Mengyu Dong is a freelance journalist and photographer based in Washington D.C. She is currently documenting the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement, focusing on the participation of a group of young Chinese and Asian protesters who are voicing their support for racial justice. For CDT, she has put together several of her photos of “Chinese for Black Lives” protesters, together with her interviews with the participants. She can be found on Twitter and Instagram. All photos below are taken by Mengyu Dong.

Chinese-Americans and Chinese nationals, the younger generation in particular, are showing solidarity with Black Lives Matter.

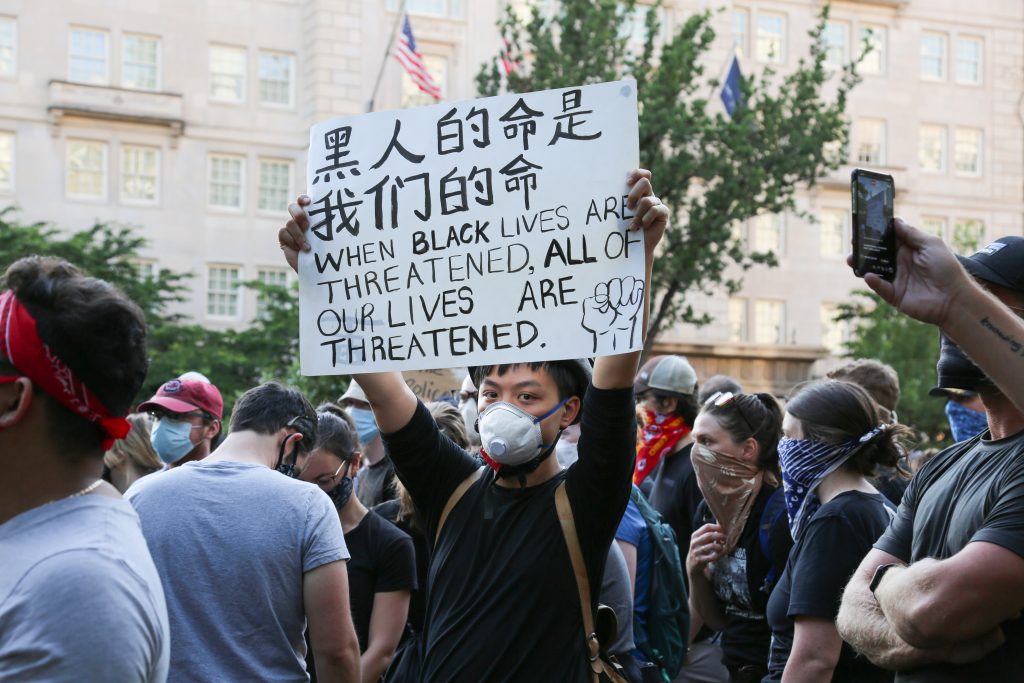

Jackie at a protest in front of the White House. Washington DC. June 2, 2020.

I first met Jackie in early June at a peaceful protest outside the White House. Among hundreds of protesters, his sign instantly captured my eyes. In big Chinese characters, he wrote: 黑人的命是我们的命 (“Black lives are our lives.”)

Jackie is a 24-year-old first generation Chinese immigrant. He said he had never experienced police violence himself. But seeing what happened to George Floyd, he could not keep silent. “When I see Black people losing their lives every day, I start to wonder what I believe in and what I can do,” he told me, “so I decided to do whatever I can by coming out here to fight for my ideals and those of my fellow Americans.”

He was excited to find out that he was not alone. Later that week, Jackie joined a WeChat group that consisted of dozens of Chinese students and professionals in America who support racial justice. They have been reaching out to Chinese business owners in their cities, asking them to display support for BLM. Starting in Manhattan, NY, the campaign has since expanded to Boston, Toronto, Vancouver, and many other cities in North America. When it came to D.C., Jackie immediately signed up.

Jackie in Chinatown, DC. June 27, 2020.

Jackie in Chinatown, DC. June 27, 2020.

On a hot and humid day in late June, Jackie went to D.C. Chinatown with a few new posters. There he met Ashley and Cuizi.

Cuizi, left, a second generation Chinese immigrant, is putting up a sign with Jackie, right. The sign says, in Chinese, “Black Lives Matter.”. June 27, 2020. Chinatown, Washington, DC.

Ashley, left, is putting up a sign with Cuizi, right. June 27, 2020, in Chinatown, Washington DC.

