The news of imprisoned Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo’s late-stage liver cancer last month sparked many international expressions of support but, as many critics have noted, little concrete action. Since his subsequent death under police guard in a Shenyang hospital, many observers have asked what his case implies for the West’s mounting reluctance to confront China on rights issues and fading international support for China’s already demoralized democracy and rights activists. In the wake of Liu’s death, activist Hu Jia accused Western countries of adopting “a policy of appeasement,” while Princeton-based rights lawyer Teng Biao has warned that “if the West is reluctant to anger China, there will be no hope.” SOAS’ Steve Tsang discussed the situation in an interview at Chatham House:

We haven’t seen any major Western country come out to strongly and clearly hold the Chinese government to account over Liu Xiaobo’s human rights situation. A few leading governments have asked for Liu Xiaobo’s widow to be allowed to choose to stay or leave China. But so far there is no indication of any government backing that up with anything concrete.

That is very weak support for human rights in China. And it reflects a new reality: of the unwillingness of leading democracies to challenge the Chinese government on human rights matters, and the confidence on the part of the Chinese government to simply ignore what the rest of the world may think about it.

[…] You can ‘engage’ in the sense of raising the issue with the Chinese authorities, as indeed the UK government and the German government have done, for example. But they haven’t actually taken any concrete steps.

The type of engagement where Western governments would get the Chinese government to demonstrate that something concrete was being done to improve the human rights situation – that era has gone. It is not going to come back in the foreseeable future. And therefore, the situation in terms of human rights in China will not be improving in the foreseeable future. [Source]

Tsang argues that the global leadership vacuum left by Donald Trump’s election in the U.S., and the consequently “stronger expectation and desire to see China playing a global role,” is behind much of the recent increase in reticence. But a recent report on the issue by The New York Times’ Chris Buckley suggested that this had only accelerated an existing trend:

“It’s certainly become more difficult,” said John Kamm, an American businessman and founder of the Dui Hua Foundation, who for decades has quietly lobbied China to free or improve the treatment of political prisoners. He said his attempts to win approval for Mr. Liu to leave China for treatment, as Mr. Liu and his wife requested, got nowhere.

[…] Still, Mr. Kamm and others said the shift came many years before Mr. Trump entered the White House in January.

“I do not think that the world prior to Jan. 20, 2017, was one rife with robust, consistent diplomatic intervention on behalf of peaceful, independent civil society in China,” said Sophie Richardson, the China director of Human Rights Watch. “Taken together, particularly over the 2000s and into the 2010s, you have got progressively less interest on foreign governments in really fighting as hard as they ought to have for systemic change in China.”

[…] The shifting geopolitics around China and the human rights issue also appeared to be reflected in the disjointed reaction to Mr. Liu’s death from top officials of the United Nations, where China has moved to raise its prominence by increasing financial support and furnishing peacekeeping troops. [Source]

At The Nation, Trinity University’s Gina Anne Tam and UC Irvine’s Jeffrey Wasserstrom examined the tension between China’s shifting role on the global stage and its handling of local opposition such as Liu Xiaobo and Hong Kong democrats:

In mid-January, when Xi Jinping made his debut at Davos, the head of the Chinese Communist Party and president of the PRC took pains to appear as a self-confident leader determined to guide his country into a high-tech, globally interconnected future. He wanted the world to think that China had put far behind it the century of oppression by foreign powers that preceded the founding of the PRC, during which time, so goes the national myth, the country had been poor, weak, and badly governed. He wanted, too, to show that China had moved on from the ideological upheavals, irrational personality cult, and global isolation that characterized much of the era of rule by Mao Zedong (1949–76). This image of Xi, taken at face value in some international press reports, has stayed in the news via reports of such things as his championing of the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, presented as a 21st-century reboot of China’s economic integration with the global community.

