Badiucao recently joined CDT as a contributing cartoonist. The artist, who currently lives in Australia, is one of China’s most popular and prolific political cartoonists, and he confronts a variety of social and political issues head on in his powerful work. See the drawings he has done for CDT so far, and more of his work on his website. He also posts his drawings to Twitter and Google+.

In an effort to allow CDT readers a chance to get to know him better, I asked him a few questions about his life and work. I have translated his answers from Chinese. Please stay tuned to see more of his work on CDT in coming months.

CDT: Can you give us some idea of your childhood and upbringing? What was your family like, what kind of work did your parents do, and what kind of environment did you grow up in?

Badiucao: I was born in Shanghai and grew up in the city in the 1980s. Because I was in Shanghai, my childhood had many advantages over Chinese people in other places. I’ve always enjoyed the privileges and conveniences of a big city (for example, education and healthcare).

But I also experienced my family’s financial ups and downs, in the midst of the country’s wave of reform. In a dual-career household, when my mother was laid-off we went through a period of turbulence. My impression is that after my mother left the more relaxed job in the state-owned sector, she ran all around looking for a new job and then spent two hours a day on the bus to go far from home to work as a cashier and would come home exhausted.

On the other hand, in terms of social awareness, my father became my most important influence. But this starts from my grandfather. My grandfather was the first generation of Chinese filmmakers, and was persecuted after the founding of the People’s Republic of China and sent to a farm for re-education through labor in Qinghai during the anti-Rightist campaign. Finally he starved to death in a strange land when my father was just a child. A few years later, my grandmother died of illness on New Year’s Eve, and my father became an orphan. Fortunately, his neighbors helped him. When he grew up he worked hard to apply to college, but because of his family background he lost his opportunity for admission, which caused him a lifetime of regret.

As I grew up, my father would sporadically tell me stories of our family history, but his narrative very seldom contained any hatred. More often, it was fear and helplessness. The fear comes from political tyranny; the helplessness is from the fate of impermanence. He always warned me not to participate in any political activities and not to express my own opinions. He also did not encourage me to study and work in the arts. He hoped I would become an engineer or scientist, because he thought that in China, science and technology are relatively safe professions. He thinks anything related to ideology has the possibility of being grabbed by the tentacles of politics and thrown into a black hole, as was his father’s experience.

But it was very clear, because of too many requests, rebellion began to brew inside me. The more I was urged and exhorted not to do something, the more it was worth the risk. I love art! If my father did not want me pursuing study or work in the arts in China, then I would go abroad. Of course, my parents supported me going abroad. They also thought that the “hidden dangers” in my personality could only be relieved by leaving China.

CDT: You currently live in Australia. What’s your day job? How long have you lived there and how do you like it?

BDC: My current job is a kindergarten teacher. When I am together with children, I feel my soul is deeply relaxed. Also, in different education systems, I feel the beauty of the respect for freedom and for the individual.

I have been in Australia for four years, and I really enjoy the local scenery and food. More important is experiencing the enthusiasm and respect for the arts. Soon after I arrived, with the help of a teacher, I was able to sell my photographs at a small gallery, which gave me great encouragement and confidence.

I also really appreciate Australia’s social protections and education benefits, which gave me the opportunity to use a federal loan to attend art school. Of course, citizens’ right to vote and the unrestricted Internet are really great.

CDT: When did you first begin drawing political cartoons? Have you ever been formally trained as an artist? Did you ever draw while you were living in China and if so, did you ever fear (or suffer) any consequences?

BDC: I started drawing political cartoons after I came to Australia. My first drawing was about the 2011 Wenzhou high-speed train crash. Before I started drawing cartoons, I had no formal art training.

When I was in China, I never drew political cartoons, and very seldom drew at all. My main artistic activity was taking photographs, and I was a lomography [analog photography] hobbyist.

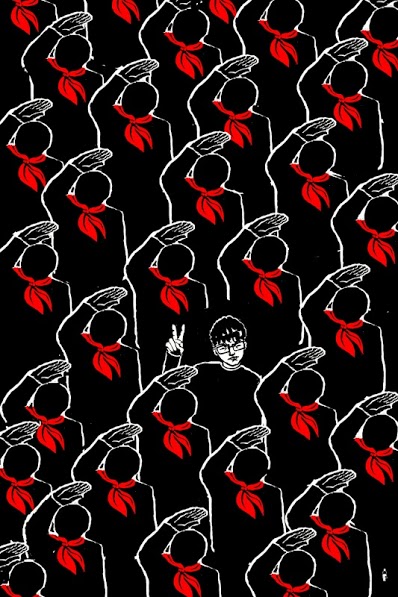

CDT: Your work has a very distinctive style, using mostly strong lines and red and black. How did you develop this style? What writers or artists have had an important influence on you?

BDC: In my view, if you open the dazzling neon jacket, China’s complexion is nothing more than black and red. Red is blood, fear and violence. Black is iron, freezing nights, depression, despair, and the silent corners. It’s the cloth gag covering the screams. The country is like a giant meat grinder, a layer of fresh blood covering a layer of despair, new despair covering the layer of fresh blood, over and over again.

