A stream of recent analysis and news coverage has continued to examine the development of advanced surveillance and security technologies alongside mass detention camps in Xinjiang, their proliferation elsewhere in China and beyond, and the various investments and research partnerships through which Western firms and institutions are involved. At The New York Times on Sunday, for example, Paul Mozur described the spread of facial recognition systems designed to automatically identify members of Xinjiang’s Uyghur ethnic minority to other parts of China including Wenzhou and Hangzhou. Mozur included details of several companies behind these systems, as well as their current or former investors, and their evident awareness of the business’s political sensitivity.

The Chinese A.I. companies behind the software include Yitu, Megvii, SenseTime, and CloudWalk, which are each valued at more than $1 billion. Another company, Hikvision, that sells cameras and software to process the images, offered a minority recognition function, but began phasing it out in 2018, according to one of the people.

[…] In a statement, a SenseTime spokeswoman said she checked with “relevant teams,” who were not aware its technology was being used to profile. Megvii said in a statement it was focused on “commercial not political solutions,” adding, “we are concerned about the well-being and safety of individual citizens, not about monitoring groups.” CloudWalk and Yitu did not respond to requests for comment.

[…] The A.I. companies have taken money from major investors. Fidelity International and Qualcomm Ventures were a part of a consortium that invested $620 million in SenseTime. Sequoia invested in Yitu. Megvii is backed by Sinovation Ventures, the fund of the well-known Chinese tech investor Kai-Fu Lee.

A Sinovation spokeswoman said the fund had recently sold a part of its stake in Megvii and relinquished its seat on the board. Fidelity declined to comment. Sequoia and Qualcomm did not respond to emailed requests for comment.

[…] Ethnic profiling within China’s tech industry isn’t a secret, the people said. It has become so common that one of the people likened it to the short-range wireless technology Bluetooth. Employees at Megvii were warned about the sensitivity of discussing ethnic targeting publicly, another person said. [Source]

Here’s a translation of an ad from Chinese startup CloudWalk that describes a dark use case. Basically if a Uighur has a barbecue or family visit, police are called. pic.twitter.com/IrbGqfMZTn

— Paul Mozur (@paulmozur) April 14, 2019

In another bit of not-so subtle advertising, CloudWalk lists key control points for such tech, and shows photos of four mosques. It includes the Id Kah mosque in Kashgar, where there are more than 100 high-powered cameras and a propaganda shot of Xi Jinping sits over the Mihrab. pic.twitter.com/Y914px8CxJ

— Paul Mozur (@paulmozur) April 14, 2019

(The Xinjiang government’s information office recently told The Wall Street Journal that such cameras are for worshippers’ safety, saying that “the recent mass shooting in New Zealand that harmed so many innocent lives is a strong warning. The goal of improving security at mosques is to protect the ability of the Muslim community to hold normal, orderly religious activities.”)

The same softwares are being used to track other vulnerable groups, albeit in a more targeted way.

— Paul Mozur (@paulmozur) April 14, 2019

Many cities have lists of the following:

Long-term residents (w/hukou)

Temporary residents (in hotels)

Those with driver’s licenses

Those with a history of drug use

Criminals at large

People w/ criminal record

People w/ a record of drug use

The mentally ill

Petitioners— Paul Mozur (@paulmozur) April 14, 2019

Last September, CDT translated a list of more than 200 such categories that had been posted online by an anonymous user claiming to be a disgruntled public security employee.

There is also a national list of Uighurs who are traveling outside Xinjiang. Which would help the systems not just determine whether someone belongs to the ethnic minority, but who they are. There are also some places with databases of foreigners.

— Paul Mozur (@paulmozur) April 14, 2019

There’s a fair bit of advertising for the next gen Chinese startups providing these services. Many have scrubbed more cavalier ads showing racial identification capabilities. I’m partial to this one from Megvii (since taken down): pic.twitter.com/mBl8DWezhB

— Paul Mozur (@paulmozur) April 14, 2019

No, sourcing said they scrubbed about 1.5 years ago. Megvii employees were also explicitly warned not to talk about this type of racial targeting work for Chinese police.

