On Thursday, the Beijing offices of Yirenping, a public health and social justice NGO, were raided by police, who took computers and other materials and locked employees out of the building. As Yirenping co-founder Lu Jun told the Washington Post in an article last week, Yirenping has felt increasing pressure as Xi Jinping’s administration has tightened the reins on civil society groups in the country. But the recent raid also appears to be tied to detention of five feminist activists—Wu Rongrong, Li Tingting (aka Li Maizi), Zheng Churan (aka Da Tu), Wei Tingting, and Wang Man—all of whom had ties to the organization. Yirenping has actively advocated for their release since they were detained on the eve of International Women’s Day on March 8. Lu Jun, who is currently in the U.S., announced the raid in an email to friends and supporters. Sui-Lee Wee reports for Reuters:

Lu Jun, co-founder of Yirenping, an anti-discrimination NGO, said about 20 police officers broke into its offices in the early hours of Tuesday, taking away financial receipts, project contacts and several computers and laptops.

[…] Lu said before the search, police had taken his colleague, a man surnamed Cao, into custody for several hours and entered the office with Cao. Cao had been involved in a project on public interest law and has since fled Beijing, according to Lu.

Lu said he believed the raid was linked to his calls for the release of five women activists, who were detained just over two weeks ago, apparently for planning to demonstrate against sexual harassment on public transport.

“I feel the message is that the police want to suppress my calls for solidarity with these women rights activists,” Lu said in a telephone interview from New York, where he is a visiting scholar. “The second signal is that striking down NGOs is a priority.” [Source]

Andrew Jacobs of the New York Times has more on the raid:

Mr. Lu said the authorities carted away files, computers and laptops, and briefly detained one of the center’s employees before changing the locks on the doors.

“We can’t even get into the offices, and the police won’t give us any information,” said Mr. Lu, speaking from New York, where he is a visiting scholar at the U.S.-Asia Law Institute at New York University. He said the center’s five employees, fearing for their safety, had left the Chinese capital.

It was unclear if the authorities intended to close the offices for good. [Source]

At the Washington Post, William Wan puts the raid in the context of China’s bid for the 2022 Winter Olympics:

The raid happened on the same day the International Olympic Committee arrived in Beijing to begin a four-day inspection to determine whether Beijing should host the 2022 Winter Olympics. The convergence was noted by human rights groups as the latest sign the Chinese government intends to ignore international concerns and specific stipulations laid out by Olympic organizers.

When Beijing was chosen to host the 2008 Olympics, many had hoped that it would help improve the government’s human rights records. But oppression of activists and harassment of NGOs has only worsened, rights groups say.

Calling the Olympic inspection and Yirenping raid “deeply ironic,” Maya Wang, a Human Rights Watch expert, noted that the Olympic Committee’s recently revised strategy document, called Olympic Agenda 2020, “obliges host governments to sign a contract with an explicit anti-discrimination clause.” [Source]

Some observers have said they believe the detention of these prominent activists will lead to a “feminist awakening” in China—and indeed, supporters from a broad swath of Chinese society have spoken out against their detention. Several supporters have subsequently faced repercussions from authorities. Sixteen activists who went to the detention center to demand medical care for Wu Rongrong, who suffers from Hepatitis B, were briefly detained over the weekend. University students have been warned against pledging support for the five in a series of petitions that have been distributed online. For the New York Times, Didi Kirsten Tatlow reports:

A notice from the Student Affairs Office of a university in Guangzhou, posted on social media, read: ‘‘There are reports that students at 10 universities have signed a petition. Please ensure all institutes quickly hold activities to deeply penetrate student and classroom circles, investigate, and do educational and dissuasive work.’’

The pushback had the effect of publicizing the petition. ‘‘If they hadn’t issued the notice, not that many people would have known about this,’’ wrote a student who posted it, who other feminists said was at the South China University of Technology. ‘‘Now the whole university knows.’’

Students were called in for ‘‘guidance’’ meetings with university officials or teachers, a student at another university wrote in a social media message.

‘‘Initially I didn’t think too much of it,’’ she wrote. Her philosophy professor supported the feminists, so didn’t go too hard on her.

‘‘But others have had a different experience,’’ she wrote. ‘‘Students who were out of town were called back. I heard some were warned so severely they were frightened and in tears.’’ [Source]

A petition distributed at Sun-Yat Sen University in Guangzhou, the alma mater of Zheng Churan (aka Da Tu), has been translated by Libcom.org. The same post features an essay by Li Weizhi, the partner of Zheng Churan, about the mutual solidarity between China’s feminist activists and labor activists. Li writes:

During the sanitation workers’ strike in Guangzhou University Town in 2014, Da Tu was on the spot and later wrote, from a gender perspective, a news report “Look! Women are Fighting!” It reflected the subjectivity of female workers in this strike, inspiring and encouraging all workers, and smashed the stereotype of always men-dominated strikes in the minds of outsiders.

