Sim Chi Yin, China Correspondent reports on The Straits Times (Singapore):

Sim Chi Yin, China Correspondent reports on The Straits Times (Singapore):

The grass mud horse is hardly the first creature or coded term invented by China’s famously vocal netizens but it seems to have caught on in an unprecedented way, said Professor Xiao Qiang of the University of California at Berkeley in the United States, who runs a project monitoring Chinese cyberspace.

Terming it a ‘phenomenon’, he said: ‘It is essentially an online protest and has become a subculture mostly among younger netizens, who are fed up with online censorship and so made up a mascot to express what they really want to say to someone who shuts down their blog.’

This form of political parody is grassroots ‘weapons of the weak’, wrote Tsinghua University sociology professor Guo Yuhua in an online article.

To tackle blogs and sites within the domestic cybersphere, the authorities are also funding a platoon of Web commentators – dubbed by snubbers as the ‘Fifty Cent Party’ – to write postings countering criticism online and to ‘guide’ public opinion.

China’s netizens have fought back in various ways over the years: using proxies to scale the Great Firewall, inventing homonyms like the ‘grass mud horse’ to evade filters, embedding codes or asterisks in words or writing in Chinese characters backwards. A few have tried to sue their service providers for closing down their blogs, with little success.

But despite all the widely reported censorship, room for discussion in Chinese cyberspace has stretched and not shrunk in recent years, noted Prof Xiao.

In all likelihood, they will demand ever greater space, he said.

‘The grass mud horse is a free-speech slogan being collectively shouted by hundreds and thousands of Chinese netizens.

‘That didn’t happen even just five years ago. Instead of submitting to the censors, netizens have become bolder and bolder.’

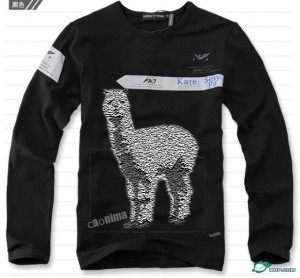

Their latest salvo: a photograph of a young man wearing a T-shirt commemorating the Tiananmen crackdown of June 4, 1989. They have so far evaded the censors’ snip by avoiding the long-banned Chinese characters for ‘liu si’ (6, 4) – using instead Roman numerals for ‘8964’.