The following censorship instructions, issued to the media by government authorities, have been leaked and distributed online.

From the Beijing Cyberspace Administration Oversight Center: Find and delete all introductions, online encyclopedia entries, film reviews, recommendations, and other articles related to the August 2017 South Korean film “A Taxi Driver.” (October 4, 2017) [Chinese]

South Korean historical drama “A Taxi Driver” (택시운전사), which debuted on August 2, is inspired by the story of an unidentified Seoul cabbie who in desperate need of a fare takes a German journalist on the long ride into Gwanju, where the two navigate the violent military crackdown on the May 18, 1980 Gwanju Uprising. The film has been selected as South Korea’s entry for Best Foreign Language Film at the 90th Academy Awards, and initially attracted much interest in China and a 9+ score on Chinese entertainment rating platform Douban before the listing was harmonized. (Elsewhere, the film is currently enjoying a “94% fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes.)

The notable parallels between the June 4th, 1989 crackdown in Beijing—an event whose memory Chinese authorities have worked hard to conceal—and the similarly student-led movement in South Korea made the popular South Korean film an easy candidate for censorship in China.

Just watched this movie tonight. It's a must-see, I'll be surprised if it shows in China. https://t.co/7R82yncKK4

— Joanna Chiu (@joannachiu) October 3, 2017

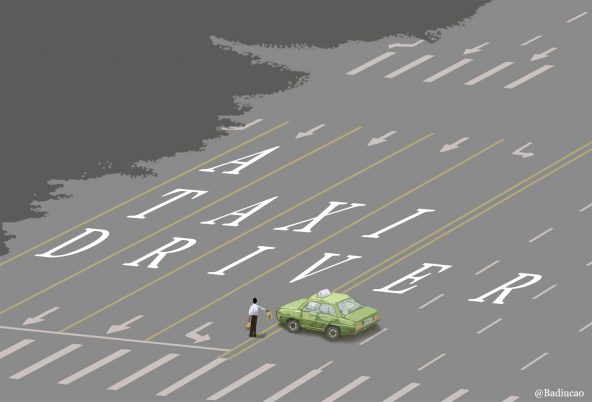

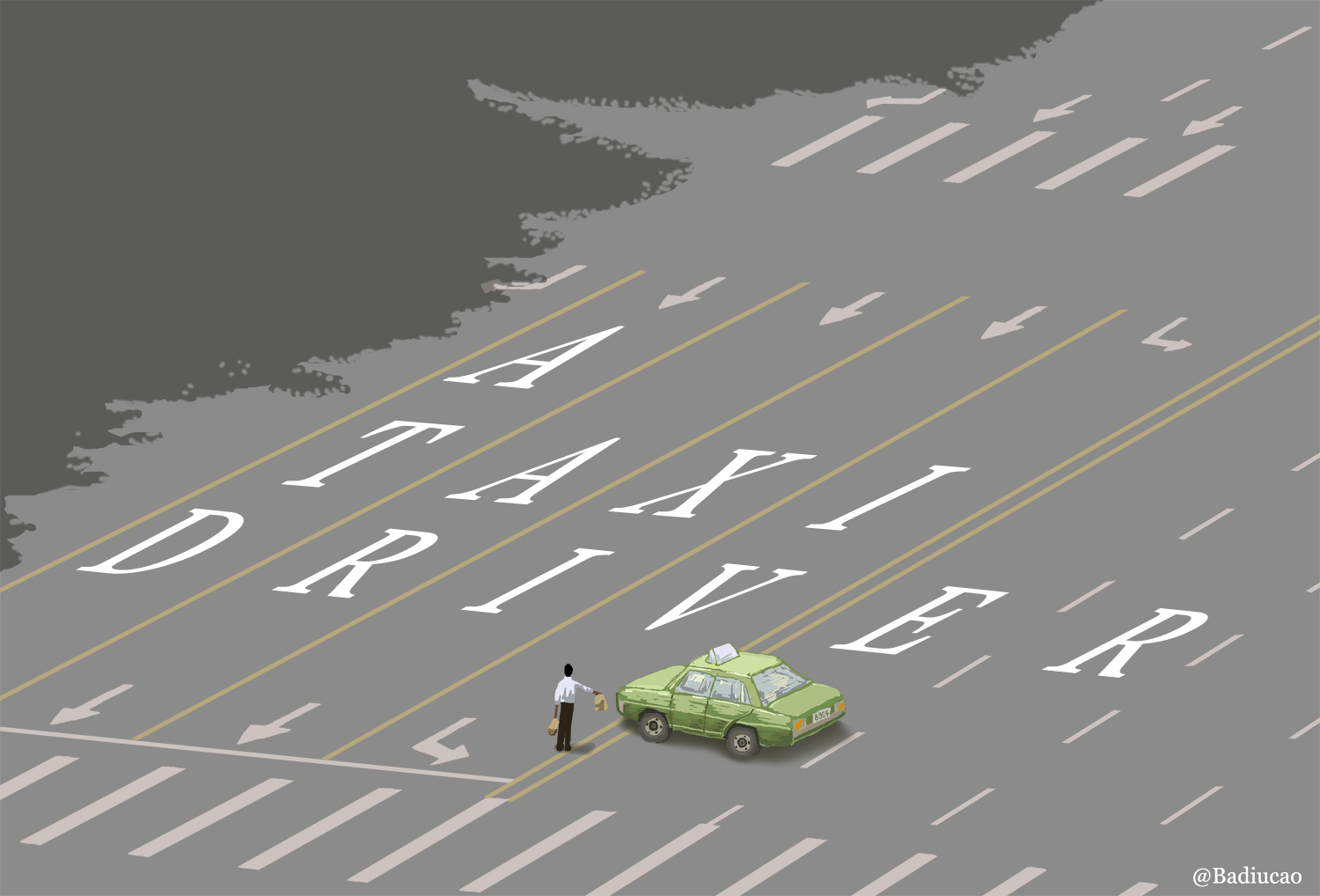

CDT resident cartoonist Badiucao illustrated the parallel between the film’s inspiration and the June 4th crackdown:

A Taxi Driver in 1989, by Badiucao

A Hong Kong Economic Journal article translated by EJInsight’s Alan Lee compares the South Korean government’s relative willingness to allow filmmakers to examine history with the chilly industry climate in China:

