter: “The newspaper gives every reporter an annual subsidy of 50,000 yuan. The salaries of the staff at the bureaus are paid by headquarters. The bureau chief’s monthly salary is normally 2,000-plus kuai, the average salary of the vice chief and other reporters is about 1,800 yuan, and other editorial costs are also paid by headquarters.”

The reporter added up the costs. The China Trade News has 29 bureaus nationally, so its expenditure on subsidies alone is nearly 1.5 million. Just to pay the salaries of bureau chiefs and reporters, to take as one example the Gansu bureau, where there are 26 reporters and four chiefs or vice chiefs, the expenditure for a year is more than 600,000.

What’s even more surprising to local reporters in Datong is that the “news worker credential” China Trade News issued to Lan Chengchang was strikingly similar to the official “news reporter credential” issued by the Administration of Press and Publication. Both have navy-blue leather jackets, and the covers of both are embossed with a bright silver emblem of the People’s Republic of China. The only difference is that one cover reads “news worker credential” and the other cover reads “news reporter credential”. Both are in English and Chinese. The pattern designs on the inside cover are virtually the same. On the “reporter credential” there is a big red seal of “General Administration of Press and Publication of People’s Republic of China”, while on the “worker credential” there’s the big red seal of the “China Trade News”. The rest is basically similar. One young reporter took out his journalist’s credential, compared it with Lan’s, and said, “The fake could totally be confused with the real thing!”

Zhan Jiang: News bureau corruption is systemic corruption

In regard to this, the reporter did a special interview with Professor Zhan Jiang (±ïʱü), Director of the Journalism Department at China Youth University for Political Sciences [in Beijing]. Zhan believes that the problem of the news bureaus in Chinese news world is extremely serious, to the extent that last year, four reporters were arrested in succession for blackmail. Wang Qiming (ʱ™ÂêØÊòé), the former China Food Quality News (‰∏≠ÂõΩÈ£üÂìÅË¥®ÈáèÊä•) Sichuan bureau vice-chief, was arrested on charges of blackmailing Jingyan Food Company (‰∫ïÁ†îÈ£üÂìÅÂÖ¨Âè∏) for hundreds of thousands of yuan; Meng Huaihu (Â≠üÊÄÄËôé), the former China Economic Times (‰∏≠ÂçéÂ∑•ÂïÜÊó∂Êä•) Zhejiang bureau chief, was arrested on charges of blackmailing Zhejiang Petrochemical Corporation (ʵôʱüÁúÅÁü≥Ê≤πÊĪÂÖ¨Âè∏) for 350,000 yuan; Bu Jun (ÂçúÂÜõ), former vice chief of the Zhejiang bureau of the Economic Daily’s rural edition (ÁªèʵéÊó•Êä•ÂÜúÊùëÁâà), was arrested on charges of blackmailing ordinary citizens for 58,000 yuan; and Chen Jinliang (ÈôàÈáëËâØ), former executive vice chief at the Henan Bureau of the China Industrial News (‰∏≠ÂõΩÂ∑•‰∏öÊä•), was arrested on charges of blackmailing the Construction Bureau of Guangshan County, Henan province, for 20,000 yuan.

In fact, to China’s press insiders, the problem is not so complicated. Indeed, changing economic and social conditions in recent years have whet the desires of some in the media community for “rent seeking”. However, the root causes of corruption in the news world are supervisory and systemic flaws exposed by the market economy. News bureaus around the country have come to epitomize the flaws.

Public institutions, business operations

Starting in the 1980s, the China news media began to undergo a transition, from institutions directly owned and run by the government (政府包办的直属单位) to public institutions run as businesses (实行企业化运作的事业单位). The market economy has brought the media tremendous economic benefits and certain space for news operation. At the same time, it has allowed the government to cast off the heavy burden of financial responsibility. So there was a time when it seemed there would emerge a win-win situation for the media and the government. Media supervisors and some media researchers were endlessly excited and jumped for joy.

However, the good times didn’t last for long. Due to the media’s special political identity and the de facto monopoly status of the industry, the old system of the Party media (ÂÖöÊä•) did not have a system design to curb rent seeking. Therefore, a type of internal corruption developed. First, reporters used the excuse of “positive publicity” to win the good graces of their subjects, then proceeded to sell them advertisements without a hitch. The media obtained the bulk of the advertisement revenue, and reporters pocketed the rest as “commissions (ÁªÑÁ®øË¥π)”. This invention of the Chinese media in the 1980s was actually a kickback. It was an early form of “paid news”.

At the same time, a form that looked both like a news story and a commercial promotion known as “advertising literature” (nowadays nicknamed “soft news”) came into print as “special editions”. This not only benefited media enthusiasts, but also brought wealth to some unsuccessful local writers.

In outset of the 1990s, taking “red envelopes” at “news conferences” became a new type of “paid news”. One reporter from a certain Beijing newspaper set a record of attending 26 “press conferences” in a month.

