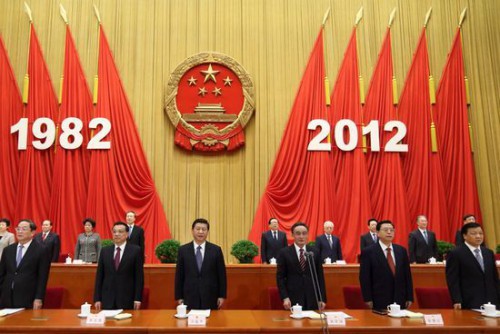

At China Media Project, David Bandurski argues that “there is now little doubt that the defining ideological debate in China this year will be that between constitutionalism and socialism.” He traces the issue back to last year’s celebrations of the 30th anniversary of the Chinese Constitution, in which Xi Jinping strongly endorsed the authority of the constitution and law:

Right on the heels of Xi Jinping’s speech, it became clear that political reform advocates in China were drawing strategic inspiration from Xi’s remarks, that they saw “firmly establishing the Constitution” as the ideal moderate strategy to push change on the basis of a document that already — or so they argued — constituted and represented a political consensus.

The Southern Weekly incident in January 2013 and the year’s inaugural edition of the journal Yanhuang Chunqiu(“The Constitution is a Consensus for Political Reform“) were a throwing down of the gauntlet.

[…] By late spring and early summer, the counterattacks against constitutionalism as a new way of framing the political reform debate had become relentless.

[…] Most recently, there were three editorials in the overseas edition of the Party’s official People’s Daily, all issuing colorful attacks on constitutionalism (one likening it to “trying to catch fish in the trees”). The first of these editorials baldly declared: “Constitutionalism only belongs to capitalism, and it is not compatible with socialism” (宪政只属于资本主义,和社会主义无法兼容.). [Source]

Bandurski also relates several less well-known voices who have written on the issue.

The article coincides with China Media Project’s rerelease of Heralds of History (历史的先声), “a book that documents the articles and speeches that defined the Chinese Communist Party’s push for freedom, democracy and constitutionalism in the 1940s.” He includes some excerpts from the book which will be surprising to many:

The book, edited by CMP fellow Xiao Shu (笑蜀), was first published in China in 1999, but was quickly banned by the authorities. It is an authoritative collection of speeches and articles outlining the CCP’s core goals and political beliefs from the early 1940s through the end of the war of resistance against Japan in 1945.

For example, there is Mao Zedong’s June 13, 1944, article in the Party’s Liberation Daily, in which the first paragraph from the “great helmsman” reads: “China has shortcomings, many shortcomings in fact, and the greatest of these, in a word, is that it lacks democracy. The people of China are in dire need of democracy, because only with democracy can our war of resistance have strength, can our internal and external relations be right . . . can we build a good nation — and only democracy can ensure unity in China once war has ended.” [Source]

The CMP post also includes a review of the book by Wu Wei (吴伟), a scholar of modern Chinese history, who explains the book in the light of the recent constitutionalism versus socialism stoush.

Further exploring the issue, and suggesting some possible future developments in the debate, The Economist’s Banyan blog writes:

The stridency of the tirades in the press suggests not all is sweetness among the leaders. As they paddle on the beach at Beidaihe, they are unlikely to bicker about constitutional law. They will, however, be squabbling over personal power and policy. One possibility is that Mr Xi and his allies are preparing a radical set of economic reforms: freeing interest rates, overhauling local-government finances, and easing landownership and residence rules. Stressing the primacy of the party and attacking abhorred liberalism in its latest disguise—constitutionalism—may help Mr Xi to push through his economic agenda over the objections of hardliners and interests threatened by reforms.

Still, little suggests that Mr Xi objects to the political line of the anti-constitutionalists. Mao Zedong followed Marx in believing that the economic structure determines the political one—a view echoed by many Western analysts today who argue that China’s politics has to change to reflect its economic transformation. By contrast, Deng Xiaoping and his successors, down to Mr Xi, have argued that to ensure that economic development does not lead to instability or chaos, strong party rule is more imperative than ever. For the People’s Daily, the Soviet Union’s collapse offers a salutary lesson: Mikhail Gorbachev “was thoroughly defeated because he used Western constitutionalism as a blueprint”. [Source]

Read more about China’s constitution and socialist ideology via CDT.