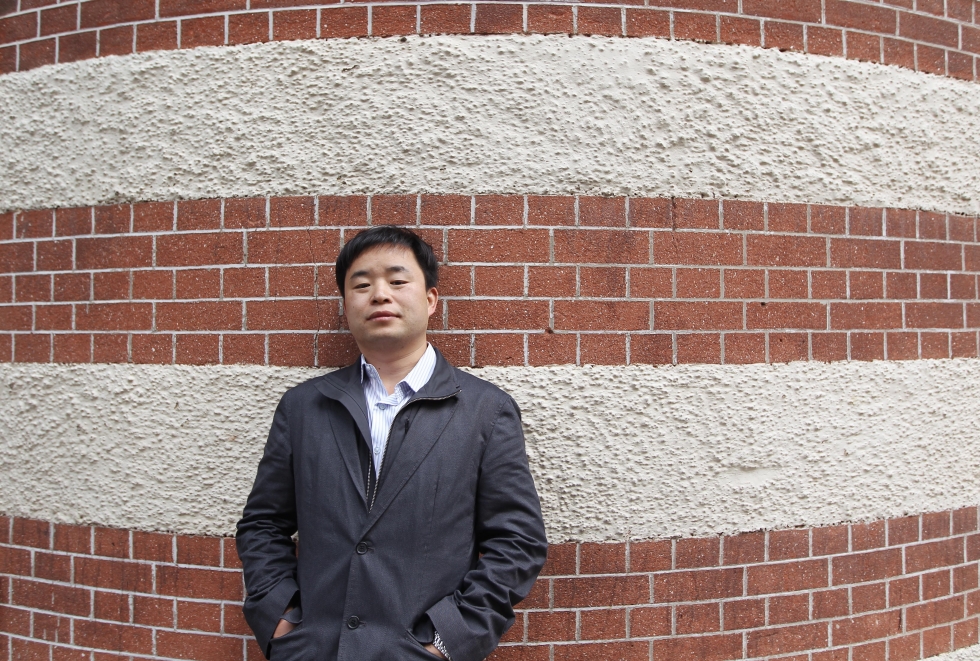

Late last month, writer and free speech activist Murong Xuecun became the target of an online smear campaign consisting of several defamatory articles that were forwarded over 1,000 times on Twitter. In his most recent essay for the New York Times, the author describes the smear campaign, and explains how it can be seen as a government effort to to apply proven methods for influencing online public opinion to the world at large:

[…] The online campaign against Chinese dissidents is not a problem that affects only a small group of individuals. Rather, it is seen as an attempt to manipulate opinion on a global scale.

The Communist Party has come to perceive the freewheeling nature of the Internet a life-and-death issue. While fortifying the Great Firewall to keep undesirable information out of the country, it has also closed a huge number of blogs and increased censorship. In case that wasn’t enough, the government has spent handsomely enlisting a huge number of paid online commentators — professional Internet trolls, numbering possibly in the hundreds of thousands — to create enough noise to interfere with normal online discussion and thereby promote the interests of the Party. They pretend to be independent online but are paid to follow orders.

This huge corps of Internet commentators — popularly called the 50-Cent Party, because they were reportedly paid 50 fen (about 8 U.S. cents) for each post — praises and defends the government, while launching extreme personal attacks on government critics. Until recently, however, the influence of the 50-centers was limited to commenting on China-based websites. Smear campaigns like this have been common on Chinese sites. Only a year ago, it seemed there were just a few isolated trolls on banned, foreign-based sites like Facebook and Twitter. Now the 50-centers are spreading their vitriol beyond China. Fake accounts on Twitter spewing Beijing’s party line have been proliferating. [Source]

Murong Xuecun’s fellow activists Wen Yunchao (aka Bei Fing), Hu Jia, and Wang Dan were also recently subject to a nearly identical online smear campaign. In July, advocacy group Free Tibet identified nearly 100 fake Twitter accounts circulating suspiciously cheerful news about life in Tibetan regions of China.