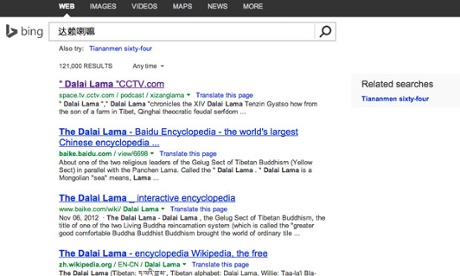

Following accusations that Microsoft internationally censored politically sensitive content on its search engine Bing, and Microsoft’s subsequent denial, Jason Q. Ng at The Wall Street Journal considers whether the censorship on Bing was intentional.

Though GreatFire published two follow-up posts clearly refuting some of Microsoft’s claims in this latest case, the underlying assertion that Microsoft tinkered with its international search engine in order to ingratiate itself with Chinese authorities feels somewhat implausible. China has little to gain in pressuring Microsoft to censor the international version of Bing — a search engine not much used by Chinese people in or outside of the country. Nor does it seem likely that Microsoft would be willing to take such a controversial step with its flagship online brand, whether voluntarily or under Chinese pressure. Importantly, Chinese search results on Bing for a number of obviously sensitive terms like “六四事件” (June 4 Incident) appear not to have been adjusted, calling into doubt the existence of deliberate censorship.

A more plausible explanation is that, due to the numerous local laws and jurisdictions Microsoft has to account for, an honest mistake was made (which doesn’t excuse the company: they still wrote and implemented whatever code was at fault here). As popular Chinese mobile messaging app WeChat demonstrated with its own international censorship fiasco last year, filtering algorithms have a way of showing up in places they weren’t intended to be.

[…] While it remains unclear why Microsoft shrugged off GreatFire’s initial overtures, it’s possible the group’s reputation among tech companies as more firebrand than potential partner may have had something to do with it. In any case, Microsoft still has a chance to turn GreatFire’s allegations to its advantage by using this controversy as a chance to address more openly the challenges it faces in places like China. Opening a dialogue about its social responsibilities, while embracing the ability of activists to help make its products better, would do more to burnish the company’s reputation than any fix to their algorithm can. [Source]

At the Guardian, Rebecca MacKinnon similarly writes that “I don’t believe that Microsoft intended” to censor, “but the company is by no means off the hook.”

After conducting my own research, running my own tests, and drawing upon nearly a decade of experience studying Chinese internet censorship, I have concluded that what several activists and journalists have described as censorship on Bing is actually what one might call “second hand censorship”. Basically, Microsoft failed to consider the consequences of blindly applying apolitical mathematical algorithms to politically manipulated and censored web content.

[…] The algorithm deployed by Bing may be mathematically sound, but it fails to protect online freedom of expression. Bing failed to take into account the political reality of Chinese government censorship and its broader impact on the shape of the Chinese internet. Without adjustments to how simplified Chinese websites based outside of mainland China are “weighted,” exiled and dissident online voices inevitably lose out. Put it another way: an apolitical mathematical formula automatically amplifies Chinese government censorship to all people searching for simplified Chinese content anywhere in the world, not just in China. [Source]