Chen Guangcheng’s recently-released memoir, “The Barefoot Lawyer: A Blind Man’s Fight for Justice and Freedom in China”, provides his account of his escape from house arrest in his Shandong village, his covert journey to Beijing, his stay at the U.S. Embassy there, and his subsequent trip to New York. For the Wall Street Journal’s China Real Time blog, Josh Chin interviews Chen about his experiences and his book:

You made it to Beijing, and after some negotiation and a car chase, you got it into the U.S. embassy. You write that once you arrived, the U.S. government kept changing its position. What kind of impact did that experience have on your view of the U.S.?

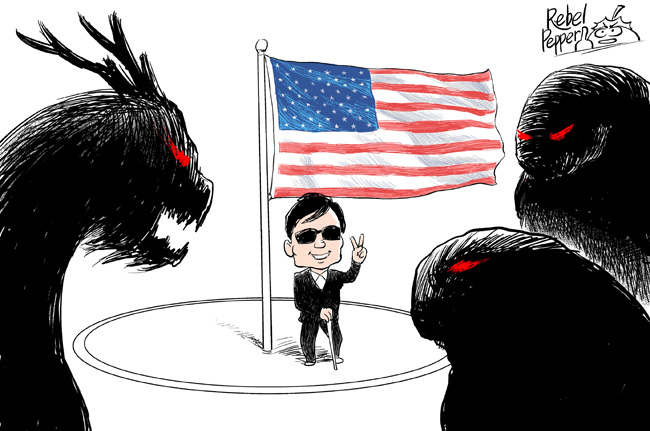

When I first got to the embassy, they were very, very good to me. You could tell the staff members were all excited. They thought they were doing something important and right. But not too long after I arrived, there was meeting, I think in the White House, and that’s when things started to change. After another meeting three days later, the situation completely switched and the new order was to get me out of the embassy as quickly as possible to avoid have a bad influence on relations with the Communist Party. Prior to that I believed deeply and without question in the U.S. as a defender of democracy and human rights. Of course, afterwards I realized politicians don’t always think from the standpoint of the people. But if you look around the world, even though the U.S. is sometimes weak in the face of dictators, it’s still the best defender of freedom there is.

[…] Now you’re in the U.S., which a very different place than rural Shandong. What has been the hardest thing to get used to?

The language. I didn’t have much time to study English in China. As for the other differences, the different customs or whatever, it’s not a big deal. When it comes to kindness or the pursuit of social justice, I actually don’t think Americans and Chinese people are very different. It’s just that Chinese people live in an authoritarian state and have been oppressed for too long, so they’re a little bit careful and afraid to speak out. [Source]

Also in the Wall Street Journal, lawyer Jerome Cohen, a close friend of Chen’s who participated in the negotiations after his arrival at the U.S. Embassy, writes his account of Chen’s stay there:

In his book, Mr. Chen says he felt enormous pressure to leave the embassy, despite his great fears that the Chinese government would not respect the compromise in practice. I can testify to those pressures and fears since I had extensive telephone conversations with him at the time.

The calls came about at Mr. Koh’s request as a way to allow Mr. Chen to discuss the situation with an American friend in whom he had expressed confidence. So on each of the two days before he left the embassy, I received briefings from Mr. Koh and Assistant Secretary of State Kurt Campbell, and then I talked with Mr. Chen.

On the first day we talked, after hearing Mr. Chen’s repeated fears, I advised him to stay in the embassy. Meanwhile U.S. diplomats were urging him to consider the anticipated drawbacks, including the State Department’s doubts about the legality of harboring him as well as the certainty of the Chinese government’s outrage.

After a second day of persuasion by U.S. diplomats, Mr. Chen was significantly less fearful and seemed willing to assume the risk of leaving the embassy. I urged him to ask that President Barack Obama personally issue a statement promising continuing concern for Mr. Chen’s security. Although no presidential statement was forthcoming, Secretary Clinton did offer her own assurance as she arrived in Beijing for the Security and Economic Dialogue. [Source]

Read review’s of Chen’s book via The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, and The Economist. Read more about Chen Guangcheng, via CDT.