The biggest stylistic influence on my work is German printmaker and sculptor Käthe Kollwitz. She was a despairing mother, caught in the vortex of blood and iron, who drew arms to protect her frightened, helpless children. She is the most powerful woman I have ever seen. She makes me think of my mother. Another is the works from the “black period” of Spanish painter Francisco Jose de Goya. But Ai Weiwei’s artwork and documentary have shaped my perspective on courage and on observing China. His personal experience and civic investigation work and art work have played an irreplaceable role in my understanding of the realities of contemporary China.

In literature, the late Chinese writer Shi Tiesheng’s “Notes on Principle” is the piece of Chinese literature that has had the biggest influence on me. In foreign literature, Romain Rolland’s “Jean-Christophe” and Alexander Dumas’s “Count of Monte Cristo” also had an important influence on me.

CDT: Who do you consider to be your primary audience? What has the reaction been to your drawings among your contemporaries/friends/colleagues in China?

BDC: My earliest audience was Internet users. They remain my primary audience. They give me the power to continue creating. The biggest group among those are the so-called “reincarnation party” on weibo. With Internet censorship, our accounts are often prevented from publishing or are even deleted. My Sina Weibo account has been closed more than 30 times, and many of my readers have also had their accounts deleted. But in this cat and mouse game, my audience and I try to find each other again and make contact again. My black and red drawings have become a very easy symbol to identify.

But I have to acknowledge that with the clampdown on Sina Weibo getting more serious, my audience gradually moves from weibo users “inside the wall” to Twitter users who are free of censorship.

Besides Internet users, most of my friends in China don’t know about my drawings. Because I am afraid to reveal my identity, I’ve never revealed my drawing experience and artworks to friends in China. On one hand, this comes from my own need for safety, and on the other hand, I don’t want them to get involved with any unnecessary conflict. Occasionally when I raise the issues, some people hold an attitude of not understanding. Some people think I am stupid or don’t understand why if I left China I am still concerned with China’s problems. More often, people remind me to be careful.

CDT: What do you hope to accomplish with your drawings?

BDC: The starting point for drawing cartoons was my search for a way to vocalize and freely express my views on all sorts of issues. From another perspective, it was a way for me to uncover my own courage.

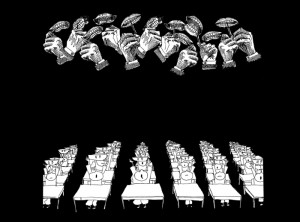

I hope my work will become a record of my personal perspective on social issues and history. In China, history is constantly being unified and tampered with, and even forgotten. On the other hand, individual tragedy is engulfed by the grander narrative.

As a rebel, I want to use my pen to record history from my perspective, and use my individual perspective to confront the official record. Of course, as one person I can’t do enough, so I hope more people will contribute to this record, because the more diverse perspectives we have, the more objective the record will be that is left.

I also hope to use the comic exaggeration and humor of cartoons to deconstruct the arrogance and authority of China’s dictatorship, because the collapse of authority is the building block of individual awakening and free independence.

CDT: Are you politically active in other areas besides your art?

BDC: Except for artistic expression, I don’t do much in other areas. Living in a foreign country, I can’t physically be present at the scene. For many things, I can appeal and show solidarity verbally. I also participate in Sina Weibo and Twitter and other social media to express my opinions in writing, and I donate to the families of political prisoners, sign petitions to stop the self-immolations in Tibet, and other activities.

CDT: What other contemporary Chinese cartoonists do you admire?

BDC: The cartoonists I admire are Hexie Farm, Biantai Lajiao (Rebel Pepper), and Kuang Biao. Although they live in China, these three speak out and refuse to self-censor, which is very rare and commendable [Editor’s note: Hexie Farm actually lives abroad currently. He also has been a CDT contributing cartoonist.]

I appreciate the unique charms of Hexie Farm’s fearless material and fairytale images, Biantai Lajiao’s simple style and sharp attitude, and Kuang Biao’s delicate brushstrokes and profound meaning.

CDT: What is the significance and meaning of the name you chose, Badiucao (巴丢草)?

BDC: There are really not many things to say. I know many artists pick their name carefully to make sure it contains great meaning. Mine is more like you randomly open a dictionary and pick whatever word appears at top. I know it is probably not beneficial for people to remember my name, but it is true. : )

CDT: Anything else you want to tell the CDT audience about yourself or your work?

BDC: Being a political cartoonist in China is both unfortunate and fortunate. The unfortunate part is, every day tragedies and theater of the absurd scenes are staged in China. I have to force myself to watch them, to feel, to think and to create. Although my work may be humorous or ironic, the process is full of pain and frustration.

The fortunate part is that, possibly no other country’s cartoonists have such a wealth of resources for their creative process.

I hope that one day, there is no need for such misfortune, and no need for too much fortune. I hope that one day, a normal, dull life can be staged in China. But until those dull days come, I will keep on drawing.