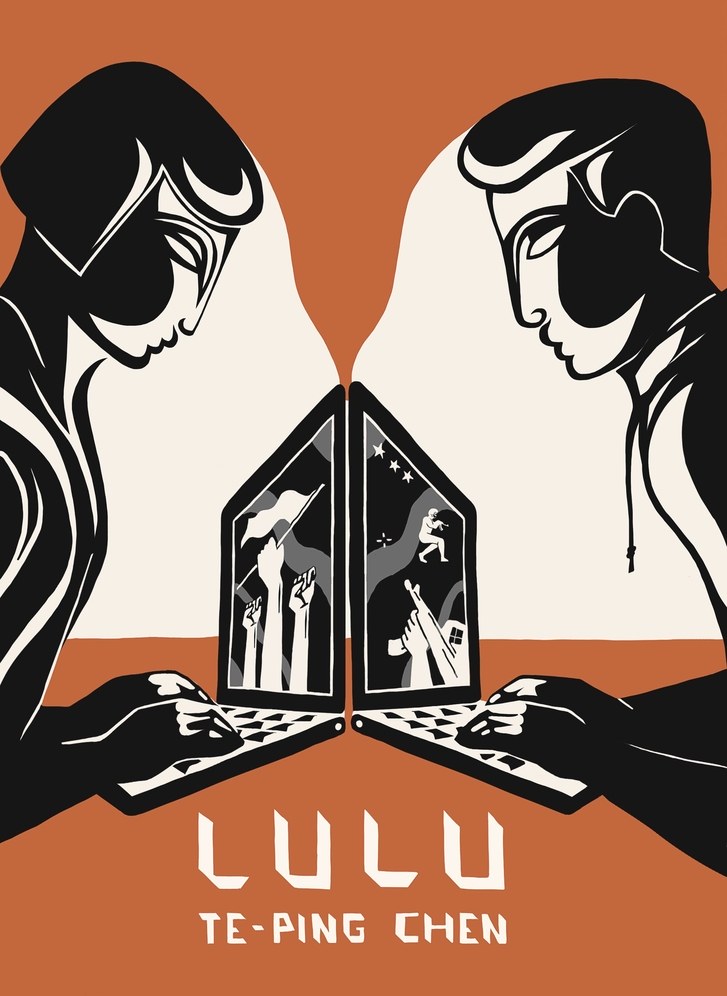

The New Yorker this week features a piece of short fiction by Te-Ping Chen, drawing on her time as a China correspondent for The Wall Street Journal. The story details a young woman’s emerging political activism through the remote eyes of her skeptical twin brother.

After that, Lulu’s account became more active. At first she was just reposting news from other accounts: the tainted-formula scandal that killed three babies, the college-admissions administrator found to be taking cash bribes—the kinds of things we all knew and groused about.

A few months after that, though, she began to flood her account with images and videos that were genuinely surprising. I had no idea where she was getting them. They were of scattered street protests from around the country, some just stills, others clips of perhaps a few seconds, rarely more than a minute long. Hubei, Luzhou city, Tianbei county, Mengshan village: 10 villagers protest outside government offices over death of local woman, one might say. Or: Shandong, Caiyang city, Taining county, Huaqi village: 500 workers strike for three days, protesting over unpaid wages.

There were dozens of these posts, and they usually looked similar: police in pale-blue shirts, lots of shouting, crowds massing in the streets, occasionally someone on the ground being beaten. In one video, several men were attempting to tip over a police van. In another, a group of villagers were shouting as something that looked horribly like a human figure smoldered on the ground.

They were like dispatches from a country I had never seen, and they disturbed and confused me.

[…] The most recent post was from that evening, just before we sat down to dinner. It was a line of text in quotation marks: “If you want to understand your own country, then you’ve already stepped on the path to criminality,” it read. And then: “Happy Spring Festival, comrades!” [Source]

Chen discussed the story with The New Yorker’s David Wallace:

In “Lulu,” your story in this week’s issue, a young Chinese man watches his twin sister become increasingly involved in dissident activism—her actions seem to leave him at a loss. Was there a specific idea behind the decision to narrate this story from the brother’s perspective?

There’s a certain duality of life in China (and in most places), in which you have very different realities that coexist. China is a place where people who are experiencing the worst of the state’s actions can live intimately alongside residents and visitors who are able to be much more apolitical, and who never really have to think about those on the other side. It’s a dichotomy that underpins so much of life there, one that’s hard to wrap your mind around. I wanted to write about this strangeness from the perspective of someone who would never think about the darker parts of society until a loved one forced him to.

[…] Something else that struck me is the critical role the Internet plays, from the reposting of censored videos to the narrator’s gaming life to his chats with his distant sister. The circulation of information and the role-playing fantasy seem to be almost in competition. Did you feel like you were working to bring these properties of the Internet, especially in China, more into focus in your story?

I think that’s right. Early on there’s a feeling of promise that’s represented in the father’s gift of identical laptops. But as the two siblings chart different courses through the Internet—one of entertainment and escape, the other of trying to better understand the world around her—in some ways their paths converge. They both know what it’s like to feel powerful online, and also, I suspect, that the experience is disposable. […] [Source]

Previously, at The Wall Street Journal last month, Chen described how she traced her own family in Beijing through a rediscovered collection of letters:

In the tumultuous years of the early 20th century, after China’s last imperial dynasty was overthrown, many Chinese hoped to build a new, democratic era. My great-grandfather—an outspoken poet who ran a newspaper that advocated passionately for the rights to free speech and a free press—was among them.

The Communist Party changed all that after it took power in 1949, splitting apart families and silencing those who disagreed with its path. Before then, I was able to find a long public record of my great-grandfather’s life and activities. Then he essentially vanished.

[…] My great-grandfather’s story is a poignant testimonial to paths not taken, offering a brief glimpse of a moment when China could have become a very different country. [Source]