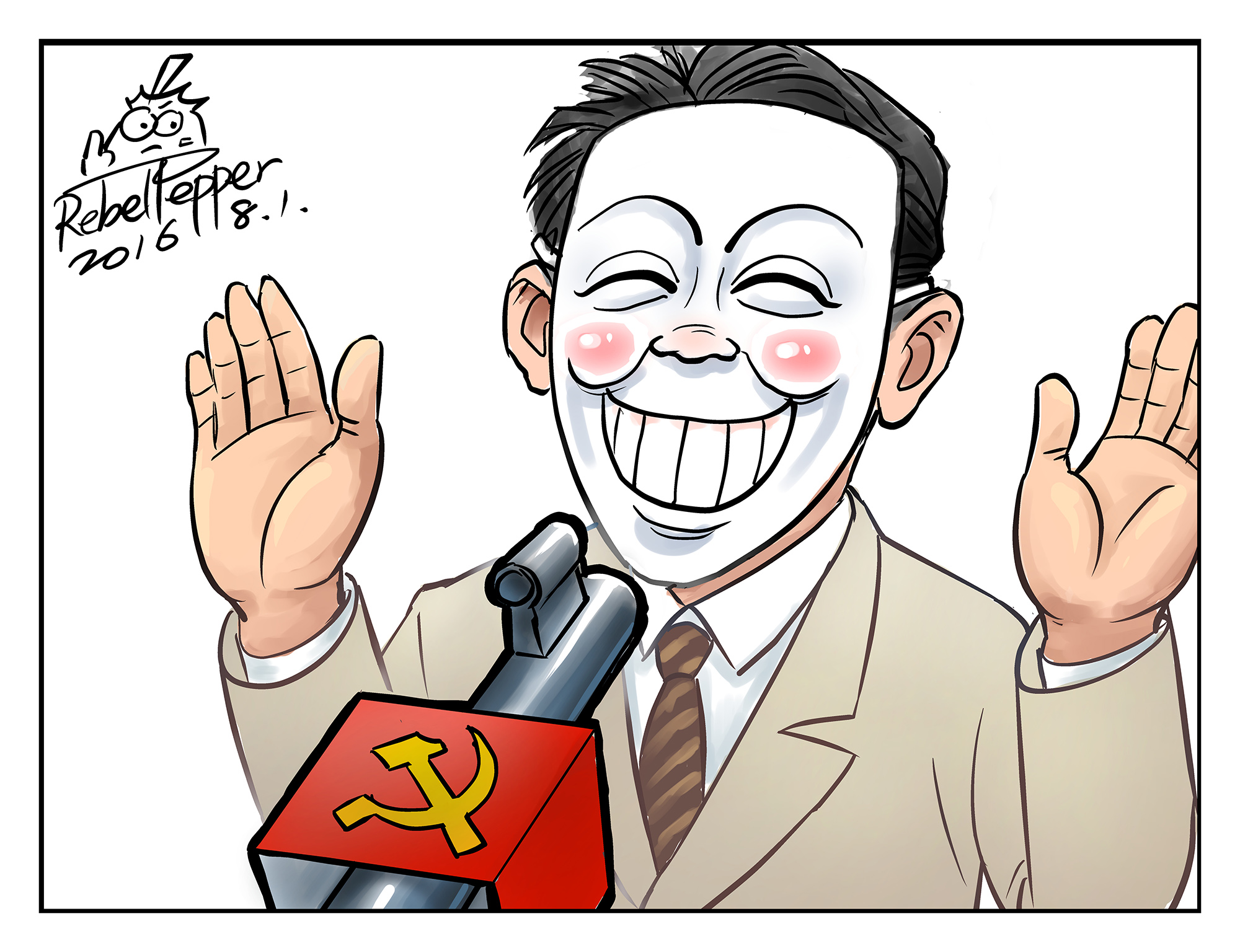

The ongoing crackdown on dissent in China, which has targeted rights lawyers and their associates, journalists and the media, activists, and others, has been called the harshest since the political campaigns waged by Mao Zedong. In the past two weeks, four rights lawyers have been sentenced on charges of subversion, and more trials are expected soon, for work that has previously been tolerated though not always welcomed. Recent detentions have featured the use of widely publicized and often televised confessions—presumably coerced—of defendants, a practice that was common during the Cultural Revolution era.

While the targeted groups have long been subject to government interference for their work, this round of arrests is different both for the public way they are carried out and the official effort to link them to “hostile foreign forces,” an accusation that has been felt in many areas of Chinese society in recent years including religious practice in Tibet. From Julie Makinen in The Los Angeles Times:

Just as the intensity of the crackdown may be underestimated by those outside of China, so too is the extent to which China’s propaganda apparatus has worked to paint those with even mundane grievances as the stooges of foreign enemies.