— Paul Mozur (@paulmozur) April 14, 2019

For a long time democracies had a monopoly on cutting edge tech. China’s changing that. New tech is being built to authoritarian needs, often targeting vulnerable groups. It’s time for many in the U.S. to think about what constitutes unacceptable involvement in such practices.

— Paul Mozur (@paulmozur) April 14, 2019

Mozur, together with the Times’ Chris Buckley and Austin Ramzy, recently produced an account of the tight security controls in and around Kashgar. In a follow-up this week, he described the obstruction they encountered during their reporting from Xinjiang.

The Center for a New American Security’s Elsa B. Kania also commented on Mozur’s article on Twitter, focusing on the corporate players and their overseas expansion and other ties, and noting SenseTime’s recent exit from a partnership in Xinjiang. From her thread:

Among the most striking aspects of this troubling reporting is the involvement, unsurprisingly, of some of China's most prominent artificial intelligence companies, which have often been celebrated as successful 'unicorns.' https://t.co/PoGSL2ydUb pic.twitter.com/lgrsAB4gMH

— Elsa B. Kania (@EBKania) April 15, 2019

I'd argue that these valuations have been questionable and problematic from the start, including because of the extent to which their 'value' as companies has been inflated by Party-state demands for surveillance technologies, which have been practically astronomical.

— Elsa B. Kania (@EBKania) April 15, 2019

In this regard, I don't think the number of "AI unicorns" in China is a good metric for it's emergence ass a leading player in AI, and this is a good and troubling example of how the intersection of ideology and state intervention can distort markets.

— Elsa B. Kania (@EBKania) April 15, 2019

Moreover, it's worth noting that many of the companies that are deeply complicit in these activities have been quite actively expanding globally, including pursuing partnerships with Western companies and universities in the process.

— Elsa B. Kania (@EBKania) April 15, 2019

Beyond the national security concerns raised by such collaborations, there are also concerns of ethics and human rights in play, including the partnership between MIT and Sensetime, which has been quite active, apparently. https://t.co/Y4GHvKK1MR

— Elsa B. Kania (@EBKania) April 15, 2019

It's noteworthy SenseTime has just sold out of a joint venture in Xinjiang, but this seems to be only symbolic, since its research will continue to be used in Xinjiang, and clearly this targeting is not limited to Xinjiang but extends throughout China. https://t.co/tAFu1wsXwd

— Elsa B. Kania (@EBKania) April 15, 2019

The Financial Times’ Christian Shepherd reported SenseTime’s exit from its XInjiang joint venture on Sunday:

It has now sold its 51 per cent stake in the joint venture, Tangli Technology, to Leon [its former partner], which said Tangli would continue with its strategy and that its research team had mastered key technologies.

[…] SenseTime’s international backers include Fidelity International and Qualcomm, and analysts said it may have been wary of putting off foreign investors as it plans for an IPO. The company announced a partnership with Massachusetts Institute of Technology last year.

[…] A spokeswoman for SenseTime, which has its headquarters in Hong Kong, said the move was part of a strategy review and that the company “no longer works with Leon and barely has any business in Xinjiang”. [Source]

Pete Sweeney at Reuters’ BreakingViews described SenseTime’s departure as "a fig leaf":

[…] The deal may ease some PR risk before a mooted offshore flotation, but the $6 billion startup still sells facial recognition software to security forces. Monday’s move provides foreign backers like Fidelity International with only thin reputational cover.

Along with helping municipalities manage traffic and prevent crime through technology, Beijing’s spending on internal security in the People’s Republic has become a business opportunity. The video surveillance market alone is tipped to be a $20 billion industry in China by 2022, according to Bernstein research, up from $8 billion in 2017. That helped companies like Shenzhen-listed security camera maker Hangzhou Hikvision briefly become foreign investor darlings. But offshore enthusiasm for the sector has visibly waned.

