Xinhua reports that new reforms of China’s petitioning system announced on Tuesday promise to control official abuses associated with the long-established appeals system.

According to a set of guidelines released by the general offices of the Communist Party of China Central Committee and the State Council, authorities will stick to lawful means to dissolve conflicts and disputes.

Any malpractice that constrains the public from legal petitioning will be rectified and prohibited.

[…] Many complaints are filed each year in China, in which petitioners generally see injustice in land acquisition, social security, education, healthcare or environmental protection.

They can supposedly take their grievances to a higher level if they fail to get satisfactory feedback from local petition offices, but local officials often prevent them from raising such cases with their superiors.

[…] The guidelines asked officials to accept petitions from the public in a face-to-face manner at intervals ranging from one day in six months for provincial-level officials and one day every week for township ones. [Source]

Reuters’ Megha Rajagopalan also reported on the reforms, noting that petitioners will be obliged to pursue their cases at the local level first, and describing in more detail how “local officials often prevent them from raising such cases with their superiors”:

[… P]etitioners must not “leapfrog” their complaints to higher authorities, say the guidelines released by the central committee of the Communist Party of China and the State Council, or cabinet.

Petitioners are frequently forced to go home or held in unlawful black jails, where they face beatings, starvation and sleep deprivation. [Source]

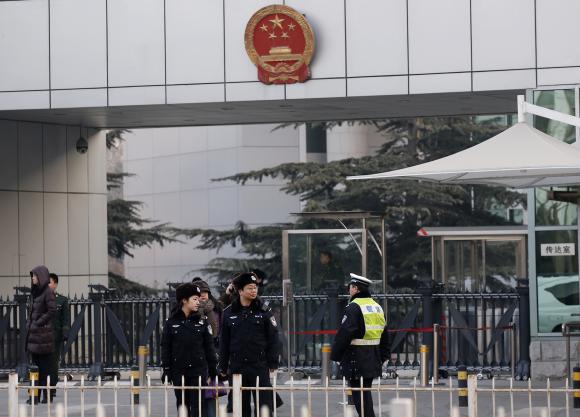

Because local governments are fearful of complaints against them reaching Beijing, many petitioners are forcibly intercepted and placed in official detention centers or unofficial black jails before being returned to their homes. Others are persuaded to go home voluntarily but arrested when they arrive. Even for those who stay, success is far from assured, and may take years to achieve. Frustration with the process drives some petitioners to appeal to foreign journalists: some traveled to Jinan last year to try to capture some of the media attention surrounding Bo Xilai’s trial. In more extreme cases, some have resorted to suicide attempts or bombing attacks. See a recent overview of the petitioning system by Tyler Roney at The Diplomat, via CDT.

There have been some efforts in the past to punish abuses: Beijing police reportedly investigated accusations of illegal detention in 2011, for example, and ten people from Henan were convicted a year ago for illegal imprisonment. But the central government’s motivations on the issue are mixed: Human Rights Watch’s Nicholas Bequelin explained last year that “Beijing’s message to the local officials has been: one, we don’t want your petitioners in Beijing, but two, we don’t want to know how you do that, and three, if something goes awry we won’t necessarily cover up for you.”