As notoriously smoggy cities and a rising yuan seem to be discouraging inbound tourism to mainland China, members of China’s emerging middle class are beginning to spend their increasingly valuable travel money outside of the PRC—nearly 100 million Chinese tourists left China last year, and by 2020 that number is projected to double. Ahead of a “Golden Week” expected to break outbound tourism records in China, CDT conducted an email interview with a young woman who exemplifies a new type of Chinese tourist: young, wanderlusty, and willing to abandon the guided tour for a more adventurous itinerary.

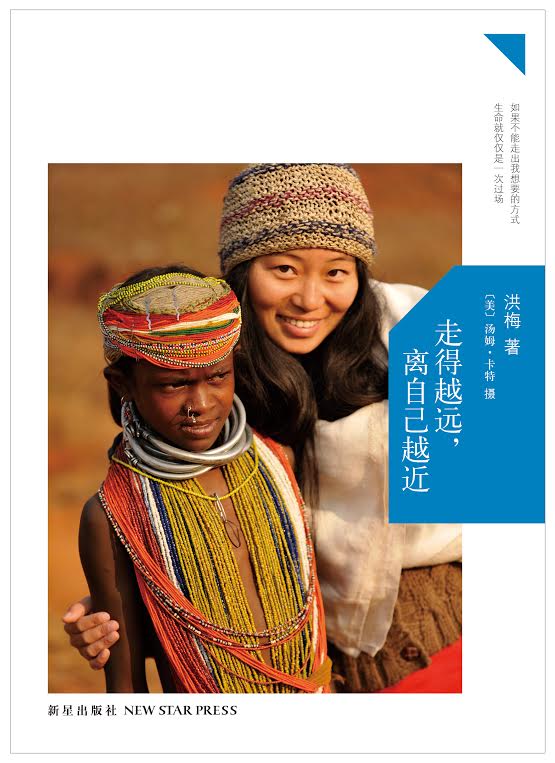

Hong Mei (洪梅) recently published the Chinese-language travelogue The Farther I Walk, the Closer I Get to Me (走得越远,离自己越近), detailing her yearlong backpacking trip across India.

China Digital Times: Tell us a bit about your educational and professional background.

Hong Mei: My background won’t impress anyone. I come from a small village in the rural Jiangsu. My family are tea growers. When I was 19 years old I made the great leap to Beijing, like so many young people from China’s countryside do. In Beijing I taught myself English. I took a Self Taught Higher Education Examination, which for many 80’s generation youth was a popular alternative to the national examination and attending university. My professional background is even less impressive: after receiving my degree, I was a bit directionless, so I just took a job as a secretary for a language school. But it is where I met my future husband, Tom Carter, so I guess it means being directionless was my destiny.

CDT: Can you pinpoint the reasons that inspired you to head to India?

HM: The reasons go all the way back to meeting Tom in Beijing in 2005. His intention was to go backpacking alone across China’s 33 provinces. When he returned to Beijing a year later, he was offered a publishing deal to turn all his photographs from that journey into a book. He’s not a professional photographer, but he’s a perfectionist, so he wanted to spend another year photographing China all over again. He convinced me to quit my job and come with him. Not comfortable travel, but hard budget backpacking: living on just a few dollars a day, sleeping on bus station floors, sometimes not taking baths for a week… It was the first time I had traveled anywhere. It opened my eyes to my own country’s people and culture. The result of that trip was Tom’s first book, CHINA: Portrait of a People, which compelled Tom to pursue travel photography seriously, and made me want to see the world.

CDT: Why India? How long did you spend on the Subcontinent? What was your route?

HM: We talked about it and realized that India offered the challenges that we backpackers thrive on, and a vast geography where we could lose ourselves for a year. As a photographer, Tom sought a populous that was as diverse as China. There are over 2,000 ethnic groups in India, including 600 scheduled tribes (what we call “ethnic minorities” in China, which we only have 56 of). And there’s no national language in India; over 700 languages spoken there. We were aware that India offered everything we were seeking as backpackers and photography, yet we didn’t actually know anything about India. We were unaware of its cultural complexities, and just how hard traveling in India for a year would be. The plan was to spend at least a year there, or until our money ran out. No route either. For Tom and me, our travels are kind of like our lives: directionless.

CDT: Did you encounter curiosities about India among your peers in China growing up? What reactions did you get from friends and family when you told them your plans to travel there?

HM: This was the second job I’d be quitting to travel for a year. In the West you call it “gap year”. And I think it illustrates something that is occurring more and more here in China: young Chinese who, for the first time in several generations, now have the opportunity and the means to travel the world. We are educated, our economy is strong, but there’s little incentive for us to devote the best years of our lives to the meaningless jobs that corporate China offers us. Why not go travel for a year and experience life? Yet gap years and backpacking are still seen as being irresponsible by the older generation of Chinese. But was it irresponsible for me to quit work to go learn about the world? Or is it irresponsible of a society to not do more to educate its people about the world?

