As China marks the 50th anniversary of the launch of the Cultural Revolution, many writers and commentators have noted the lack of public discussion and accountability for the violence and destruction of the decade that followed. Writer Yan Lianke, whose book “The Four Books” has been short-listed for a Man Booker prize, was recently interviewed by Catherine Wong of the South China Morning Post:

“There is never enough discussion about the Cultural Revolution,” Yan said recently in Hong Kong, where is a guest lecturer of Chinese literature for six months at the city’s University of Science and Technology.

“The more we talk about it and the more critical are our reflections on it, the more China will progress for the better. But China will go backwards if we keep avoiding the subject.”

According to Yan, what conversation there is on the Cultural Revolution mirrors how the country’s intellectuals confront history.

“We will have to resume the discussion about Cultural Revolution sooner or later, to understand its problems,” he said. [Source]

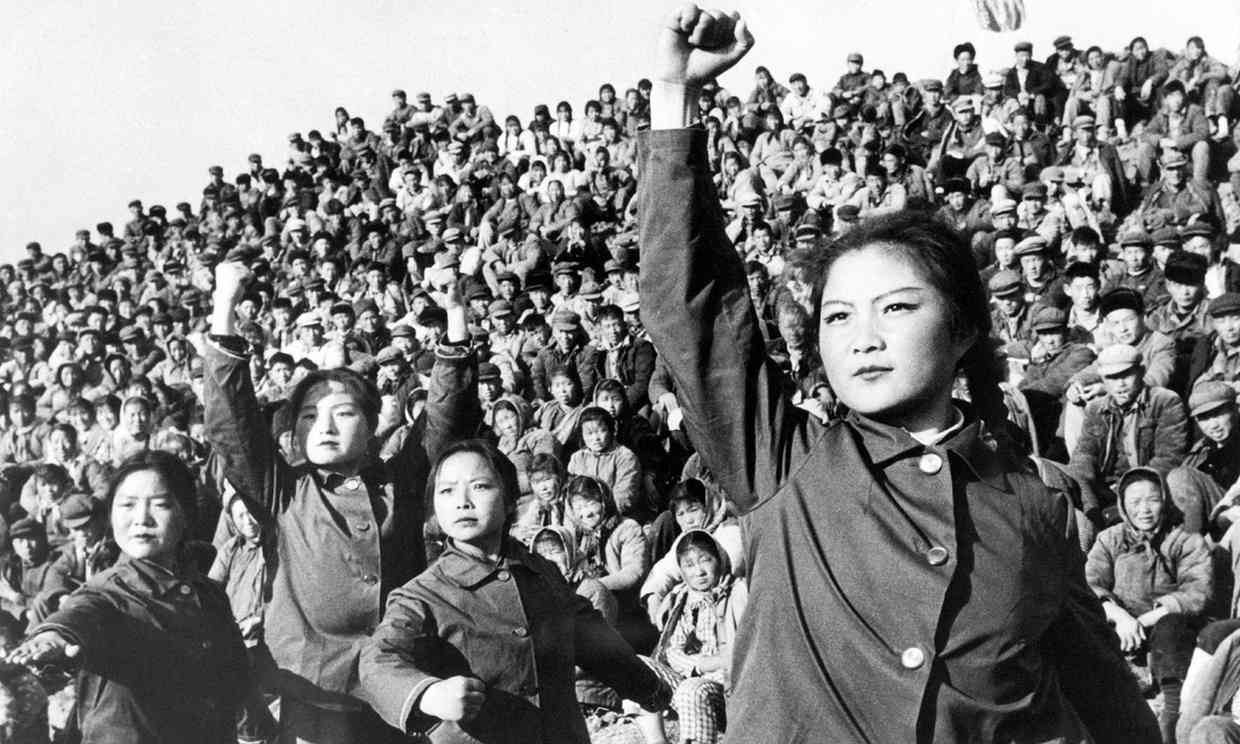

Yu Xiangzhen, who was a 13-year-old schoolgirl when Mao Zedong launched the Cultural Revolution, has contributed to the discussion by blogging about her own experiences as a Red Guard. By Tom Phillips at The Guardian:

[…S]ince the start of this year, Yu has been trying to use her blog to tear down the wall of official silence surrounding the events of that bloody summer.

“If our descendants do not know the truth they will make the same mistakes again,” she wrote in the introduction to her series of online reflections. “I want to use real experiences to prove that the Cultural Revolution was inhumane.”

Even half a century on, Yu, a retired journalist, says she is still trying to fathom the horrors she witnessed that summer and to understand how she was radicalised into becoming one of Mao’s “little generals”.

[…] Yu’s reflections on those days of chaos have earned praise from many readers. “People who stand up to tell the truth are so rare these days,” one fan wrote on her blog. “So we look forward to more people like Teacher Yu coming out to tell the truth. I really appreciate what Teacher Yu has done.” [Source]

As Professor Yiju Huang of Fordham University tells Nicholas Taggerty in Commonweal, the government’s failure to allow people to mourn has left lingering “ghosts” in Chinese society that are preventing any real closure on the events of the decade between 1966-1976:

Nicholas Haggerty: What’s the standard view of the Cultural Revolution in China?

Yiju Huang: In China, the Cultural Revolution is understood as a decade of chaos, but also there was a hasty attempt to bring a sense of closure. Although Mao’s image was tarnished, his legacy is also salvaged—‘he was misguided by the scapegoat figures of the ‘Gang of Four,’ but now that the dust has settled, we can move forward.’

From my perspective, however, there still linger a number of ghosts. The crimes that were committed in the utopian name of the greater good have not been properly worked through.

[…] NH: Do you think there is any legacy that can be salvaged?

YH: That’s a really hard question. We should certainly engage with the legacies—the multiple and often contending meanings—of the Cultural Revolution from theoretical, historical, political and psychological perspectives.

[…] In my view, the work of mourning should come first before one can begin to imagine the revival of an emancipatory legacy. In other words, you have to—to invoke Derrida here—introduce a psychoanalytic element to the political realm. [Source]

Tomas Plänkers, a psychoanalyst at the Sigmund Freud Institute in Frankfurt, has researched the psychological impact of the Cultural Revolution on Chinese society and compares the situation to that in Germany after World War II. Didi Kirsten Tatlow interviews him in The New York Times about his findings:

Q. What is your experience discussing this in China?

A. Cultures have intensive denial mechanisms to deal with such things, something we also know from Germany. Fortunately in Germany today we have a very vigorous intellectual culture and can say what we want in order to resist this affective moment of denial. But the culture of the critical intellectual is not very vigorous in China. And that has to do with the political situation. Such commentary is unwelcome. Under such conditions people think three times about saying anything.

Q. What about Chinese psychologists?

A. In Shanghai last year I talked to about 200 Chinese mental health professionals about the Mitscherlichs’ book [Alexander and Margarete Mitscherlich, “The Inability to Mourn: Principles of Collective Behavior”] about Germany’s experiences with trauma after World War II.

I only talked about Germany, but afterwards there was stormy discussion of the Chinese situation. It’s amazing to see the reactions even when the topic was only discussed indirectly. Many people were very critical about China’s media and politics. So I asked them, “Do you talk about this honestly in your own families?” And silence fell.

It’s very similar to us in Germany. Children didn’t ask their parents about their experiences during the Nazi time. They could feel that it was a difficult subject. I didn’t ask my father what he did in the army. But we should be asking, “Do you talk about it in your family? What do you know? Do you have questions?” [Source]

Read more about the Cultural Revolution, via CDT.

Correction: This post has been updated to correct the title of “The Four Books.”