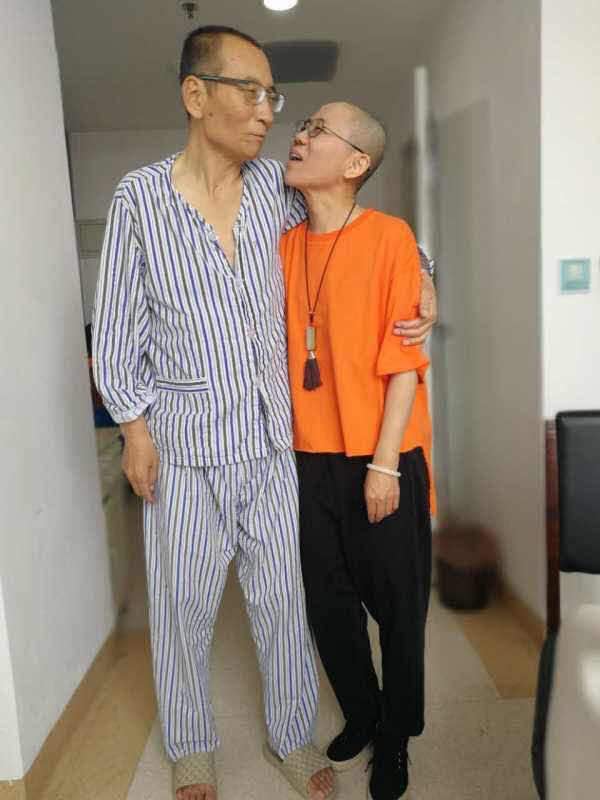

Recently, however, we have seen abundant and dispiriting evidence that there is a second, very different Xi to reckon with—one who wants to close off rather than open up China and who heads a government that makes moves eerily reminiscent of those associated with dark parts of the Mao era. Six months after the first Xi made headlines in Davos, this second Xi was refusing the requests of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Liu Xiaobo to receive life-saving treatments overseas, leaving him to die a prisoner of conscience. The first Xi speaks of global human rights, but the second has overseen an escalation of Internet censorship that has reached new extremes in the wake of Liu’s July 13 death, and, in a throwback to the guilt by blood-and-marriage ties that characterized the Cultural Revolution, he continues to persecute the prisoner-of-conscience’s wife, Liu Xia. [Source]

In a ChinaFile Conversation following Liu’s death, Jocelyn Ford noted silence on Liu’s case at the World Economic Forum’s nearby “summer Davos” meeting.

While China’s growing global status discourages criticism from abroad, it also, as Tsang noted, gives both its government and its public greater confidence to rebuff such challenges when they do arise. Andrew J. Nathan argued at Foreign Affairs that “Beijing now simply pays no heed to foreign pressure.” At East Asia Forum, Kerry Brown wrote that Liu’s case in particular had become emblematic of this new boldness:

The Chinese state often talks about win-win outcomes. In the case of Liu, it has turned out to be lose-lose. No one comes out of this happily. For Liu, his family and friends, the situation is a terrible tragedy. For the Chinese government — which will be blamed for the entire situation — it is a great stain on its reputation.

[…] When reflecting on the meaning of Liu’s case, why was it that every step of the way, right to the end, the Chinese government did not compromise, despite paying a huge price in terms of its reputation and image? Since the 2008 Beijing Olympics, the Chinese state has poured huge resources into promoting itself abroad. Under Xi Jinping, it has made a concerted effort to communicate the ways in which its role in the world is now beneficial and positive. Yet this one case gave its most implacable enemies endless ammunition.

[…] Liu became for Chinese officials a symbol of how they would not bow to Western pressure and a test case for how emboldened they felt in the face of criticism about their rights record. Hence, the refusal to allow him to attend the Oslo ceremony — and the empty seat that was used to represent him — was a powerful and emotive symbol. [Source]

Despite this new climate, many still hope for productive Western action. In an essay posted at China Change, 1989 protest leader Wang Dan suggested that Liu’s death could reverse the trend of international reticence:

[…] Liu Xiaobo’s death will reverberate throughout the international community, emboldening the call to reckon with its policy towards the human rights of the Chinese people. The tragic death of a Nobel Peace laureate, we hope, will prompt those parties and politicians who have cozied back up to China to rethink their relationship.

In other words, Liu Xiaobo’s passing could become a turning point in China’s rise: the CCP, which continues to buy global support with the image of rapid economic growth, must bear the burden of Liu Xiaobo’s death for a long time to come. It will deal a blow to that image and an immense setback for the CCP’s arrogance. We will be glad to see this change, but the price we paid for it was Liu Xiaobo’s life. It is a tragedy of our time. [Source]

NYU’s Jerome Cohen also suggested that Liu’s fate might bring change:

[… A]s some observers have come to recognize, if only as inadequate consolation, the extraordinary circumstances of this Nobel laureate’s departure may prove his greatest contribution to the cause of free speech he so gallantly served. Liu’s final tragedy has alerted the world, to an extent even greater than did the empty chair in Stockholm, to the Chinese Communist Party’s inhumane oppression.

