Over 9 million Chinese high school students sat for Thursday’s National Higher Education Entrance Exam, or gaokao, where AFP’s Beh Lih Yi reports that intravenous drips, hormone injections, transmitters and ear pieces only spelled the beginning of the “drastic measures” students took to land one of the 6.85 million university spots up for grabs:

Some of the more affluent parents have rented houses close to the 7,300 exam venues across the country, while so-called “high-flyer rooms” are being offered in the northern port city of Tianjin, according to the state-run China Daily newspaper.

The special hotel rooms — which cost up to 800 yuan ($126) more than an ordinary room — are billed as having previously been rented out to someone who scored high points in the exams.

Rooms with lucky numbers such as six — which symbolises success in Chinese culture, or eight — which represents wealth — are also favourites.

…

The exam has also given rise to a new and lucrative industry — the gaokao baomu — or “exam nannies” — who are tasked to look after students during the exam period.

“The nannies are well-qualified with at least a college-level degree,” said Jennifer Liu, marketing manager at Coleclub — an agency that provides household help and has offered the service since 2009.

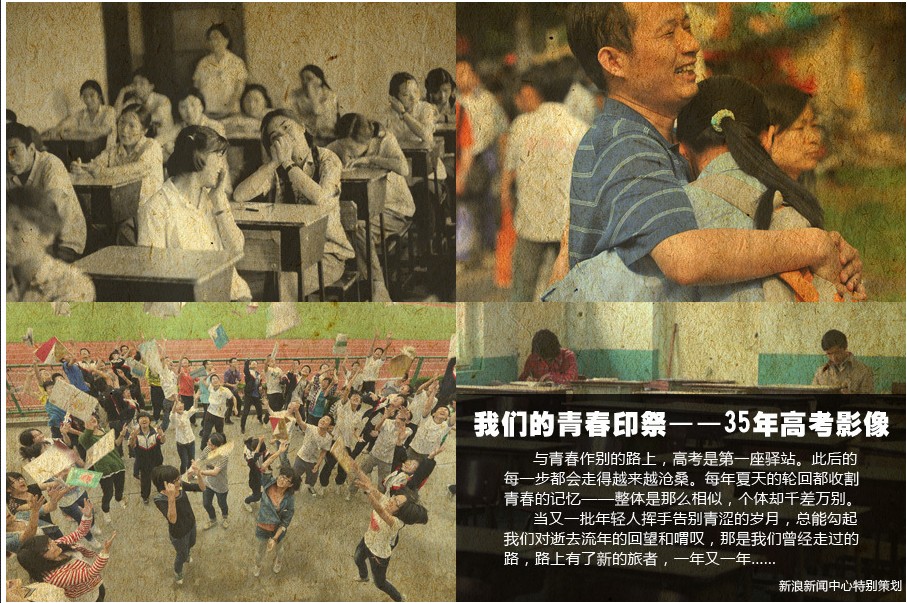

Students flocked to test centers across the country, some traveling by train from their village, clean clothes on their backs and their dreams in tow. The Wall Street Journal posted a photoseries capturing exam-day scenes from across the country, and Sina has published a photoseries stretching across the 35 years since the gaokao resumed after its Cultural Revolution hiatus. Offbeat China reposted the photos with translated captions:

Gaokao is a farewell to youth. After Gaokao, one starts to go through the real ups and downs of life. Summer is the time to harvest memories. Collectively, there seems to be no difference. Yet individually, everyone is so unique. At a time when another generation of youth bid goodbye to their teen years, deep emotions from the old days strike back – it’s a journey we all went through, followed by new comers year after year…

The Globe and Mail’s Mark MacKinnon reports that copies of the test were allegedly available online for up to $1,000 each despite assertions from the Ministry of Education that they were kept under armed guard in secure locations. 73,000 students took the exam in Beijing, according to the China Daily, where eager parents waited and some students planning to sit next year’s gaokao staked out the exam locations to “get a feel” for the experience:

“I have come to the spot since grade one in junior school to feel the tense atmosphere, and thus to make myself better prepared when it is my turn,” said Meng Fanzhao, now in his second year in high school.

“The competition for a prestigious university seemed to start when my son went to school when he was 6 years old. Children compete for higher scores to enter a better middle school, then a better high school. And all this preparation is for today’s fight,” said Zhao Xichen, a father in Shaanxi province, whose child attends gaokao this year.

“I feel my son will be relieved after this final fight, and so will I,” Zhao said.

While the gaokao may still generate fierce competition, its appeal – and the draw of Chinese universities – may be waning. The Global Times’ Gao Lei writes that students still want to go to college, but are increasingly looking elsewhere:

Students don’t believe they can have better prospects if they study in universities in China,” said Xiong Bingqi, an education expert. His concern is emphasized by Long Yongtu, former secretary-general of the Boao Forum for Asia, who remarked in a recent speech that China can only become successful in soft power when it becomes a prime destination for higher education.

Although China made spectacular achievements in building its economy since the reform and opening-up drive, its soft power has continued to lag behind, forcing many promising students to look to other countries for further education. Official data released early this year showed that 70 percent of high school students in Beijing prefer to receive higher education overseas as that would make them more competitive.

Even for those already studying in top Chinese universities like Tsinghua, it is the dream of many to go overseas. It’s no wonder that there is a joke going round that Chinese universities are actually preparatory courses for top US universities.

China’s universities have failed to put up a good fight against competition from the West. While they have been expanding their enrollment quotas to attract more students, the quality of their education has gone in the opposite direction. A lack of innovation and poor management have also obstructed their development.

BBC News spent the past year following students at a high school in Shanghai, one of the first Chinese cities to set limits on homework and mandate minimum exercise requirements for students in an attempt to cultivate a more balanced education based on real learning. Tang Xiangyang, who sat for the exam in 2003, writes for The Economic Observer about the disconnect between some of the questions on today’s exam and the real issues facing modern China:

What should the examiners in Guangdong – the epicenter of China’s transformation – be expecting?

Do young students enjoy living in a world where milk is poisoned, cooking oil is taken from the gutter, pills are made from used shoes and it’s not just the magic mushrooms that are hazardous? If not, what era would they prefer? One from the past, when the air was clean and the water was harmless, or one from the future, which assumes that we can resolve the problems of today?

What about the examiners in Jiangsu?

How will their students resolve the tension between anxiety and patriotism? Perhaps they’ll decide that people can’t simultaneously love their country and worry about their health and safety.

Finally how would the Jiangxi pupils have deciphered their tongue-twisters? They had to balance their pride at China’s economic achievements with their uneasiness at the damaged environment and toxic food.

As hard as the gaokao is, adds Jeremiah Jenne at Jottings from the Granite Studio, “it’s nothing” when stacked up against China’s imperial civil service examination. And despite all the criticism, senior China Daily writer Liu Shinan writes that the gaokao is still the best way forward for Chinese students:

China’s education system may need a fundamental change but we have to admit that the current gaokao system is the only fair way for most children, especially those from unprivileged families, to have a chance of a good future for themselves and their families. This is the reality of this country. With the nation’s economic life dominated by those with vested interests, for those children from ordinary families standing out in the grueling gaokao is the only hope they have for a better future. Telling these children not to work so hard and enjoy a more carefree childhood is telling them to give up their dreams. It sounds humane but is unrealistic.

So do not criticize the gaokao before working out a better way for sustainable economic growth and straightening out other complicated, more influential matters in China’s political and economic lives. Let’s forget about all the good and bad of gaokao and wish the kids success.