“Reading and writing is what keeps me alive,” wrote prolific essayist Shen Maohua in his first piece back from a 15-day WeChat suspension. Shen, who writes under the pen name Wei Zhou, was temporarily booted from the platform after writing about 14-year-old diver Quan Hongchan’s record-shattering Olympic victory. In interviews, the young Olympian said she was driven by wanting to help pay for her mother’s medical bills. Visitors soon mobbed her rural hometown searching for the star and offering to help. In his typically rangy style, Shen examined the relationship between Olympic success, fame’s impact on family, and the limits of “Chineseness,” eventually concluding with a paraphrase of Lu Xun’s famous adage on medicine and the nation, “Diving can save mom, but it cannot save the Chinese people.” The piece earned him a 15-day ban, which in turn inspired his reflections on writers’ responsibility to write. At turns playful and solemn, in the essay below Shen concludes that it is impossible to tip-toe around the elephant in the room, thus he must risk bumping into it. Again like Lu Xun, Shen rejects the somnolency of the iron house in favor of writing on in the face of censorship. To his fans and his censor alike, Shen writes, “Believe me, I will always come back”:

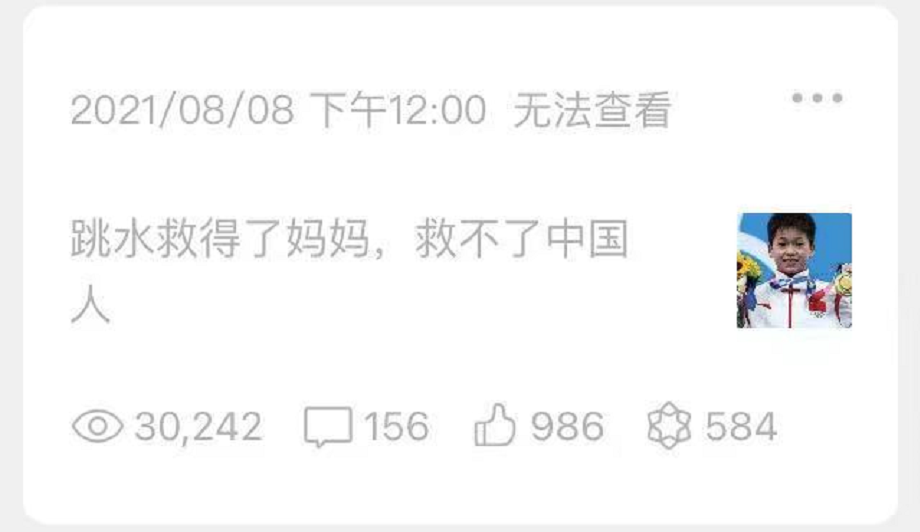

At 5:09 p.m. on August 8, while chatting with friends over tea, I got a notification from WeChat that my public account, “Wei Zhou,” had been banned for 15 days. The culprit was an essay I’d published that day, which had upset some readers.

“Diving can save mom, but it cannot save the Chinese people” [Read the original Chinese essay here]

30,000 people read the post during the five hours it was live.

I only know this because the person or people who reported me left messages on both my Douban account and my alternate account with less followers (I’m not sure if it was the same person). They disagreed with my argument and conclusion. This is all quite common. But out of a sense of righteousness, they struck back by reporting me. I’m left speechless by their shamelessness. What’s even harder to understand is: they’d already punished me by getting my account banned, yet they still pushed on to discover my alternate account to leave message after message (I can’t block people on my alternate account’s message board). What has possessed them?

I’m not new to having accounts muted or banned. I’ve experienced much. To tell the truth, my first reaction wasn’t rage. I just felt like it was pointless. It was only a different opinion. If you don’t want to read it, then don’t read it. The essay that led to my account getting shuttered has been reposted without edits on other accounts and is still sitting pretty.

Li Ling [a prominent historian] once said that some probe a question out of curiosity, in search of the joy of learning, while others do it in pursuit of victory, to eliminate all dissent:

When it comes to studying, I advocate for play. I’ll use athletics as an example. I prefer individual sports over team ones. I like competitive sports least of all. I believe that studying is a way to entertain oneself. To teach is to impart joy. If you don’t think of it as a high-brow profession, just treat it as a way to make a living, or to clear your mind and pass the time. All good, too.

The people I hate the most are like Wen Suchen from “Yesou Puyan” [a Qing-dynasty epic novel]. He didn’t like monks, so he vowed to kill each and every last one of them, all the way down into Southeast Asia. If people like Suchen want to purify all under heaven and go into academics, they can be terrifying. They “study without complaint” in order to “tirelessly destroy others.” They wipe out others on sight, under the impression that under all of heaven, only their corner of academia is academia, others’ work is not up to par. They think, “if you’re not a champion, get off the pitch.” This is called making a fool of yourself. They’ve made academia meaningless for themselves, and for everyone else. And so scholarship and humanity are both destroyed.