Ashley was born and raised in China. She came to D.C. in 2018 to pursue her graduate studies in international politics. Ashley is taking more risks than her U.S. citizen counterparts to participate in demonstrations: a single arrest can put her visa status in jeopardy.

One night she attended a protest outside the White House, which unexpectedly turned confrontational. “The police suddenly shot pepper balls at us,” Ashley tells me. “I am not a U.S. citizen. And the current U.S.-China relationship is terrible. I thought: what should I do if I get arrested?”

But she is motivated to come out and support BLM because she believes what happened to George Floyd “can happen to anyone.” “I want to speak up. I want to be part of the change,” says Ashley.

Cuizi is a second generation Chinese-American. Her parents came to America in the 1980s and she and her brother grew up here. From an early age, Cuizi felt a sense of being peripheral to American society. “It was hard for me to make sense of the feeling,” says Cuizi, “I think [it] is common for many Chinese and other Asian people in the U.S.” She found solace in reading W.E.B. DuBois, James Baldwin and other African American writers’ works. “I learned that my feeling of being at the margins of the American experience had a profound and humane lineage.”

Now working in D.C., Cuizi is taking an active role in mobilizing the Chinese community to support BLM. “To me, these conversations are a way of recognizing the dignity of Black people and Chinese people within a society that denies the full humanity of both groups,” says Cuizi, “I hope our conversations can lead to better understanding of ourselves and each other’s communities.”

An African-American resident of DC is talking to Cuizi and Jackie. She thanked them for the poster and asked to have one for her granddaughter. June 23 2020. Chinatown, Washington DC.

Ashley and Cuizi are putting up a poster that supports BLM in Chinatown, DC. June 27, 2020.

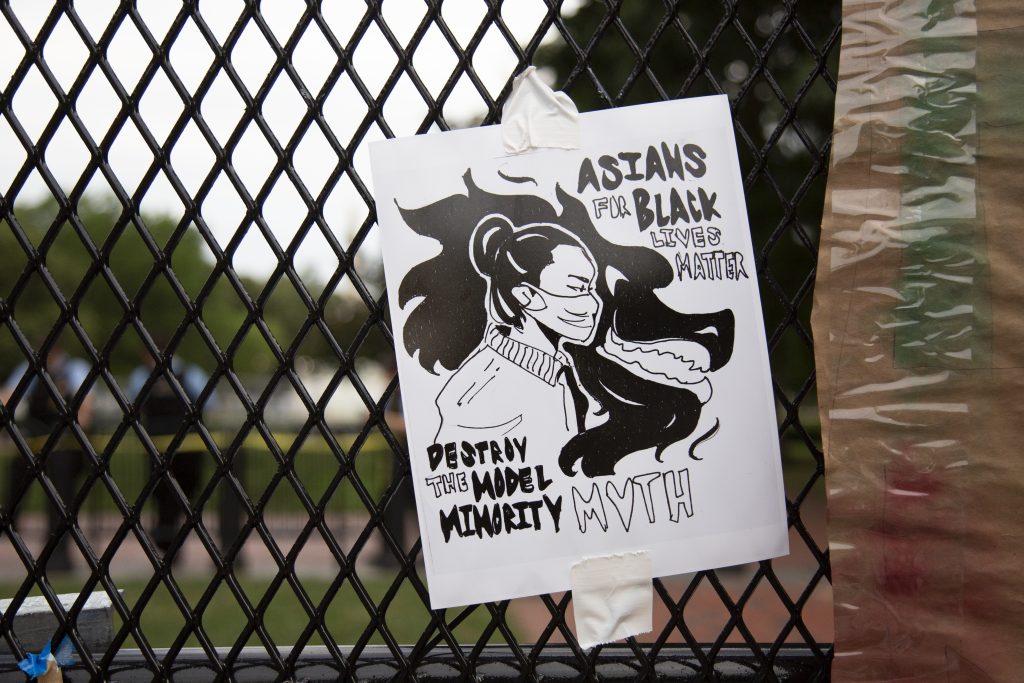

A poster in Chinatown DC that says “Asians for Black Lives.” June 27, 2020.

A sign hanging in front of the White House. June 28 2020.

Zoe, right, is attending a protest in front of the Capitol in Washington DC, with a friend, left. June 6, 2020.

Cuizi helped draft a bilingual statement for Chinese for Black Lives, in which she rejected the “model minority” stereotype as hurting both Chinese people and Black people. “[The] limiting portrayals of ‘good minorities’ blames Black people for not being able to overcome the disadvantages of systemic racism,” she wrote.