[…] When Liu Xiaobo was treated in the hospital, Chancellor Angela Merkel called upon the Chinese government in vain to release him to go abroad for his final moments “as a signal of humanity”. Can we expect foreign governments to do more? Will they be more effective? Many governments feel that their human rights protests against Beijing will have no positive impact on the PRC and will have a negative impact on other aspects of their relations with China. To the extent they do protest, it is often more a response to their own citizens’ pressure for action than to genuine concern for human rights, and their domestic business constituents usually have more clout than their human rights community. Compassion fatigue and realistic hopelessness about the Xi Jinping regime are also factors.

Yet those of us on the outside have to persist in our efforts to directly influence developments in China and to put pressure on our own governments not only to influence China but also improve their own human rights performance. [Source]

Similarly, from Thomas Kellogg at ChinaFile:

Above and beyond any renewed rights diplomacy undertaken by Western governments, Liu Xiaobo’s passing should lead to a rethink of many of the assumptions that all of us have held about China’s trajectory. It seems clear now that the C.C.P. has fully rejected a moderate reformist path, and instead is moving toward a future in which Party oversight and control is much more encompassing, much more robust. In this context, the role of rights diplomacy by Western governments becomes all the more vital: as Chinese voices face ever greater restrictions, all of us in the international community need to push our own governments to raise concerns with Beijing. The moral obligation to do so has never been more clear. [Source]

In an op-ed at The Washington Post, U.S.-based legal activist Chen Guangcheng urged swift Western action, and raised some possible courses:

It is imperative that the outside world act swiftly and decisively to demand justice for Liu and his wife and to establish new norms in dealing with this violent, cash-flush dictatorship. In doing so, democratic nations need to remember that Western markets are extremely valuable to the CCP. What’s more, Western countries need to bury their anxieties about economic benefits from Beijing, and instead firmly embrace the essential values of freedom, democracy, the rule of law, and human rights that have made America and other Western democracies great, strong and stable.

Time is of the essence.

[… T]he United States and the international community need to demand the unconditional release of Liu’s wife from house arrest, and the freedom for her to live out her life where and as she chooses. If Liu Xia does not get the necessary attention and support from the world, her fate will quite likely follow that of former CCP central party secretary Zhao Ziyang, who was kept under house arrest until his death. Just as the CCP was never going to allow an ailing Liu Xiaobo out of his hospital prison, so it does not want to see Liu Xia in freedom, since she would surely speak out about the truth of what happened to her husband.

The U.S. government has many other tools in its arsenal, including the Global Magnitsky Act, which allows Washington to freeze financial and other assets held in the United States that belong to foreign officials guilty of human rights violations. Washington should use the Magnitsky Act to punish those responsible for Liu’s death. In this case, given Liu’s high profile, the perpetrators are likely in the highest levels of the Communist Party. [Source]

U.S. Senator Marco Rubio highlighted other possibilities in an open letter to Liu Xia, whose current whereabouts are unknown. Chinese authorities claim that she is free, after years of house arrest without charge, but have aggressively repelled efforts to contact her.:

Many Americans and people around the world believe these and other injustices demand accountability. Current U.S. law gives the President of the United States the authority to impose visa bans and to freeze the assets of any foreign citizens who suppress basic human rights; surely the Chinese government’s treatment of you and your husband meets this standard. Other measures, including sanctions, can be brought to bear. I fear that if there is no price to pay for the Chinese government’s treatment of your husband, arguably China’s most prominent political prisoner, it will send a devastating message to thousands more like him, whose names we may not know but whose harassment, imprisonment, deprivation of rights, denial of medical treatment, torture in detention, and more, are daily realities. [Source]

In a different context—that of China’s support for North Korea—Wall Street Journal editorial board member and former George W. Bush speechwriter William McGurn recently suggested that access to elite U.S. universities by young relatives of China’s rulers could be used as a lever.

Rubio chairs the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, which last week requested that the U.S.’ new ambassador to China Terry Branstad “formally invite Liu Xia to the U.S. embassy for a meeting to better understand her current situation and long-term wishes, as well as to provide a space where she is able to speak her mind freely. If such a request is denied, or she is blocked from visiting the Embassy, we ask that you try to meet her at her place of residence.”

While many called for action in support of Liu Xia, Yang Jianli of Initiatives for China pointed out a number of other vulnerable cases in a post at China Change:

Without a doubt, the Chinese communist regime is responsible for Liu Xiaobo’s death. However, the policy of appeasement carried out by democracies towards China’s human rights abuses has made them accomplices to Liu Xiaobo’s slow and stealthy murder. It is a sad and disturbing fact that many leaders of the free world, who themselves hold democracy and human rights in high regard, have been less willing to stand up for those rights for the benefit of others. If the world continues to acquiesce to China’s aggression against its own people, Liu Xiaobo’s tragedy will be repeated, and the democratic ideal and the security of all free peoples will be in jeopardy.

