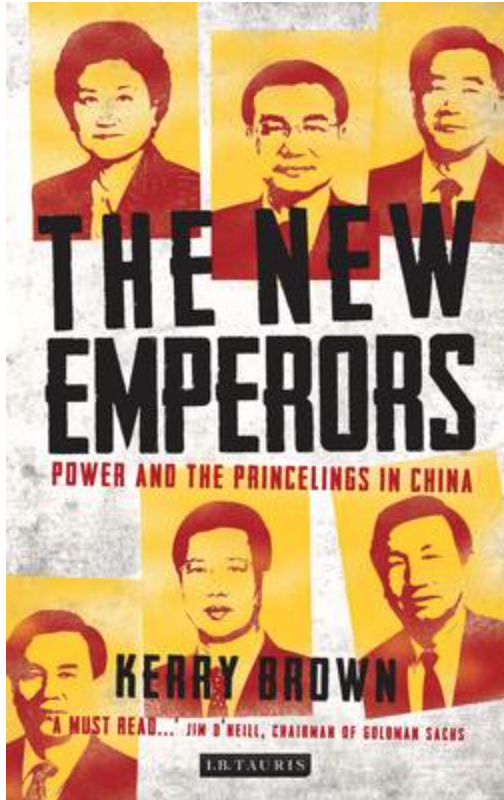

In The New Emperors: Power and the Princelings in China, the University of Sydney’s Kerry Brown offers insight into the lives and thinking of China’s ruling elite. Reviewing the book, The Financial Times’ Jamil Anderlini commented approvingly that “those who have not spent a significant amount of time trying to peel back the carefully drawn masks of the leadership cannot appreciate just how hard this is.” At the University of Nottingham’s China Policy Institute Blog on Friday, Brown mapped the apparent political landscape of the ruling Politburo Standing Committee, and asked how far these murky appearances reflect reality.

Do Chinese leaders have to believe anything? After all, unlike their western counterparts, they don’t have to engage in battles over ideas and approaches during an election campaign, nor are they rudely exposed to forensic intellectual examination in the way that politicians in the US, Europe or other democracies are when they stand for power. The Communist Party of China exists almost to give them a ready made body of ideas that everyone assumes they buy into without too much internal self reflection. In the West, anyone starting out in politics has to at least, at the start, decide whether they are left, right or centrist. In China, if you go into politics then there is one valid choice. The only real issue is whether or not you go into politics, not what you believe if you do so.

[…] In a world where so much is controlled, managed and concealed, Chinese leaders give very few clues about what lies behind the masks they wear. Perhaps the masks are all that really exists, and there is no real inner conviction necessary. But I suspect that this is not the case. The Communist Party of China and its current structures of power are highly specific, in some details, but there is still a strong role for the universal qualities of ambition, animosity, fear, anger and the other passions we see in politics across geography and history. Xi is proving to be an interesting leader because there is this hint lurking behind his public persona of someone who is prone to these emotions. He seems to have strong likes and dislikes, and takes risks propelled by these. Unlike Hu Jintao who practiced self mastery to such an extent it became a self abnegating art form, Xi’s image is not so placidly controlled. And with the pipeline of major issues demanding tactical decisions in the coming months and years, we are likely to see more and more into Xi’s inner world as China enters a period when the raft of core decisions the leadership will have to make means that conviction politics of a former age starts to make a comeback. [Source]

If the leaders’ ideological positions have been unclear, Brown has argued previously that their other political motivations may be less so. Increasingly prominent among these, he suggested, are family interests:

Seeing China as a place where leaders drum the beat of national greatness while at the same time they are prosecuting campaigns for their clan and tribal interests helps us to make a little more sense of the complexity and ambiguities in the way they speak. Their motivations and promises point in two directions – abstractly to the grand society in which they sit at the top, but more concretely to their own network of interests, the most crucial of which are family ones. [Source]

At publisher I.B. Tauris’ blog, Brown recommends five books on modern China’s economy, politics and society which he found useful in writing The New Emperors. The theme of China’s leaders and their behavior and motivations is also present here:

China in Ten Words by Yu Hua, Pantheon Books, New York, 2011

[…] China in Ten Words does as it promises, maps out a world of attitudes and feelings about the country now as it becomes wealthier, more confused and more complicated and complicating. From

people’ toleader’,revolution’ andcopycat’, Yu Hua uses his personal experiences to question some of the key discourse of the country as it stands now. Who precisely are the people, and who are the leaders, he asks, and how do they relate to each other. And why is it that in a China infected by almost universal cynicism and libel, only the core group of the elite leadership is protected from all of this while the reputation of everyone else is fair game for calumniators. For those who are starting to suffer the inevitable side effects of confusion that any meaningful encounter with China and its daily lived reality engenders, this book is a wonderful antidote, administering the sole known cure – coruscating wit and humour.No Enemies, No Hatred: Selected Essays and Poems, Liu Xiaobo, Belknap, Harvard, 2012

Liu is most famous for his incarceration and then sentencing in 2009 for his role in the Charter 08 demand for more freedoms and democracy in China, and for his being awarded the Nobel Prize in 2010. […] Liu’s essays on the world of cadres, where public authority gets mixed up with personal gain, and where the world shifts from the offices and meeting rooms of the day to the nightclubs of excess of the night is forensic, often very funny, but in the end deeply challenging. His guiding question of what, in the end, the real aim and aspiration of the Chinese Communist Party and of the people might be is a haunting one. This book is an eloquent reminder of why the authorities were so keen to silence Liu by incarcerating him. [Source]