“The government has tried to deflect attention away from the clear violations of the defendants’ basic due process rights and right to a fair trial by painting them as part of a foreign plot,” said Frances Eve, a researcher with the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders, a group that has been advocating on behalf of detained lawyers and activists. “However, it’s absurd and insulting to insinuate that lawyers defending China’s most downtrodden and left-behind citizens are working on behalf of a foreign government.”

[…] China’s ominous warnings about “hostile foreign forces,” however, are not limited to dissidents and activists. They are part of a wider web of rhetoric that sees threats and meddling from abroad all around, while downplaying the possible domestic origins of conflicts and problems.

Communist Party leaders have, for example, pointed to the fact that some organizers of the 2014 Hong Kong democracy protests met with representatives of the National Endowment for Democracy, a Washington-based nonprofit group that receives an annual appropriation from Congress, as proof that the demonstrations were a U.S. plot. China recently warned citizens to be careful about dating foreigners, lest they turn out to be spies. [Source]

Jamil Anderlini of the Financial Times weighed in on the dangers of scapegoating foreigners and generating xenophobia in China, writing: “In liberal democracies with traditions of free speech, vociferous denunciations of these attitudes can act as a counterweight. But in authoritarian countries where alternative narratives are forbidden, official attempts to demonise foreigners and ‘others’ can be especially dangerous.”

For Global Voices, Oiwan Lam looks at the evidence used against the sentenced lawyers, and notes that almost any activity in China today could be considered “subversive” if so determined by authorities:

However, it still takes concrete evidence for building up a state subversion case. The critical evidence presented in all four cases concerns a dinner gathering at a Beijing restaurant called Seven-spice-BBQ (七味燒). The gathering was interpreted as a meeting that conspired to overthrow the ruling Chinese Communist Party. Following that logic, human right lawyers Liu Shuqin explained in the Weiquanwang, a website devoted to documenting Chinese human rights incidents, that anyone can be charged with subversion, if all its takes is the evidence that was presented on trial.

[…] Liu continues to explain that once the theory and the plan is established, all actions that challenge the government’s authority will be viewed as a subversive act, even though the action itself might be legal and well within Chinese law. More importantly, the lawyers and activists that pleaded guilty, were detained for more than one year without access to counsel and family, during which time their families were constantly harassed by the authorities. Liu concluded that the whole trial is a grand show for “foreign forces.” [Source]

As Maya Wang writes for NewsDeeply, the recent crackdown on lawyers has been especially harsh for the families and associates of those arrested, who have themselves been subject to detention and harassment for inquiring into the whereabouts of their detained loved ones:

Since the government detained two dozen human rights lawyers and activists in a July 2015 sweep, their spouses, children and other family members have suffered from not knowing where their relatives are, how they are being treated and when – and for what – they might be prosecuted. The authorities have also forced families out of their homes, denied them education opportunities, barred them from traveling abroad and put them under smothering surveillance. These totalitarian tactics seem designed to punish not only the detainees but also their families to deter others from taking up human rights work.

Yuan Shanshan, the wife of lawyer Xie Yanyi, was detained for three days, despite having committed no crime. All she did was to seek the authorities’ approval for Xie to attend the funeral of his mother, who had died while he was in detention. Although Yuan was pregnant, she was given very little food and water, denied toilet breaks and threatened and scolded by more than two dozen police officers in an interrogation room during her detentions.

After police took lawyer Wang Quanzhang away in July 2015, they confiscated Wang’s bank cards, leaving his wife Li Wenzu struggling financially. They then pressured Wang’s parents and sister to go on videotape to convince Wang to confess. Wang’s family remain under round-the-clock surveillance. [Source]

The threat of disenfranchised groups joining together with the help of lawyers, especially in a period of economic and social uncertainty in China, likely helped determine the government’s response, Yiyi Lu writes in The Wall Street Journal.

Why, now, are dissidents being charged with political crimes?

Many argue the shift in treatment of dissidents reflects a growing paranoia inside the Communist Party about social unrest and challenges to its rule from civil society and rights activism. A fear of different social groups linking up to launch coordinated action was clearly evident in the trials, where prosecutors accused the four men of trying to connect the separate circles of activist lawyers, petitioners, underground church members and pushers of viral online content.

But if fear is the driving force behind the trials, then why advertise them so widely?