[…] By selling its stake in Tangli, SenseTime avoids the necessity of explaining one of its most obviously problematic businesses in IPO documents, especially if it plans a New York listing. Since American politicians are already talking about sanctioning individuals and companies supporting the crackdown in Xinjiang, the move also attenuates political risk. But SenseTime and its peers still sell tools that enable the some of the worst tendencies of Chinese officialdom. They will almost certainly export to questionable regimes abroad too. SenseTime’s investors get to wash Xinjiang off their hands, but there is sure to be plenty of dirt left over. [Source]

In July last year, SenseTime also shed its 49% stake in SenseNets, a facial recognition firm it had helped found in 2015. Earlier this year, SenseNets was accused of failing to safeguard enormous amounts of data collected through its systems, highlighting the risk of unauthorized abuse of surveillance data beyond the dangers posed by its intended use. South China Morning Post’s Li Tao described the incident in a recent profile of the company:

Victor Gevers, co-founder of non-profit organisation GDI.Foundation, tweeted in February that an online database belonging to SenseNets containing names, ID card numbers, birth dates and location data was left unprotected for months. The exposed data also showed about 6.7 million location points linked to people, tagged with descriptions such as “mosque”, “hotel”, “internet cafe” and other places where surveillance cameras were likely to be found.

Instead of going on the offensive over the Gevers tweet, SenseNets has adopted a different approach and remained silent. A call to the company’s general phone number listed on its website was answered by a female representative who said the company does not have anyone in charge of media relations and there was no need for an interview.

[…] SenseNets specialises in three areas: facial recognition, crowd analysis and human verification. Facial recognition allows the company to capture, compare, identify and monitor targeted personnel which plays a positive role in social security management, criminal investigation analysis, and anti-terrorism activity, while crowd analysis can improve the statistical accuracy of analysing big groups of people leading to quicker decision-making, according to the company’s website.

Meanwhile, human verification technology allows comparisons between facial pictures and the images stored on Chinese official ID cards, allowing real-time identification of people. The company’s products have been used by a variety of industries such as security, financial and medical services, and within smart retail, but the company is mostly known for its work with police forces in China. [Source]

On Sunday, an anonymous researcher on Twitter posted apparent details of a similarly unsecured database fed by internet-accessible cameras, themselves protected only by easily guessable default login credentials. This data, too, suggests a heavy focus on automated identification of Uyghurs.

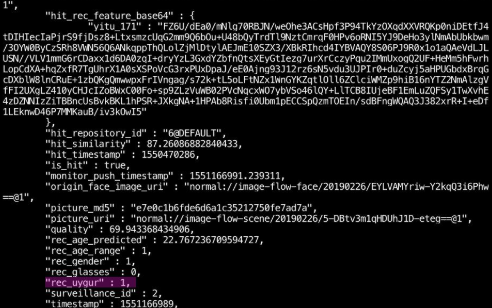

The company @YITUTech which is China's leading AI company and is a NIST/IARPA winner has developed Facial Recognition Technology which has an ethnically profiling function targeting parameter for Uygurs. [1/4] pic.twitter.com/X46AStITz4

— @Night_Wing_Ding (@Night_Wing_Ding) April 14, 2019

Multiple surveillance systems using @YITUTech Facial Recognition Technology which were accessible to the internet without any form of authentication full with millions of recorded faces stored in MongoDB databases and indexed by Shodan. [2/4] pic.twitter.com/kNJ1NhUfTI

— @Night_Wing_Ding (@Night_Wing_Ding) April 14, 2019

The @YITUTech mass surveillance systems are using Tiandy network cameras for their live-feed. These camera systems still use default credentials like admin/admin and were also accessible via the internet [3/4] pic.twitter.com/2J1p0cQhec