Zoe, a 24-year-old young professional in D.C., is one of the many Chinese-Americans who share these sentiments. Zoe visited Hong Kong, where her parents come from, last December. She saw thousands of protesters demanding that police be held accountable for their acts of violence. Despite the differences between the two movements, what she saw in Hong Kong made her feel guilty for not speaking up against injustices in America.

“I can’t justify my silence. I can’t justify my indecision and my inability to stand up for those in need even if I am not directly affected by their suffering,” she wrote after the death of George Floyd, blaming her “indecision” on the “model minority” identity that she had been ingrained with. “I need to take the same rage I have for the Hong Kong protest, towards the Black Lives Movement.”

The sign that Zoe carried to the protest says: “Black lives matter more than my image as a model minority. #yellowperilsupportsblackpower”

She said she felt “ashamed” after watching George Floyd suffocating under the weight of a white police officer, while an Asian police officer watched. She decided to come out and protest to let the Black community know that she stood with them as an Asian woman.

For some young Chinese immigrants, this is the very first protest they have ever attended. I saw this sign in front of the White House. It was hanging on the fence around the statue of President Andrew Jackson.

A bilingual sign that supports BLM is hanging in front of the statue of former US President Andrew Jackson near the White House. June 18, 2020.

我无法肤吸 (wǒ wú fǎ fū xī) is a slight twist of 我无法呼(hū)吸 which means “I can’t breathe.” The word 肤 means “skin” which adds to the context: I can’t breathe because of my skin.

I later found the young man who made this sign. He goes by the nickname Huhu. Born and raised in China, Huhu came to America a few years ago and became one of more than 400,000 Chinese students currently studying in the US. It was his first time going to a protest.

“In China, protests are seen as reactionary and meaningless,” said Huhu, who still felt uncomfortable about demonstrations after coming to America. “As much as I wanted to participate, I often gave up because I felt afraid and embarrassed.”

But seeing what happened to George Floyd, Huhu decided to step outside his comfort zone. He wanted to make a special sign for the first rally he attended—something that embodies his identities as both a racial minority and a member of the LGBTQ community.

“June happens to be Pride Month, so I used colored pencils to show support for the LGBTQ community, and of course, the last words of Floyd to show support for BLM,” Huhu told me.

Upon reading in the news about the scale of BLM demonstrations, Huhu was excited. “The first protest I attended in my whole life may be the largest in U.S. history,” he tweeted. “I feel like I am a part of history already.

A young woman holding a bilingual sign that says “Black Lives Matter!” in front of the White House, Washington DC. June 2, 2020.

There are many more people whom I didn’t have a chance to meet in person. One of them is Ceci, a 29-year-old Chinese national working in the Greater Los Angeles Area, who helped organize Asians for Black Lives events in her city.

“Minorities should not be pitted against each other,” Ceci told me over the phone. “Like Black people, Chinese people have also been racialized as ‘bad minority’ depending on the circumstances. Even now, we are sometimes seen as a model minority, a virus, or a spy.”

An Asian woman is holding up a sign that says “Yellow Peril Supports Black Power” near the White House. June 2 2020.

An Asian woman is holding up a sign that says “Asians for Black Lives” near the White House. June 6 2020.

Ceci became a U.S. permanent resident earlier this year, but her parents and extended family are all living in China. She admits that it’s been difficult to have conversations with family about racial justice.

Like many Chinese people in both China and the U.S., Ceci’s parents heavily rely on WeChat as their source of information. “There are so many blogs on WeChat that capitalize on racism and xenophobia.” She tried to report those articles to WeChat’s censors, but received no response.

She often chafes at WeChat’s censorship, but she never expected she’d one day be angry at WeChat for “not censoring enough.”

“If it’s a political rumor about China, it gets deleted instantly. But racism? They just don’t care,” Ceci laments. WeChat community guidelines do not explicitly ban racism or hate speech.

“So I think, well, if I can’t get rid of those racist articles online, maybe I should do something positive in the real world.” In early June, Ceci started a fundraising campaign online which raised more than $2000. She used the money to purchase food and beverages from local Black-owned businesses and made them available for protesters free of charge.

“I think what motivates me and many others to come out and show our support is a sense of solidarity,” says Ceci. “Because ultimately, a more just society, racially, politically and economically, is better for everyone.”

See also Talking Race with Chinese Parents by Chinese Storytellers and At the Margins of a Movement, Forging a Common Language from Sixth Tone, and visit Chinese for Black Lives on Twitter and Instagram.