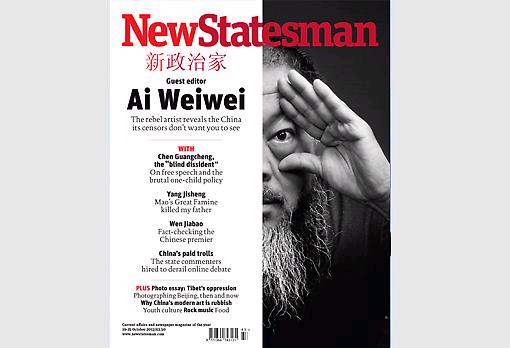

Dissident artist Ai Weiwei served as guest editor and appears on cover of the latest issue of British magazine New Statesman, in which he leads with a challenge for China to re-evaluate and recognize its position in the world as it seeks answers to the many problems it faces:

The future of China is uncertain. I believe that the world is becoming a better place, largely thanks to advances in technology which help us to address so many of the problems that we face. The expanding use of social media and the internet will help China become a more conscious and intelligent country, but the future remains uncertain. There are problems ahead which we can’t even identify yet, and it is vital to be prepared and to meet these challenges in every way we can.

Whatever the future problems are, I believe that, both as an international society and as an individual, you have to see the human problem as one. We share this planet and we have been divided for too long, for ridiculous reasons. Now, we have to come together and say, as one, that we share the same values, that we can respect differences and that, together, we can create the best possible solutions.

If I have one message for you, the readers of the New Statesman magazine, whether you are reading this in English or in Mandarin, on the page or online, it is this: the only way we can be successful, in China and in life, is through greater communication and wider awareness, in constantly questioning our standards and our conditions. You, as readers, are part of this, you are active members of this family, and you can be proud of that.

Ai, who placed third in ArtReview’s 2012 ranking of the most powerful figures in the art world, becomes the eighth guest to edit the New Statesman. The magazine’s features editor, Sophie Elmhirst, details the story behind Ai Weiwei’s role:

Ai Weiwei agreed to guest edit the New Statesman in April this year. We had sent the invitation to him six months earlier via his London representatives, the Lisson Gallery, but, understandably, it took him a little while to respond. Last year, Ai spent 81 days in detention. An artist already renowned for his work and fearless irreverence towards the Chinese authorities became a global cause when he was arrested at Beijing Capital Airport and detained in a secret location. Given the level of international attention and the ongoing pressure on Ai even after he was released (he was quickly filed with a £1.5m fine for tax evasion), it seemed unlikely that we would hear back from him. But then, suddenly, he said yes.

Looking back, that out-of-nowhere yes makes more sense than it did at the time. After spending a week with Ai at his studio in Beijing, I learned that he likes to do things on instinct. The more unexpected an opportunity, the more attractive it is to him, especially if it offers a platform for challenging the Chinese government. And when he says yes, he means yes.

…

Over a week in Beijing I met with Ai almost every day and his team – a group of highly talented and motivated photographers, organisers and writers in their own right – pitched a stream of ideas. We could have made a book: the challenge was to edit down the material into a series of pieces that could fit into a magazine. And there was another test too: language. The vast majority of this issue of the New Statesman – for the first time in its history – was written originally in Chinese by Chinese writers, activists, academics and artists. After I returned from Beijing and had firmed up with Ai and his team which article commissions, photography essays and interviews were going to be included, we started, slowly but surely, to receive the copy, which had to be translated into English and then edited in both languages. The plan from the start was to produce the issue in both Chinese and English (see deputy editor Helen Lewis’s account of distributing the Chinese version behind the “great firewall”). Usually we produce one magazine a week; this time it was two, with one version in a language that no one in the New Statesman office could speak, read or write. But with the help of translators, Chinese friends, Ai Weiwei and his team we got there in the end.

New Statesman also produced a digital PDF version of this week’s issue in Chinese, which it uploaded to file-sharing sites in order to circumvent a censorship regime that has “tried to obliterate the existence of Ai Weiwei from the internet”. From an essay about censorship by former newspaper editor and secret detainment victim Cheng Yizhong, to an interview Ai conducted with a paid internet troll charged with disrupting netizen debates, deputy editor Helen Lewis promises Chinese readers they will find “a story very different from the one they are told by the state-controlled press”.

See also previous CDT coverage of Ai Weiwei, including an interview he gave to German magazine Der Spiegel earlier this month.