— @Night_Wing_Ding (@Night_Wing_Ding) April 14, 2019

The @YITUTech database contained 14.1 million mugshots of Chinese people of which 378,740 were recognized as Uygur as a training data because from a real data source from police stations to identify Uygurs more efficiently and a higher hit rate. [4/4] pic.twitter.com/vAQGAEjQPI

— @Night_Wing_Ding (@Night_Wing_Ding) April 14, 2019

While Paul Mozur’s report at the NYT documents the spread of surveillance technologies from Xinjiang across China, a new report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute shows their proliferation around the globe. The ASPI report maps the growing international footprint of China’s tech companies, including 404 research partnerships, 75 "Smart City" or public security projects, 52 5G initiatives, 119 R&D centers, and 56 undersea cables. One section focuses on the companies active in XInjiang:

The complicity of China’s tech giants in perpetrating or enabling human rights abuses—including the detention of an estimated 1.5 million Chinese citizens and foreign citizens—foreshadows the values, expertise and capabilities that these companies are taking with them out into global markets.

[…] Many of the companies covered in this report collaborate with foreign universities on the same kinds of technologies they’re using to support surveillance and human rights abuses in China. For example, CETC—which has a research partnership with the University of Technology Sydney, the University of Manchester and the Graz Technical University in Austria—and its subsidiary Hikvision are deeply implicated in the crackdown on Uyghurs in Xinjiang. CETC has been providing police in Xinjiang with a centralised policing system that draws in data from a vast array of sources, such as facial recognition cameras and databases of personal information. The data is used to support a ‘predictive policing’ program, which according to Human Rights Watch is being used as a pretext to arbitrarily detain innocent people. CETC has also reportedly implemented a facial recognition project that alerts authorities when villagers from Muslim-dominated regions move outside of proscribed areas, effectively confining them to their homes and workplaces.

[…] According to reporting, Huawei is providing Xinjiang’s police with technical expertise, support and digital services to ensure ‘Xinjiang’s social stability and long-term security’.

Hikvision took on hundreds of millions of dollars worth of security-related contracts in Xinjiang in 2017 alone, including a ‘social prevention and control system’ and a program implementing facial-recognition surveillance on mosques. Under the contract, the company is providing 35,000 cameras to monitor streets, schools and 967 mosques, including video conferencing systems that are being used to ‘ensure that imams stick to a “unified” government script’.

Most concerningly of all, Hikvision is also providing equipment and services directly to re-education camps. It has won contracts with at least two counties (Moyu and Pishan) to provide panoramic cameras and surveillance systems within camps. [Source]

Research partnerships like those highlighted by ASPI have been attracting increased attention, especially that of first Google and more recently Microsoft. Highlighting the cross-border nature of AI development as one of five key points gleaned during the first year of his ChinAI email newsletter, Oxford University’s Jeffrey Ding recently emphasized Microsoft’s role. "The seeds of China’s AI development are rooted in Microsoft Research Asia (MSRA) in Beijing," he wrote, while "at the same time, MSRA has been essential for Microsoft." Last week, The Financial Times’ Madhumita Murgia and Yuan Yang reported on some of the more sensitive fruits of this collaboration in the form of research into image and text analysis that could be used for surveillance and censorship, respectively.

Three papers, published between March and November last year, were co-written by academics at Microsoft Research Asia in Beijing and researchers with affiliations to China’s National University of Defense Technology, which is controlled by China’s top military body, the Central Military Commission.

[…] Samm Sacks, a senior fellow at the think-tank New America and a China tech policy expert, said the papers raised “red flags because of the nature of the technology, the author affiliations, combined with what we know about how this technology is being deployed in China right now”.

[…] Adam Segal, director of cyber space policy at the Council on Foreign Relations think-tank, noted the revelation comes at a time US authorities, including the FBI, have put academic partnerships with Beijing “under the microscope” because of fears Chinese students and scientists working on “frontier technologies” may end up assisting China’s People’s Liberation Army. [Source]

The New York Times’ Jane Perlez reported on Sunday on a round of U.S. visa cancelations and reviews of Chinese academics with suspected ties to intelligence agencies.

