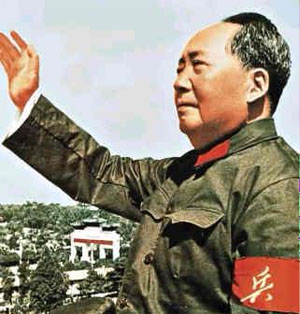

With the 120th anniversary of his birthday just passed, much ambivalence exists amid the Chinese public and Communist Party regarding the legacy of Mao Zedong, and China’s state media did much to reinforce the long-standing Party maxim that Mao was “70 percent right and 30 percent wrong.” Exclusive commentaries published by foreign media outlets, however, focused in on some of the darker aspects of Mao’s legacy. In an op-ed for the New York Times, pro-democracy activist and Human Rights in China senior policy advisor Gao Wenqian surveys Mao’s legacy, describing the “cult of Mao” as China’s “greatest obstacle to social transformation”:

It’s no surprise that China’s leaders have chosen to honor Mao with such pomp. In the decades following the establishment of the People’s Republic in 1949, Mao’s cult of personality formed the cornerstone of the one-party system. Under the next paramount leader, Deng Xiaoping, the cult of Mao moderated, and limited criticism of his worst disasters was permitted. Chinese rule became more consensus-based: by no means democratic, but guided by the Politburo Standing Committee rather than a single person’s whims. But now, as the economy has slowed, China’s leaders have found it necessary to defend the Community Party’s monopoly on power by invoking the nation’s “glorious” history — with Mao’s legacy its most potent tool.

It is certainly not taught in textbooks, but Mao’s record was nothing short of a disaster: The Great Famine of 1958-61 — the result of a course of industrialization known as the Great Leap Forward — caused starvation not seen on a scale since Stalin’s collectivization. Meticulous research by the journalist Yang Jisheng and the historian Frank Dikötter has estimated the death toll at anywhere from 36 million to 45 million. [Source]

Radio Free Asia published a commentary on Mao by Bao Tong, former CCP Central Committee member who has spent most of his days since June 4, 1989 in detention. Bao wrote the essay, which seeks to overturn the “myth of Mao Zedong,” from under house arrest in Beijing:

The 20th century saw three great political myths. The myths of Hitler and Stalin have been annihilated, but the myth of Mao Zedong still haunts China today.

It won’t be hard to give a comprehensive evaluation of Mao Zedong, so we can get a clear picture of what he actually achieved.

[…] Some people credit Mao with “founding” China, as if China wasn’t a country, or didn’t exist before that, as if the people should be grateful for having a country at all, regardless of what that country achieves. However, I won’t dedicate much space to that debate here.

There are others who credit Mao’s great and mighty policies with getting “the Chinese people to stand up.” Perhaps they mean that it’s a matter of wonder that the Chinese people were able to stand up at all in the mess that he got the country into! […] [Source]

Also see prior CDT coverage of Bao Tong, who once served as political secretary to Zhao Ziyang.

In an interview with The Atlantic, 92-year-old South Carolina native and former CCP member Sidney Rittenberg reflects on the late CCP Chairman:

When did you actually first meet Chairman Mao in person?

It was October 20-something in 1946. I’d just come over land to Yan’an [the Communist Party home base in Shaanxi Province] from Inner Mongolia, and after arriving, I was immediately taken to the weekly dance in the Party headquarters building. When we opened the door to go in, Mao was dancing in the middle of the floor. He saw me and stopped dancing, and after I shook his hand he said, “We’d like to welcome an American comrade to join in our work.” Then, he took me over by the side of the hall and sat me down on a chair, and immediately said that he wanted to invite me to his place and spend a day or two just talking about America. The interesting thing here is—and this is confirmed by Li Zhishui, the doctor who wrote the book on Mao’s personal life—America was the only foreign country that really fascinated and interested him and was one he greatly admired. He would invite left-wing Americans to his place and sit and chat. To my knowledge, he didn’t invite foreign experts of any other nationality—just the Americans.

[…] What were your impressions of him? What was he like? Was he as charismatic as people say?

He was only charismatic because of the strength of his mind and his ability to put complicated political thinking into very colorful, popular language—which is a talent that seems to be totally lost in China these days. But, you know, he was no Fidel Castro. He was no orator. He didn’t keep people spell-bound—he was a rather slow and bumbling speaker. But the way he analyzed things was fascinating. And he was always careful to make it very simple, to put things in popular terms, not like the mind-numbing stuff that began coming out later.

You know, it was interesting: When you sat and talked with him, he was laid back. He talked as though everything was just a casual conversation and very humorous. Anyone who was talking with him in my experience would be constantly in stitches laughing, and he’d laugh too. So he gave the impression of a kind of sage from the backwoods, who was a great analyzer and a great talker. Nothing threatening at all, nothing tough. […] [Source]

Click through to read the full interview with Rittenberg. Also see prior CDT coverage of this rare American member of the CCP who spent over 15 years in solitary confinement in China.