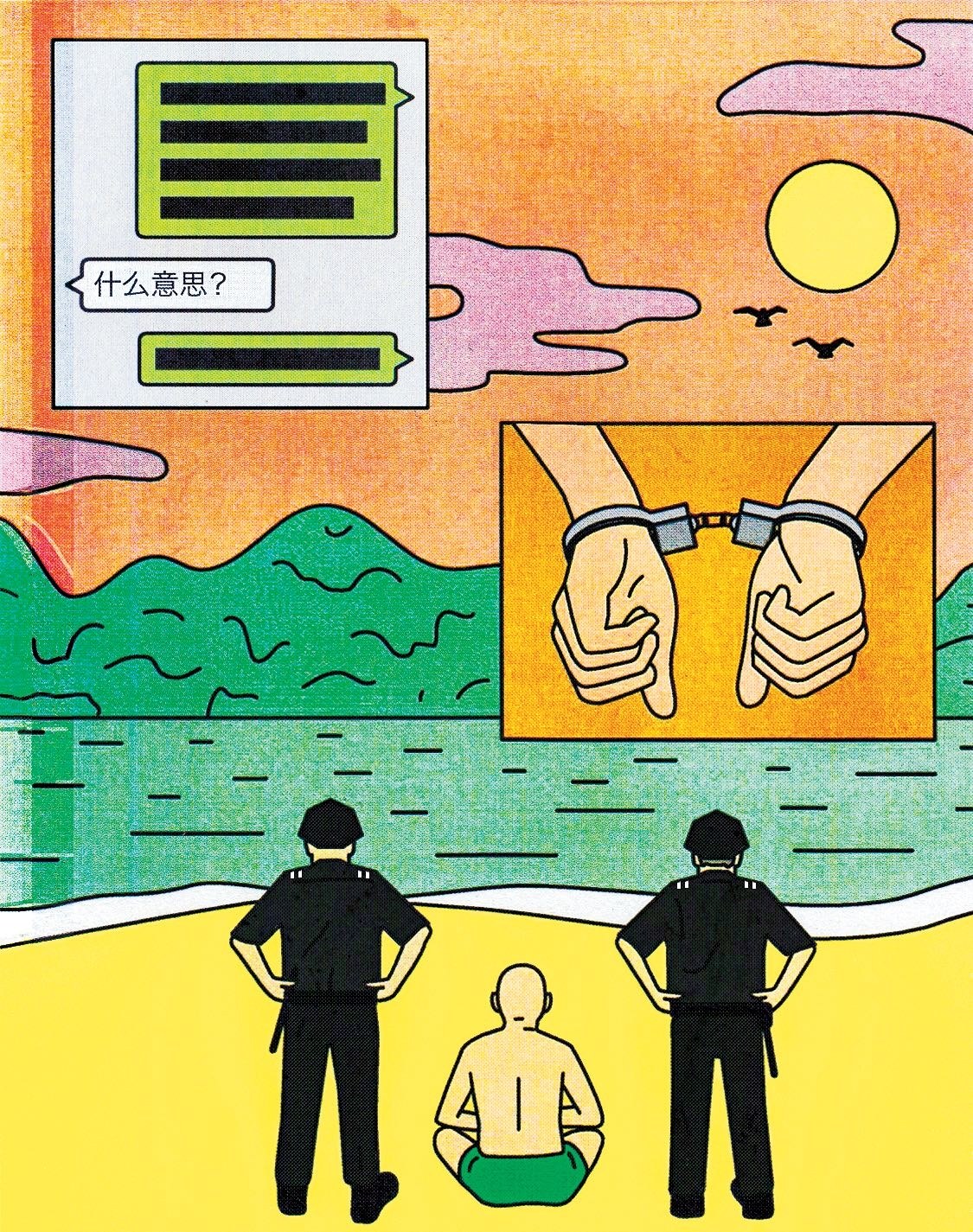

A pair of essays this week illustrates different parts of the spectrum of methods with which Chinese authorities deal with perceived troublemakers. At The New Yorker, Jianying Zha explains the strange phenomenon of “bèi lǚyóu” (被旅游), or “being traveled”: the superficially benign practice of sending people on often lavish but closely supervised vacations to remove them from sensitive areas at sensitive times. This examination frames a profile of Zha’s brother, democracy activist Zha Jianguo, and an account of the chilling political climate under Xi Jinping and “mood swings between bravado, defeatist humor, and gloom” it has stirred among liberal Chinese.

While President Xi Jinping played host to African dignitaries in the Great Hall of the People, the police played host to my big brother at various scenic spots in the province of Hubei, about a thousand kilometres away. A number of other Beijing activists and civil-rights lawyers, including several whom Jianguo knows well, were treated to similar trips. Pu Zhiqiang headed for Sichuan, Hu Jia to the port city of Tianjin, He Depu to the grasslands of Inner Mongolia, and Zhang Baocheng to Sanya, a beach resort on Hainan Island. Kept busy in the midst of natural beauty and attended to closely, they had no chance to speak to members of the foreign media or post provocative remarks online.