The premiere of seasoned mainland movie director Feng Xiaogang’s latest blockbuster, Youth, which was initially scheduled for Friday, Sept. 29, was suddenly called off for screening during the Oct. 1 National Day holiday period.

[…] As the Communist Party holds its 19th national congress this month, it is apparent that the leaders in Beijing are determined to make sure nothing would go wrong during the meeting.

However, in contrast, the recent Korean movie, A Taxi Driver, starring the award-winning actor Song Kang-ho, which is set against the backdrop of the Gwangju Uprising in 1980, has so far become the highest-grossing movie in South Korea this year, and has secured a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film in next year’s Oscars. […] [Source]

Reporting last week on increasing security controls ahead of the 19th Party Congress at Reuters, Ben Blanchard and Christian Shepherd mentioned Feng Xiaogang’s announcement on the delayed screening: “[…A] source with ties to the censors told Reuters that the authorities had considered it risky to screen the film before the congress, as it is partially set during China’s 1979 war with Vietnam – a touchy subject. The fear was that it could spark debate about the morality and necessity of the conflict.”

Further highlighting the contrast between the two governments’ approaches to sensitive historical events, Seoul in 1997 made May 18 a national memorial day, and in 2002 enacted a law privileging families bereaved by the 1980 crackdown. Meanwhile, Beijing continues to “enforce amnesia” surrounding the government crackdown on the 1989 pro-democracy movement.

Chinese netizens have in the past invoked popular Korean historical films to comment on sensitive political events. In 2014, the South Korean film “The Attorney” ()변호인), which told the story of former President Roh Moo-hyun’s time as a human rights lawyer, became a potent allusion to then-detained Chinese rights lawyer Pu Zhiqiang.