At The Guardian and on Twitter, Fergus Ryan highlights the likely political sensitivity of Taylor Swift’s new Chinese merchandising venture. Her new line of “merchy” aims to combat widespread counterfeiting and the use of opportunistically registered trademarks in the Chinese market, but may run into other problems.

The singer is launching her own Taylor Swift-branded clothing line next month, on the platforms of local e-commerce giants JD.com and the Alibaba group, with t-shirts, dresses and sweatshirts featuring the politically charged date 1989.

The date – as well as being Swift’s year of birth – refers to her album and live tour of the same name, which she will perform in Shanghai in November.

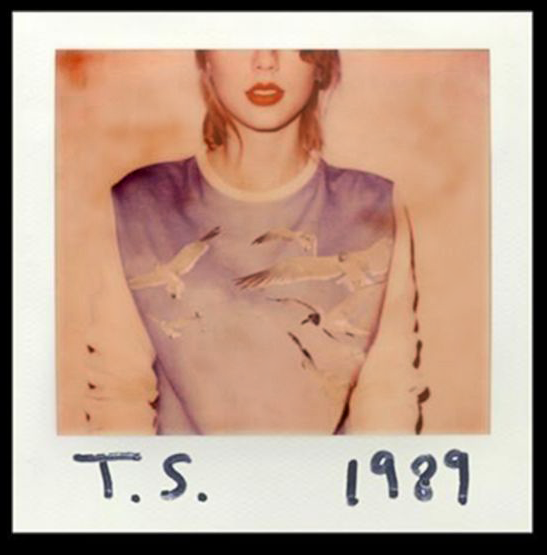

[…] Swift’s US website features bracelets, bags and hairties emblazoned with “T.S. 1989”. For Chinese consumers, the initials could stand for Taylor Swift or Tiananmen Square. It’s not clear whether these items will be made available for Chinese fans. [Source]

.@taylorswift13 is going to sell t-shirts with '1989' on them in China. #awkward #tiananmen pic.twitter.com/QiJJVD08F3

— Fergus Ryan (@fryan) July 22, 2015

T.S. 1989 http://t.co/y5qOa1QY8p pic.twitter.com/C94u7V3q3H

— Fergus Ryan (@fryan) July 22, 2015

If Taylor Swift can't call her new clothing line "1989" in China, she should probably just call it "1984". http://t.co/LDWY2jiaCk

— Kenneth Tan 😷 (@MrKennethTan) July 22, 2015

Online references to the 1989 June Fourth crackdown are heavily censored. Web users have adopted ever more arcane and oblique codes to evade detection, and censors have blacklisted a steadily widening circle of terms in response. On this year’s anniversary, Sina Weibo blocked searches for “64” in Chinese, pinyin, English, and Arabic and Roman numerals, as well as allusive mathematical notations (e.g. “63+1” and ““8的平方” (8 squared)). Chinese homophones such as “柳丝” (willow silk) have also been blocked in the past, along with terms such as “today” or “that day,”

Searches for the year appeared somewhat less thoroughly throttled this year, with “八九” (89), “捌玖” (89 in bankers’ anti-fraud characters), “8jiu” and others blocked but “89” and “1989” not. (Plain usage is more likely to be politically “innocent” than veiled references, though this was not enough to spare the more specific “64” from blocking.) How happily the authorities will tolerate its presence on thousands of teenagers’ clothing, even for “the most powerful person in the music industry,” remains to be seen.

In any case, the sensitive date will have little historical resonance for much of Swift’s Chinese fanbase. Some of Tiananmen’s memory does reach younger Chinese, but the crackdown has generally become shrouded in an enforced “mass amnesia.” Louisa Lim examined this phenomenon in her book “The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited,” and discussed it at The Guardian this week:

When I had first lived in Beijing in 1991, as a student, I’d had urgent, furtive conversations in public parks and deserted streets, where friends confided what they had seen in Tiananmen Square. Over the years these had stopped. Some people who had marched and wept in 1989 now defended the authorities’ actions as necessary. Having witnessed the pain of the post-Tiananmen years, I wanted to discover how memories could be reformatted and how China’s population had become complicit in an act of mass amnesia.

I did a simple experiment to gauge the depth of the forgetting. I took the iconic picture of Tank Man – the young man blocking a column of tanks – to four Beijing campuses. Out of 100 students, only 15 could identify the picture. The others leaned in, eager and wide-eyed, asking: “Is it from South Korea?” and “Is it in Kosovo?” One young woman asked what I was writing about. I answered directly: “About liu si [June fourth].” She looked blank. “What is that?” she asked. “I don’t know what that means.” [Source]

See more on Tiananmen-related censorship and other issues via CDT.

Updated at 20:27 PDT on Jul 23, 2015:

@cctvnews posted about @taylorswift13 's clothing line on FB yesterday. What's missing? http://t.co/28kOKOxUJ1 pic.twitter.com/15i5lFWjvX

— Shanghaiist (@shanghaiist) July 24, 2015

(“1989” is blacked out in the image, though the Facebook post does name the album and tour in its main text.)