The Register’s Katyanna Quatch reported this week that a National University of Defense Technology researcher was also among the recipients of facial recognition data shared by IBM:

IBM shared its controversial Diversity in Faces dataset, used to train facial recognition systems, with companies and universities directly linked to militaries and law enforcement across the world.

The dataset contains information scraped from a million images posted on Flickr, a popular image sharing website, under the Creative Commons license. It was released by IBM in the hopes that it could help make facial recognition systems less biased.

[…] “Given how the Chinese government has been using AI facial recognition systems in Xinjiang, in the perpetration of large-scale human rights abuses against Uighur Muslims, it’s definitely possible that the training data released by IBM could be used for insidious AI applications,” Justin Sherman, a cybersecurity policy fellow at New America, a Washington, DC-based think tank, told The Register.

“But that doesn’t necessarily mean IBM shouldn’t release this kind of data, or that other companies or groups should put a stop to the open nature of AI research. Most AI applications are dual-use—they have both civilian and military applications—and so it may be impossible to distinguish between what is and is not a ‘dangerous’ AI application or component.” [Source]

Alex Joske, one of the authors of the report cited above, discussed this kind of engagement at ASPI’s The Strategist blog last week:

Collaboration with the PLA often crosses a red line, but activities that indirectly benefit the Chinese military pose a tough challenge. Military–civil fusion, the Chinese government policy that’s pushing the PLA to cultivate international research ties, is also building greater integration between Chinese civilian universities and the military. As ASPI non-resident fellow Elsa Kania has pointed out, Google’s work with Tsinghua University is worrying because of the university’s growing integration with the PLA.

This raises a troubling question: if a company, government or university is unable to control collaboration with overt Chinese military entities, how can it effectively manage more difficult areas, like collaboration with military-linked entities?

Without clear policies and internal oversight, Western tech firms that don’t intend to work with the PLA may have employees who are doing so. Greater debate and robust policies are needed to ensure that universities and companies avoid contributing to the Chinese military and technology-enabled authoritarianism, and don’t inadvertently give fuel to those wanting an end to all collaboration.

A starting point here is for governments to begin setting out clear policy guidance and improving export controls to target entities that universities and companies should not be collaborating with. In the meantime, self-regulation and internal oversight by these companies will help address government concerns—and help inform future regulation. Civil society—NGOs and media—can also develop resources to help universities improve their engagement with China. ASPI’s International Cyber Policy Centre is currently developing a database of Chinese military and military-linked institutions for this purpose. [Source]

Beyond the tech sector, the BBC’s Robin Brant confronted Volkswagen CEO Herbert Diess on Tuesday about his company’s factory in Urumqi, a joint venture with state-owned automaker SAIC, asking if he was "proud to be associated" with China’s actions in the region. Diess responded that he "was not aware of that."

Particularly frustrating because the evidence base is so rich: Chinese gov ads for camp construction contracts, satellite images, Chinese police statements on numbers interned, earlier propaganda showing prison-like conditions, testimony of former employees and victims… https://t.co/w7ZpIGuEFP

— Rian Thum (@RianThum) April 16, 2019

The @UyghurCongress sent letters to @VWGroup Chief Executive Herbert Diess in response to recent comments on the situation in the Uyghur region of China.@BBCNews' @RobindBrant asked if he knew about the detention of over one million. Diess said:

"I'm not aware of that, no." pic.twitter.com/1nGmfV23VZ

— WorldUyghurCongress (@UyghurCongress) April 17, 2019

Spokesperson tried to backtrack saying VW “aware” of treatment of Uighurs in Xinjiang & has taken active steps to address situation. Have Uighurs & German politicians really applauded VW as company claims? Why did VW build plant there in first place?https://t.co/42BfE5YfIJ

— Thorsten Benner (@thorstenbenner) April 18, 2019