The following censorship instructions, issued to the media by government authorities, have been leaked and distributed online. The name of the issuing body has been omitted to protect the source.

All websites, including departments involved in coordinating interactive sections, prominently repost the article "A Police Officer Involved in the RYB Investigation Speaks From the Heart." You may use a different title. (November 30, 2017) [Chinese]

On Monday, the Chaoyang Public Security Bureau issued a statement on its investigation into claims of abuse at the RYB New World Kindergarten, which had stoked public outrage already inflamed by another scandal centered on a Shanghai daycare center. A previously published directive on the RYB case sought to contain related coverage and commentary in order to dampen the uproar. The police notice, posted on Weibo, said that most of the accusations of abuse had been made up, and that although a hard drive containing potential video evidence had been damaged by being improperly shut down, some footage had been recovered and showed no sign of mistreatment. A subsequent directive ordered websites to "resolutely prevent malicious hyping" of the notice, but it has nevertheless been the target of considerable skepticism and mockery, which the article promoted by the above directive seeks to confront.

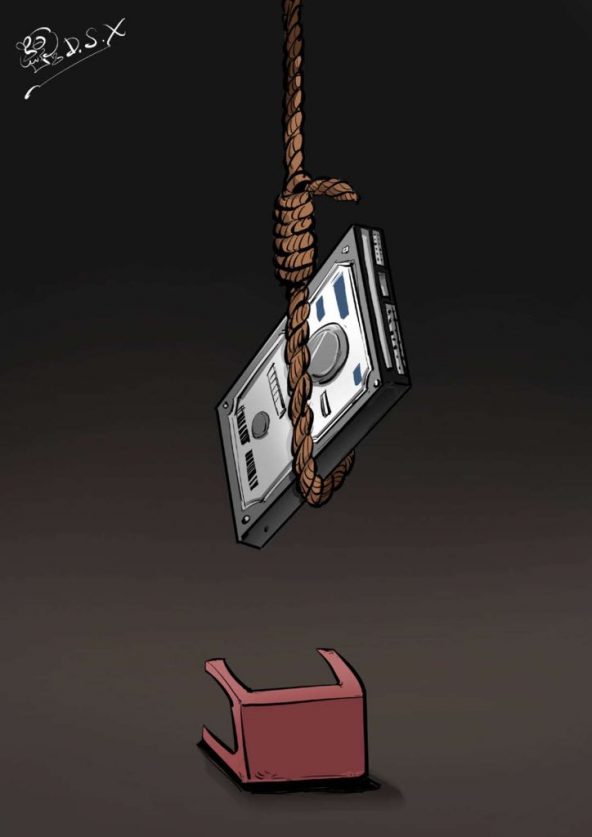

The hard drive failure, for example, seemed improbably politically convenient to some. A now-deleted WeChat post by Jason Ng, translated at CDT, lists several similarly opportune malfunctions in cases from recent years. The new Magpie Digest newsletter noted that "the incident has also led the public to loudly question: who is the surveillance for, and how can it hold institutions accountable, if the authorities are the only ones who can access the footage?" Such sentiments have spawned the phrase "the hard drive is surnamed ‘Party,’" after Xi Jinping’s 2016 call for loyalty from the media. Cartoonist Dashixiong depicted the drive’s supposed sacrifice:

The article promoted by this latest directive is a response to such suspicions purportedly written by an officer involved in the case, and presented by blogger "Shuimu zhentan she." The blogger, who published a number of pro-police articles during the similarly controversial Lei Yang police brutality case, says that the main text was written by one of his social media followers. The officer begins by lamenting that he and his colleagues have worked tirelessly for the past week; that he has slept only an hour or two a night, barely going home or seeing his young daughter, only to be confronted by online invective against the police. He remonstrates with groups he sees as responsible: parents or others whose public statements ignited or fueled the controversy, media workers and social media users who added oil, and the manufacturer of the surveillance system whose product failed and who left it to the police to explain that to the public. He maintains, though, that the footage recovered, covering nearly three weeks, is enough to support the conclusion that no mistreatment took place. Those who remain doubtful or suspicious of the police notice’s account, he says, should provide contrary evidence, and not "mislead others with theories, guesses, and deductions."

As Jeremiah Jenne wrote at Radii China this week, however, "when the official response is obfuscation and censorship, it makes it harder to believe the outcomes of investigations, especially when those outcomes would seem to benefit the side of social order. […] Official action to better supervise these institutions is a good start, but there also needs to be greater transparency — and less of a stranglehold on independent reporting — when scandals do occur." Heightened supervision is already on the way, with prospective measures including legislation, new staff checks, surprise inspections, and more thorough camera coverage—potentially boosted, in future, by real-time AI analysis. But prospects for the greater transparency and independent media scrutiny Jenne called for appear much dimmer.

Magpie Digest reported this week that many on Chinese social media are also concerned by the lack of aggressive investigatory reporting, blaming not only official censorship but commercial pressures that incentivize speed and sensationalism over depth and accuracy. It concluded its overview of reactions to the case by noting a range of tone "from defeated frustration to simmering anger, threaded through with an utter lack of surprise at the outcome." This WeChat post was offered as a sample:

"The way this has developed, it is like we are all just playing a game of Werewolf. Nobody knows anything for sure. People are picking sides at random. The government has got a history of lying, and their statement is so terrible no one believes them. The only Werewolf hunter who can prove their own identity (the surveillance records) has a malfunctioning gun. Some people think the parents’ story was too outrageous, but I cannot help but ask: what do they stand to gain? But. The very fact that a matter of public concern has turned into a game of Werewolf, whose fault is that? Night has fallen, please close your eyes." [Source]

Meanwhile, RYB announced on Wednesday that "there have been additional parent complaints regarding other RYB-branded kindergartens" in China.