This year’s Two Sessions meetings in Beijing have been marked by uncharacteristic outspokenness against official policy, both at the Great Hall of the People and in the media. In particular, Chinese People’s Political Consultative Committee delegate Jiang Hong, a professor at Shanghai University of Finance and Economics, has caused a stir with remarks calling on the government to allow advisors like himself to offer unrestrained suggestions. His remarks were in turn censored from an article in Caixin, which then published another article criticizing the censorship. At this week’s meetings in Beijing, BBC reporter John Sudworth interviewed Jiang before he was hurried away by an official:

“If a society only listens to one voice, then mistakes can be made,” he told us.

“A good way to prevent this from happening is to let everyone speak up, to give us the whole picture.”

“I feel there’s been an increase in things being deleted online – articles and blogs and posts on Wechat,” he continued.

[…] But Mr Jiang’s determined insistence on exercising his right to free speech illustrates how China’s annual parliament is not always quite so rigid and compliant as it first seems.

For the few who choose to use the opportunity, with the media access and at least the pretence of openness, it offers a precious moment in which they can push the boundaries a bit and, in doing so, highlight the debates that are often rumoured to be raging inside the ruling elite.

And Mr Jiang has done exactly that. [Source]

While debates may indeed “rage” inside the closed meetings, most initiatives pass with an overwhelming majority and any dissent is minimized in public reports. Foreign reporters covering the sessions are given little or no information about the discussions that go on during voting, and delegates have been warned against speaking with the press. Didi Kirsten Tatlow reports for the New York Times:

The government says the session this year, and a parallel annual gathering of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, a government advisory body, were the most open ever, with many official interviews arranged for reporters, China Daily reported.

But casual conversation with delegates and their employees on the sidelines of the closing session on Wednesday was difficult.

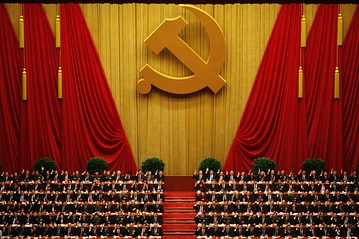

Before the voting, dozens of men in black suits and maroon ties milled inside the Great Hall of the People, their badges identifying them as support staff for the Supreme People’s Court delegates.

One man who was seated, asked whether he was with the court, said, “I’m a working person.” Pressed, he said, “Yes.” Then he stood up and walked away. [Source]

During Premier Li Keqiang’s two-hour press conference—the only time all year reporters are allowed to ask questions of him—all questions are vetted ahead of time. Both foreign and domestic reporters can be reprimanded for making unapproved queries. From Simon Denyer at The Washington Post:

A Chinese reporter from state-run Science and Technology Daily claimed to have been scolded for asking “negative questions” and then threatened by one delegate at the parallel China People’s Political Consultative Conference. “You can’t write whatever you want about companies involved in military industry,” the reporter said he was told. “If you still want this job, you better watch out. I’ve noted down your press number; better watch out or some relevant department might lock you up.”

On Wednesday, Li got 98.4 percent support for his annual economic work report from the National People’s Congress, the largely ceremonial legislature.

As Bloomberg noted, that was actually the highest disapproval rate he has received since taking office in 2013, but it is still a support level a U.S. president could only dream of in Congress. What remains a mystery is who voted against him, and whether they did so voluntarily, or just for show. [Source]

Esther Fung and Rose Yu at The Wall Street Journal noted a change at this year’s press conference, with fewer representatives from ostensibly Western media outlets which actually have ties to the government:

The stage-managing goes into overdrive when it comes to China’s efforts to shed the image that its policymakers can’t handle difficult questions from foreign media. In addition to pre-screening questions, officials have adopted another strategy: Call on foreign-looking journalists who work for foreign-sounding news outlets that actually have links to Chinese state-controlled media.

[…] This year, however, things have been a little different.

Whereas in past years reporters from an Australian radio outfit affiliated with state-run China Radio International have caused a stir, this time around the news outlet, Global CAMG Media Group, seems to have taken a lower profile. China Real Time didn’t find any examples of CAMG journalists asking questions this year in transcripts from the session. A person answering the phone at the company’s Beijing office said he didn’t know whether the firm sent any reporters to cover this year’s meetings.

China Real Time has come across several “foreign media with Chinese characteristics” at the NPC over the past week – but their questions have run the gamut, from softballs on soybean trade to pointed queries on China’s journalism laws. [Source]

But with Jiang Hong’s comments, statements of defiance from property tycoon Ren Zhiqiang and a Xinhua journalist, and an open letter allegedly from “loyal Communist Party members” calling on Xi to resign, resistance to Xi’s brand of media and political control appears to be growing at various levels of society. Andrew Browne at The Wall Street Journal reports on the various way Chinese citizens register their discontent with official censorship:

This is not the Mao era, however much Mr. Xi would like to revive some of the language and political practices of that time, including public confessions and “self-criticism” sessions at party meetings. Today’s population is not so easily cowed—and it has many more ways to register protest.

Some engage in online jousting with censors, using word play to disguise criticisms of government policies and puns to identify top leaders. For instance, Mr. Xi becomes “tricky too-big” or “breathe spirit-bottle”—nonsense terms now banned.

[…] Students are flocking to the West for a liberal college education. Writing in The Australian newspaper last week, Jasmine Yin, who identifies herself as the granddaughter of one of Mao’s favorite generals and who is now studying at New York’s Columbia University, used the Chinese proverb “same bed, different dreams” to describe the gulf that separates young Chinese people from Mr. Xi and his peers in the party. The wish list of her millennial generation: “Less political interference in our lives, more openness to the outside world, dismantling the detested Great Firewall.” [Source]

See also a discussion on ChinaFile on “What’s Driving the Current Storm of Chinese Censorship?” which features CDT’s Anne Henochowicz along with David Schlesinger, Charlie Smith, and Yaqiu Wang.