Women’s rights activists like Da Tu have always paid close attention to workers’ rights and interests. Therefore, it is not surprising that when they are kept in detention, workers come with their support and solidarity.

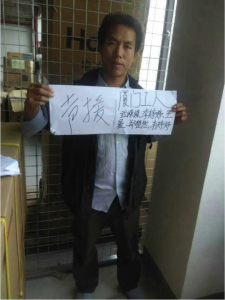

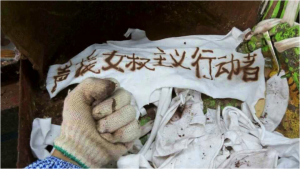

Many warmhearted workers from Xiamen expressed their support for these five detained activists with photos.

“Support Women’s Rights Activists!” Was this slogan written by a fellow worker with rust or motor oil? Seeing her worn-out glove, I felt sad but also deeply grateful.

One female worker holding the poster “We Can Fight Against Sexual Harassment! You Should NOT Disturb!” Some friends have commented, “I have never been so awakened!”

[Source]

Other activists who are associated with the detained five have gone into hiding out of fear of being detained themselves. The Chuan blog interviewed one, who spoke anonymously, about the possible reasons authorities targeted these five activists at this moment:

Chuan: One analysis is that this is related to the feminist petition to cancel CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala.5 What do you think?

Anonymous: There’s definitely some relation, but I don’t think it’s as big as [some] imagine. It’s occurred to me before that some gender equality people would get arrested during Xi’s Jinping’s administration. Because in 2013, when Xi had just assumed office, at that time I was in Guangzhou with [some of the people now being detained] organizing a training workshop for college students, also related to gender equality. That was the most difficult [狼狈] workshop I’ve ever done. We had arranged to do it in a hotel. We had 30-some people, and as soon as we tried to enter, we were kicked out. So we tried three other hotels. None were willing to let us in… And this was very similar to the present situation: all the students from Guangdong were phoned by their fudaoyuan [political counselors]6, who told them [not to participate], and five or six actually [decided not to participate], and afterwards the school kept [harassing] them. And at the time the Guobao [secret police]7 followed us around all day… So already at that time it occurred to us that Xi’s assumption of office might be a disaster for gender equality.

C: At the time I asked someone about this, and she thought it wasn’t that the authorities were specifically targeting the topic of gender equality, so much as it was part of a general crackdown on civil society. You disagree?

A: For [several] years now [the NGO that organized that workshop] has organized at least ten workshops every year, most unrelated to gender, and that was the one they chose to suppress… LGBT-related activities have also been targeted, especially in Beijing. Last year around June 48, at least twenty LGBT-related events were forced to be canceled…. Even watching films together wasn’t allowed. [Source]

The five activists have been criminally detained on suspicion of “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” but have not yet been charged. Li Tingting’s lawyer, Yan Wenxin, provided an account of his meeting with her, which has been translated by China Change. Legal scholar Jerome Cohen writes in the South China Morning Post that the women’s detention and potential prosecution “make a mockery” of Xi Jinping’s proclaimed commitment to “rule of law.” The women were detained before enacting a campaign to raise awareness of sexual harassment on public transportation, despite the fact that sexual harassment is illegal under Chinese law:

These events are especially puzzling because the fourth plenum of the 18th party congress last autumn trumpeted a new party commitment to the “rule of law”.

Although ambiguous, “rule of law” at a minimum suggests that the government should not persecute those who seek to reasonably support its laws and policies.

Of course, every country’s legal system needs to be rooted in local conditions. “Rule of law” in China need not mean precisely what it means in the United States or elsewhere: part of what it means to be a sovereign nation is for that nation to define its own laws, guided by its own values. Inevitably, “rule of law” in China is currently guided by the pre-eminent importance of ensuring stability and private compliance with public rules.

Yet the Chinese government would be dropping a stone on its own foot by prosecuting Wu, Wang and their fellow detainees. The government, after all, has publicly acknowledged that it needs private assistance to stop official lawlessness. [Source]

So far, the Chinese government has responded to statements of concern about the detentions of the five activists from foreign governments by declaring that, “No one has the right to ask China to release relevant persons.”

Human Rights in China has compiled a timeline of the case of the five detained activists together with other resources and international calls for action.