CDT: Did you encounter curiosity about China from Indian locals? If people you met had preconceived notions about China and Chinese people, were they accurate?

HM: There’s a small community of Chinese who long ago migrated to Calcutta and made their homes there, but even they never travel anywhere in India. Western, and even Japanese and Korean, backpackers can be found wandering all over India, but my fellow Chinese dare not. “Konichiwa! Annyeonghaseyo!” The Indian locals would always shout out at me. “I’m Chinese,” I’d say. “We’ve never seen a Chinese before,” they’d say. Some would pull out their China Mobile phone and smile, others would do a little song and dance from a popular Bollywood gongfu comedy called Chandni Chowk to China. But that’s the extent of Indian laobaixing’s notions of China. Faxian and Xuanzang might have been the first Chinese to travel to India, but sometimes it felt like I was the first.

CDT: India and China offer a tempting comparison to the outside observer: the world’s two fastest-growing large economies and biggest countries by population have both experienced massive growth in recent decades, are both racked by inequality, and are the two countries most associated with the burgeoning “Asian Century.” The two also depart significantly in certain realms—most relevant to this website would be in the presence/lack of representative democracy and press freedom. Could you offer some reflection on similarities and differences between the two countries as you encountered them on your travels?

HM: This was my very first ever trip abroad, but in many ways my travels across China had subconsciously prepared me for India: two traditional societies facing accelerated economic upturn. Both countries have the potential to become – or should I say re-emerge – as dominant leaders in global economic and political relations. To quote a passage from a funny novel by Aravind Adiga titled White Tiger: “The future of the world lays with the yellow man and the brown man now that the white man has wasted himself on cell phones and drugs.” The major differences being that India actually cherishes its history, whereas China seems to be doing everything to obliterate its past for the sake of becoming a global superpower.

CDT: Often, when one spends significant time abroad, projected expectations of the host country are shattered. How did you imagine India prior to your arrival? How did your expectations compare to the India you found?

HM: I had no expectations. The most profound thing I didn’t expect from my travels in India came at the realization that I was in the world’s largest democracy. Westerners tend to take democracy and freedom of speech for granted, but for me it was impressive to see people in India doing things that here in China would get them disappeared. In Delhi I saw a protest by sugarcane workers, thousands of laobaixing shut down the streets of their nation’s capital to assert their rights. And I was in Mumbai on Election Day 2009; watching all the campaigns and candidates was very exciting for me, even though I kept looking over my shoulder like I was doing something wrong by being there. I event went to Southern Orissa, the heartland of India’s Naxalite rebellion. The Naxal-Maoist insurgency, inspired Mao Zedong’s People’s War, has been active in India for the past decade defending the rights of marginalized peoples. Which is ironic because here in China the CCP is doing everything to vanquish its farmers and peasants. Our driver in Orissa was nervous to take us because I am Chinese and there was a rumor saying Maoist weapons were bought from China. These incidences are NOT in my book, however. My publisher had to censor them out.

CDT: What did you learn about China from your time in India?

HM: You know, I’m just a village girl, so my observations about India and China are not very deep. For me, I took a simple delight in just sitting all day on the ghats of spiritual centers like Varanasi to just watch humanity pass by. And many of these Indian laobaixing have very little possessions, yet they have spirituality and faith. And that’s when I reflected that we Chinese have sacrificed our souls and our happiness for materialism. We have lost all our spirituality. We have no faith, and no morals, to guide us. We don’t even have our traditions anymore. We Chinese as a people have become as directionless as these two backpackers are.

CDT: Based on a recent Pew survey, the majority of Chinese don’t hold a very favorable view of their geopolitical neighbor to the southwest. As China’s emerging middle class begin to spend more abroad, India seems to so far be missing out. In years to come, do you think it’s likely many of them will choose India as a vacation destination? If not, what are some things that could help in attracting Chinese tourists?

HM: As someone not involved in politics or journalism or business, just another laobaixing, I can’t say I agree with any surveys that say we Chinese don’t hold favorable views of other countries. It’s not that we collectively have an unfavorable view of Japan, for example. It’s that our state-run media pounds it into our subconscious all day long with ceaseless anti-Japanese television shows and news broadcasts, along with the occasional government-endorsed anti-Japanese riot. But India is different – we don’t have ANY view of India. We are simply oblivious of India. For most of us, it’s just a country that existed long ago in fables like Journey to the West. But Xi Jinping’s recent visit with Indian Prime Minister Modi last week was a kind of eye-opening event for us. Suddenly, we have a neighbor to the west, and it’s called Yìndù. Xi’s announcement that China will invest billions in India’s railway was also a groundbreaking triumph in Sino-Indian relations. There’s no doubt that this will lead to granting Favored Nation Status to India, which is going to result in a surge of bilateral tourism and trade between both countries. Based on the new reports about the bad behavior of Chinese tourists in other countries, I’m not sure India is ready for an influx of Chinese tourism, so I should apologize in advance on behalf of my fellow Chinese who will carve their names into the Taj Mahal.