70 years ago this week, the U.S. repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act, a law that had prohibited all immigration of Chinese laborers since 1882. Despite the discriminatory policy, many Chinese continued to enter the U.S. on forged papers, and a report from NPR looks at the genealogical confusion that still lingers today:

William Wong says that even as a child, he knew Wong was his last name on paper only; his real family name is Gee.

“We knew when we were growing up in Oakland’s Chinatown that we were a Gee family,” says Wong, 72, a retired journalist in Piedmont, Calif.

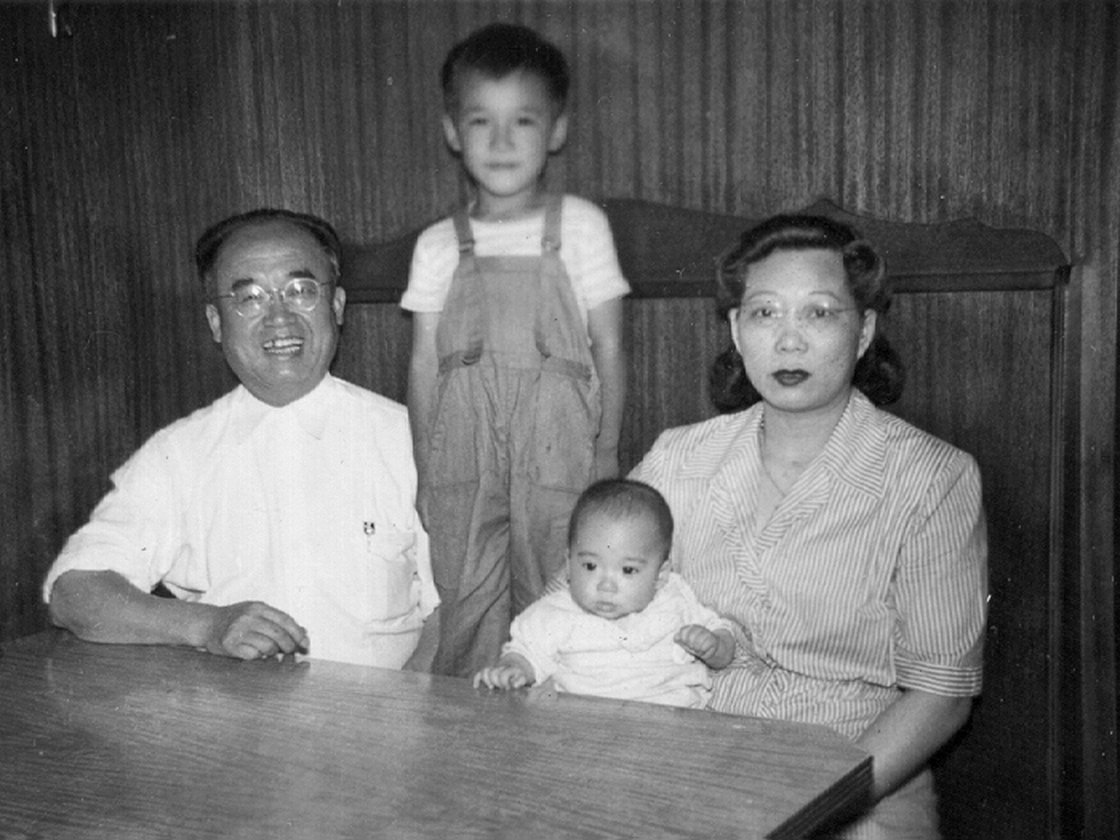

Wong’s family was one of thousands made up of “paper sons and daughters,” Chinese immigrants who were the “children” of Chinese-American citizens only on paper — fraudulent documents with false names. Blood relatives of American-born Chinese, as well as Chinese merchants, teachers and students, were among the exceptions to the immigration restrictions, which targeted Chinese laborers.

[…] Decades after the Chinese Exclusion Act has settled into history books, many of the descendants of paper sons and daughters are still trying to learn the truth. [Source]

70 years after the repeal of the Chinese Exclusion Act, Asian-Americans in Florida are pressing state lawmakers to scrap a standing (if unenforced) provision preventing Asians from owning property in the state.

For more on “paper sons and daughters,” see Byron Yee’s one-man show “Paper Son” or Felicia Lowe’s upcoming documentary “Chinese Couplets”—Yee and Lowe were both featured in the NPR story. For Canadian examples of ancestral ambiguity as a result of immigration policy, watch the short film “Paper Sons and Daughters” on Vimeo. Also see The New York Times’ coverage of a new immigration study which tells a modern day Chinese immigration story.