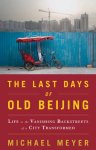

Beijing-based writer Josh Chin contributed the following review of Michael Meyer’s “The Last Days of Old Beijing: Life in the Vanishing Backstreets of a City Transformed,” to CDT:

,” due out from Walker and Company this month. How much is there to be gained in listening to yet another requiem for a place that never seems to die?

The answer, in Meyer’s case, is plenty.

An award-winning travel writer, Meyer has done what few other foreign residents in Beijing are willing to do: actually live in the hutong. It’s true, many Westerners rent courtyard houses, but theirs are the neo-imperial mini-palaces of New Beijing, cleared of riff-raff, retrofitted with radiators and equipped with sit-down toilets. Meyer’s perch in the neglected lanes south of Tiananmen Square is not so luxurious. For heat in winter, he relies on cups of Nescafe and the bowls of dumplings foisted on him by the Widow, his busy-bodied old neighbor. The dumplings and instant coffee processed, he walks across the lane to the public latrine, where one of his students once bowed to him as he squatted, pants around ankles, over the open trough.

The result is an account of life in the hutong rich with lived detail but blessedly absent the romanticism and sentimentality that afflict so much of the expatriate lane literature. At times, there is a postcard quality to Meyer’s descriptions: “Grandmothers push prams filled with vegetables from Heavenly Peach market. The bells of black steel Flying Pigeon Bicycles warn to make way…” But these passages read more like an anxious ledger of scenes soon to be lost than a poem to the exotic, and are few at any rate. Instead, Meyer builds the book around portraits of his neighbors: the Widow, chain-smoking matron of the courtyard; Recycler Wang, who envies the tin buyer at Trash Village; Teacher Zhu, who has put pregnancy on hold until she knows when her school will be demolished.

One of the most memorable of the characters in “Last Days” appears early on, as Meyer describes the character 拆 (chai, demolish) painted on the walls of a neighbor’s home: “Mr. Yang had never seen someone paint the symbol, and neither had I. It just appeared overnight, like a gang tag, or the work of a specter. The Hand.” Dispatched at the behest of a mysterious cabal of government officials and real estate developers, The Hand terrorizes nearly everyone Meyer meets.

Sadly, “Last Days” never manages to uncover the mechanism behind The Hand. It does, however, rely on Chinese historical sources (most of them new to Western readers) to draw up an enlightening sketch of Beijing’s transformation from a close-knit, teeming maze of lanes named for the products or services offered in their shops (Chrysanthemum Lane, West Grindstone Lane), into an inhuman grid of wider-than-wide avenues dominated by immense structures designed to be admired rather than lived in—what Zhang Yonghe, an architect Meyer interviews, calls a “City of Objects.”

One of the contributions of “Last Days” is to place this transformation in its proper context. Paris was also erased and redrawn, Meyer reminds us, as were major parts of Moscow, New York City, and Athens. In the end, Meyer and his neighbors are preservationists, but it’s not the architecture they care most about. Instead, it’s the refuge the lanes provide, the space they provide for humanity and civility in a city that grows colder and harder by the year. Meyer makes this point with particular force when he describes the numerous kidnapping stories he and his neighbors read in the local newspaper. “None of the missing had disappeared from a hutong,” he writes. “Rather, they vanished from wide roads, high-rise complexes and bus stops. Erasing a city’s urban corners left only straight lines, hollow spaces and nowhere to hide.”

Beijing will probably always have its hutong and courtyard houses, which are rare enough now to have considerable real estate value. But the atmosphere of Old Beijing—the life—is already fast seeping out of them. In Michael Meyer, we are fortunate to have a writer with the clarity, humor and depth to capture that life before it flows away completely.