A different way of understanding the prosecutions and the propaganda around them is to view them as part of a larger attempt to politicize the defense of individual rights in general. In China, the term weiquan, or “rights defense,” refers to both legal and extra-legal actions that individuals and groups take to defend their private or public rights and interests. As rights consciousness rises and mounting economic and social problems affect an increasing number of the population, the ranks of rights defenders have continued to grow. [Source]

Yet even within the restrictive environment for rights lawyers and others rights advocates, there have still been a few bright spots in the prospects for legal reform in China, as citizens are increasingly using the courts to defend their rights, according to an article in The Economist:

In the past year, the number of cases accepted by courts relating to the rights of socially marginalised groups has surged, even though few have won. They include a lesbian student suing the education ministry for textbooks calling homosexuality a disorder; the country’s first transgender employment discrimination case; and dozens of food-safety and environmental-protection suits that challenged large companies. In a landmark victory in April, a court in the south-western province of Guizhou ruled that a local education bureau must pay a school teacher compensation after he lost his job for testing HIV-positive. China has no specific laws against employment discrimination and the case was reportedly the first of its kind.

Stanley Lubman, an American legal scholar, says the ability to sue government agencies is important and the increased pursuit of such cases reflects a greater legal consciousness among citizens. Two other things are contributing to the changes. One is progressive legislation, such as recent new laws to protect the environment and punish domestic violence; these have widened the space for litigation. A pilot reform launched last year even encouraged state prosecutors to pursue public-interest suits.

The other is social media. Sun Wenlin, a 27-year-old IT worker who is half of the gay couple in Changsha, is optimistic in spite of losing his case. “Homosexuality is taboo and we thought no one would care. But our case generated a lot of discussion on the internet. We had sympathetic coverage even in state-owned media,” he says. Mr Sun now gives workshops around the country to teach others how to file similar lawsuits, hoping to change the belief among cynical Chinese that the law is just a tool of oppression. “China is clearly changing, but slowly,” he says. [Source]

In an Asia Society discussion, University of Pennsylvania’s Neysun Mahboubi and Fordham’s Carl Minzner had different takes on prospects for the development of rule of law and legal reform in China. Mahboubi believes that despite Xi’s efforts to centralize power, personnel at lower levels of the political and legal sectors may be more willing and able to promote positive change:

So, even if you could say that a lot of the language about law and legal institutions that comes from Xi Jinping and the top leadership may be more in the nature of trying to strengthen institutions in order to secure Communist Party rule, or to make authoritarian governance more effective or more efficient, even if that’s the case, the people who are populating the legal system—the judges, the professors, the officials within the National People’s Congress—those people have a different set of values and ideas about the significance of law and legal values. It has seemed to me that the space afforded by the positive language of the Fourth Plenum Decision, and the rhetoric about law and legal institutions associated with that, has given that group of people some additional scope to push things forward. Indeed, those are the kinds of people who participated in the drafting of the Decision, who put in all that technical language that I’ve been highlighting. And so that to me is ultimately the cause for hope, that people like that exist and have space to function within the system. As we all know, China is fragmented and there are a lot of different things going on, and these people don’t necessarily share the same values, or hold the same approach to law and legal institutions that the top leadership does, and they do have some space to push things forward. Now, whether or not that’s enough to overcome the more negative aspects of the story, I don’t know. But at least there’s some grounds for hope. [Source]

Minzner, on the other hand, has a more pessimistic take on the outcome of Xi’s consolidation of power and the future of the rule of law in China:

I think the entire reform era of the Chinese party-state’s effort to build more institutionalized systems of rule is being reversed. What is happening is that this failure to push political reform in an earlier period is now leading the entire system to cannibalize itself and its prior political institutionalization.

Note that this isn’t the same thing as saying that Xi is the new Mao. If you were an optimist, you would note that there are still important differences. For all of the centralization of power that’s going on, you still don’t see him calling the people out onto the streets to engage in Maoist style mass movements. Until you go to that step, you really can’t say that this is full-blown Maoist. Now, if you’re a pessimist, you might say that we haven’t seen that yet. You would note that you can’t get to mass movements until you’ve cultivated a cult of personality, established heavy control over the media, centralized power to a sufficient degree, etc. Moreover, it’s more likely that you might start to get things like that happening when you see the economy really hit a wall, for example, or when Xi starts to run into significant difficulties imposing his will on a recalcitrant bureaucracy. In such a situation, resorting to that last step of then going back to the streets in a Maoist style mass movement might not only be conceivable, but it actually might also be entirely rational behavior from Xi Jinping’s own perspective. [Source]

Read another forum on the rule of law in China with Joshua Rosenzweig, Ewan Smith and Susan Trevaskis via Chinoiserie.

For more on the trials of rights lawyers, see “Annotated Excerpts from Hu Shigen and Zhou Shifeng’s Trial Transcripts” from Human Rights in China.