Of course he’s talking about academia, but lots of people defend their own opinions in similar ways, if not worse. Because to those rich in righteousness, it is not simply a divergence in perspective, but rather indicates one’s incorrect views on “cardinal truths.” This makes it even more impossible to reason with them, as it is no longer a question of “reason,” or at least not a “reason” that can be discussed.

To be honest, I did feel a bit of regret after my account was suspended. I’m well aware that the atmosphere is getting more suffocating by the day. At present it’s best not to use provocative titles like mine that invite people to give you trouble. Although this is slightly reminiscent of victim-blaming, akin to “women blaming themselves for being humiliated,” many people have told me that “carrying on with life is more important than anything else.”

No matter how careful, in an environment suffused with politics, it’s impossible to completely avoid the elephant in the room. It’s so big that it’s easy to bump into it just by turning around. Although some say, “In my 20 years on the internet I’ve never met another person as cultivated and genteel as Wei Zhou,” others say my criticism is already pretty “extreme.”

A friend told me, “They’re fighting about you on Douban.” The strange thing is some think, “The ones taunting Wei Zhou on Douban have the wrong politics,” while another group thinks the opposite. Although during my years online I’ve never cursed anyone out, I’ve been taunted and blocked quite a few times. Whether I care or not is neither here nor there, it’s just that spending any effort on the topic is too great a waste of energy. Over the past few years the feeling that I’ve not got the time to waste on such meaningless things has grown even stronger.

The public discourse is so cacophonous that it can create the misperception that it is nearly everything in life. But real life is much more vast. There is no need to brawl in a mud pit. I don’t even write to convince anyone. I just say what comes to mind. If some people think “it’s a little interesting,” that’s all there is to it.

After my public account was closed, my Douban account was muted for seven days for the same reason. During this time, I saw a dear friend of mine delete their account in despair. Two other friends were forced offline after stepping on red lines. Some say, “I feel that the Relevant Organs suspending an account is a mark of their affirmation. Could they at least present us with a banner when they ban our accounts? Then we wouldn’t have died in vain.”

A number of people wrote to Douban pleading their cases, as can be expected. But from the looks of it, I fear that the platforms have their hands tied. I’m afraid that those issuing the commands don’t know or care about the people they suspend, or how much time and effort they’ve spent creating. Finding the smallest of issues is enough. While watching “Journey to the West” as a little kid, I didn’t understand why Sandy was exiled simply for destroying a vase. Now I do.

I’ve seen that many people are already discouraged. A couple of days ago I saw a widely shared article titled “The Goodbyes Have Begun. Take Your Leave and Treasure the Memories.” That tone recalls English diplomat Sir Edward Grey’s famous words at the beginning of World War I: “The lamps are going out all over Europe, we shall not see them lit again in our life-time.”

My account has been suspended for 15 days twice in the last three months. Added together, I have been unable to speak for one third of that time. Over the past two weeks, I’ve been lucky that I can still speak out on my alternate account, even though two of my essays have been deleted within the last ten days. My alternate account is called, “Wei Zhou’s Ark.” Someone straight up told me, “The way I see it, your main account will be permanently banned sooner rather than later. You need an ark for your ark.”

To avoid losing contact, please follow this alternate account.

I once wrote, “If Zhang Wenhong Can No Longer Speak Out,” and wrote in the conclusion, “If someday he is no longer able to speak out, some will consider it a victory, but it will be a loss for all of us.” Some readers responded:

“I’m more afraid of when Wei Zhou can no longer speak out.”

“If Wei Zhou can no longer speak out, it will also be a loss for all of us.”

One reader told me, “I beg you to stop writing. Those who can understand what you’re writing will understand it forever. But those who don’t understand can’t understand, and they will never understand. Social discourse has really transformed.”

He’s not the only one thinking this way. Someone else spent even more effort trying to dissuade me from writing because she had personally seen terrifying consequences: “Someone as good-hearted as you has no reason to take such big risks.” Later, she became upset with me: “Those readers of yours, the ones supporting you as you barge ahead, I don’t think they’re good people. Mull it over! Bye!”

How should I put it? It’s not that I’m ignorant of my current position. I also know they all came to me in good faith. It’s just that now that I’m 40 years old, I’ve come to believe that the most important thing in life is staying true to yourself. Reading and writing is what keeps me alive. They are the essence of life. Of course I will be careful. But if I do not continue, then I will no longer be myself.

A couple of days ago, a reader told me, “No matter what happens, no matter where you end up writing, I will go there to read your work. As long as you keep writing, I’ll keep reading.” I thank her, and I thank all of those who’ve continued to follow along. Believe me, I will always come back. We will stand fast together. [Chinese]

For more of Shen’s work, read CDT’s recent translations of his essays on the ultra-marathon tragedy in Gansu, “empathy for authority” amid the Xinjiang cotton boycotts, and his examination of Chinese people’s two selves: the simultaneous national optimist and personal pessimist.