This practice is known as bei lüyou, “to be touristed.” The term is one of those sly inventions favored by Chinese netizens: whenever law enforcement frames people, or otherwise conscripts them into an activity, the prefix bei is used to indicate the passive tense. Hence: bei loushui (to be tax-evaded), bei zisha (to be suicided), bei piaochang (to be johned), and so on. In the past few years, the bei list has been growing longer, the acts more imaginative and colorful. “To be touristed” is no doubt the most appealing of these scenarios, and it is available only to a select number of troublemakers. […]

[…] The scheme would seem to be the brainchild of someone who, alert to how lavishly the state will spend on all security-related affairs, figured out a way to creep through the back entrance of the great government banquet hall to join the feeding frenzy in the kitchen. The aim of bei lüyou was plainly to pamper diehard dissidents enough to soften their defiant spirit, but it could also serve as a morale-booster among the rank and file of the security forces. For them, it’s essentially a free vacation that counts as work. In Mandarin, this is called a meichai, a beautiful duty. Jianguo was taken on four such trips between October of 2017 and September of 2018, providing almost a dozen meichai slots for the police. The officers varied as much as the itineraries, and I imagined them haggling over the rotation of these coveted slots. Perks must be shared. Once, Jianguo told me why an elderly policeman was assigned to his team for a trip south: the man was about to retire, and he’d never been to any tropical beaches. [Source]

On Twitter, Human Rights Watch’s Yaqiu Wang re-emphasized Zha’s point that this treatment is exceptional. While Zha writes that it is sometimes used with common petitioners, Wang notes that typically, “to less prominent people, there is more outright brutality. Even [though] Zha is treated nicely, he has absolutely no rights in this situation. We must not forget that.”

In a 2013 op-ed at The Wall Street Journal, CDT founder Xiao Qiang and sinologist Perry Link discussed the “involuntary passive” and other expressions of coded dissent.

This “involuntarily passive” implication has led to a range of other sarcastic uses. One is bei xingfu, which literally means “happiness-ified.” In the Mao era, it was said that the Great Leader mou xingfu (sought happiness) for the people; to be on the receiving end of this search, then as now, is to be bei xingfu. We look at the officials who “represent” us and see ourselves as bei daibiao or “undergoing representation.” In each case, the point is that the “esteemed country” acts upon the “fart people,” not the other way around. [Source]

See more examples in CDT’s Grass Mud Horse Lexicon.

Yet another example, to “be mentally-illed” (bèi shénjīngbìng 被神经病), refers to a bleaker alternative to “being traveled.” At Aeon this week, the University of California at Irvine‘s Emily Baum discussed the historical and ideological background of forceful psychiatric detention in political cases. Baum is the author of “The Invention of Madness: State, Society, and the Insane in Modern China.”

[…] In 2012, the Chinese government released its long-awaited Jingshen weisheng fa, or Mental Hygiene Law. Typically translated into English as the ‘Mental Health Law’ to coincide with international conventions, the content of the document resonates with the goals of the earlier mental-hygiene movement. Though promising to protect the rights and interests of psychiatric patients, it mainly highlights the need for interventionist state policies to identify and prevent mental illnesses. Through an interlocking grid of regulatory and surveillance mechanisms, including schools, businesses and government agencies, the law proposes to mobilise social forces to solve the various dangers associated with psychiatric disorders.

[…] Mental hygiene under Chiang Kai-shek never reached the breadth of influence he envisioned. But while it was slowly abandoned in other parts of the world, its legacy endured in China. The Chinese Communist Party, which rose to power in 1949, continued the practice of associating ideological nonconformity with mental illness. Particularly during the trauma of the Cultural Revolution, when asylums were emptied and political bureaus shut down, those deemed ‘mad’ were closely linked to those deemed counter-revolutionary. In more recent years, too, political dissidents have been accused of mental illness and institutionalised against their will, while in the autonomous region of Xinjiang, re-education has become the tool of choice to heal the ‘madness’ of so-called religious extremism of the largely Muslim population.

The enduring appeal of mental hygiene in China, then, can be attributed to the way it satisfies the ongoing political desire for conformity and control. Just like the Nationalists before them, the Chinese Communist Party has seen in mental hygiene a way to rehabilitate (or merely eliminate) those who have strayed from the ideal of order that modernity had promised. Therefore, the main irony of Chinese mental hygiene is that, while political psychiatry was originally aimed against supporters of communism, the communists would later become its most notorious advocates. And while mental hygiene, the world over, was originally conceived as an opportunity to improve the lives of those considered mentally ill, the vicissitudes of history turned the endeavour almost completely on its head. [Source]