But overall, the media advertising market was gradually changed from a “seller’s market” in the 1980’s to a “buyer’s market” in the 1990’s. The situation was even more so for national newspapers. Therefore, “news rent seeking” became more expensive and difficult. This may explain why in recent years, there were many cases of news blackmailing in the name of watchdog journalism (ËàÜËÆ∫ÁõëÁù£).

„ÄÄ„ÄÄ

After the path of dependence

Management of the local bureaus of national newspapers is laxer than at headquarters.

In the 1980’s, most of the correspondents from major newspapers were assigned from the paper’s ministerial clique of personnel. Some of them swore they would never change, while others exploited the “sellers’ market” to get rich off of advertisements, to the extent that they might receive awards from the newspapers for their outstanding achievements in advertising.

In other words, from the early days of “public institutions with business operations”, one of the main missions of the news bureaus was “digging up new revenue sources” for headquarters. Under the banner of news reporting or even watchdog journalism, a considerable number of reporters cleverly pocket or even extort money. One reason is that their ethics and legal bottom line do not match up with those of professional reporters. The root of this is “revenue benchmarks” and “reward and punishment mechanisms” that the headquarters employ.

Back when the author was working at a local newspaper [the Gansu Economic Daily in Lanzhou], a manager at a company run by the paper was detained for over a year on the charge of embezzling 4,000 yuan. After learning of this, an advertising staffer at the local bureau of a major Beijing newspaper (who had a reporter credential, as many of them do) commented matter-of-factly: “If I were at your newspaper, I would be executed.” As far as the author knows, he and several of his friends among the advertising staff of the bureau each owned more than one apartment in Beijing in the 1990s.

In the past several years, under the pressures of a buyer’s advertising market, some news bureaus have started hiring local “hotshots” (less influential media started this process much earlier). Their main duty is peddling advertisement and writing “commercial literature”. Their performance is evaluated not so much on the basis of news writing as on the basis of running a business.

Using theories of Institutional Economics, it’s not hard to explain this phenomenon: once a person makes a choice, it’s something like taking a road with no return. Force of habit will constantly reinforce this choice, and leave you unable to make an easy exit. This is so-called “path dependence”. That’s because economic life, like the physical world, has a mechanism of increasing returns and a mechanism of self-reinforcement.

Path dependence can take different directions. In one scenario, once an initial system is decided upon, it has the effect of progressively increasing the returns and promoting economic development; additional institutions are oriented in a corresponding direction, which leads to further systemic change in favor of economic development. This is a benign form of path dependence. In another scenario, after the evolutionary track of a certain institution is shaped, the efficiency of the initial system decreases. The system even begins to impede production.

Organizations sharing a common prosperity with the institution make every effort to protect their own interests. This is a malignant form of path dependence.

This cannot but force us to reflect upon the model of “public institutions with business operations”. In this regard, He Zengke, a political scholar the Contemporary Marxism Research Center at the Central Bureau of Compilation and Translation, writes incisively in his book New Road of Fighting Corruption „ÄäÂèçËÖêÊñ∞Ë∑Ø„Äã: “Public institutions such as press and publications, broadcasting, and television are both government-owned and commercialized. This system is the root of all unhealthy practices in the field.”

What is conventional behavior?

Corruption in the press also exists in other nations in the midst of transition. For example, it’s common for reporters in Russia to accept “red envelopes”; and in Mexico, some reporters receive cash in their mail boxes every week. The reality shows that defects in China’s media institutions (designed or natural) have reached such an extent that time has come to deepen reforms. The author believes that a coexistence of press professionalism with market mechanisms, that is, a separation of news operations and business operations, is the fundamental solution.

Last year, the General Administration of Press and Publication (GAPP), together with the Discipline Inspection Department of the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection within GAPP, co-hosted a special meeting on the supervision of news bureaus of central institution-owned newspapers. In response to the problems at news bureaus, the meeting ordered central institution-owned newspapers to launch a full-scale campaign of self-inspection and self-correction based on the laws, regulations and policies such as “Regulation on the Administration of Publications”, “Provisions on the Administration of Newspaper Publication”, “Measures for the Administration of Periodical Offices and Correspondents’ Stations “, “Measures for the Administration of Press Credentials”, and “Provisional Regulation on the Administration of News and Editorial Staff”. The meeting ordered central institution-owned newspapers to inspect one by one their internal supervision systems as well as the supervision of news bureaus in different areas. In particular, it ordered newspapers to inspect as to “whether newspapers impose circulation and advertising tasks on reporters, and whether news bureaus illegally engage in business activities.”

It appears that supervisory departments have not only recognized the seriousness of the problems, but also have found suitable countermeasures. Still, the worry is that if the internal mechanisms of the press, specifically the mechanisms of business operations and news operations, cannot be effectively separated, it will be hard for this form of self-inspection to create a stable system. Instead the winds of false formalism will blow in and out. It would seem likely that the “red envelope” phenomenon will not stop but rather will grow. And demanding the media change its current operations model seems an even harder mission.