The tragic death of Liu Xiaobo should give all of us a stronger sense of urgency in helping prisoners of conscience of China. It is a legitimate concern that now we can expect more human rights activists will languish and disappear in Chinese prisons: Wang Bingzhang, Hu Shigen, Zhu Yufu, Ilham Tohti, Tashi Wangchuk, Wang Quanzhang, Jiang Tianyong, Tang Jingling, Wu Gan, Guo Feixiong, Liu Xianbin, Chen Wei, Zhang Haitao… the list goes on. If American advocacy for human rights and justice is to mean anything at all, the U.S. government must do more to support these political prisoners and to hold accountable the Chinese government and individuals who so brazenly abuse the fundamental rights of its people. [Source]

Much of the blame for the weakness of foreign support for Liu has been directed at Western governments, but Robert Precht wrote at Justice Labs about the failings of NGOs, arguing that their outdated educational programs may inadvertently have stoked official suspicion of foreign and domestic civil society. Precht goes on to suggest how Western businesses and educational institutions should take up the cause of human rights in China:

The fate of Liu Xiaobo spotlights the failure of Western human rights groups working in China. President Xi Jinping’s campaign against dissent has been successful. The civil society movement Liu helped to motivate is in disarray. “In the last seven years, he’s been forgotten,” said activist writer and friend Yu Jie, “I think we were overly optimistic.” Partially responsible for this unjustified optimism are the scores of foreign NGOs that opened offices in the country and promoted the idea that with the proper education, over time the Chinese would start to embrace western human rights values. This approach was ineffective, and it also hobbled the development of domestic civil society in China. New strategies are needed, particularly enlisting Western businesses and universities to universalize the human rights message.

[…] Adopted in 2011, the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights recognize the critical role businesses play in protecting human rights. According to the Guiding Principles, an enterprise’s corporate responsibility entails making a clear and public policy commitment, implementing due diligence processes, and providing or cooperating in the creation of remedies for human rights violations committed by their business partners. In the China context, this would mean that businesses need to make public commitments on their websites to uphold human rights, to engage in meaning due diligence to identify the risks to human rights if the businesses partner with the Chinese government on any projects.

If companies and universities adhered to the Guiding Principles it would be less likely that the world community would forget about such people as Liu Xiaobo. Foreign NGOs that may no longer be able to work inside China as a result of the new NGO law can still make a vital contribution. They should come together and develop a strategy for engaging the business world in making China a more just place. [Source]

One course that will not work, journalist Chang Ping argued in the ChinaFile Conversation, is the “quiet diplomacy” traditionally popular among Western governments reluctant to confront China in public.

Apparently, rescue efforts for Liu employed the traditional “quiet diplomacy” approach. This approach set itself up for failure and only humiliated Liu’s would-be rescuers. I recently wrote about this phenomenon in Chinese.

In my article, I introduced a book published in 2014 by German scholar Katrin Kinzelbach: The EU’s Human Rights Dialogue with China: Quiet Diplomacy and its Limits. Kinzelbach tracks human right dialogues between the E.U. and China from 1995 through 2010, by examining a variety of documents including internal memos and by interviewing many stakeholders covering more than 20 U.N. member-countries and all former and current chairs. The study concluded that “quiet diplomacy” has had only a very limited positive influence on China’s human rights. It not only failed to achieve its expected goals, but also made the Chinese government trample human rights more overtly, treat human rights conversations as perfunctory, and even counter queries, criticisms, and suggestions. Two weeks ago, 10 human right organizations including Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Civil Force, The International Campaign for Tibet, Human Rights in China, International Service for Human Rights, and The Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization published a joint statement, calling on the E.U. to pause its human rights dialogues with China. “Instead of a forum for promoting rights, the EU-China human rights dialogue has become a cheap alibi for EU leaders to avoid thorny rights issues in other high level discussions,” the statement said.

The Chinese government would rather the entire world watch Liu Xiaobo dying in its hands than give him even a tiny amount of freedom and the chance to live a little longer. This is new evidence that “quiet diplomacy” has failed. It shows the degree to which, when leaders of the Western developed countries fear the Chinese Communist Party, they too abandon the principles of modern civilization including human rights, freedom, and democracy, making their secret diplomacy nothing more than an act of public self-humiliation. I hope the death of Liu Xiaobo wakes them up. [Source]