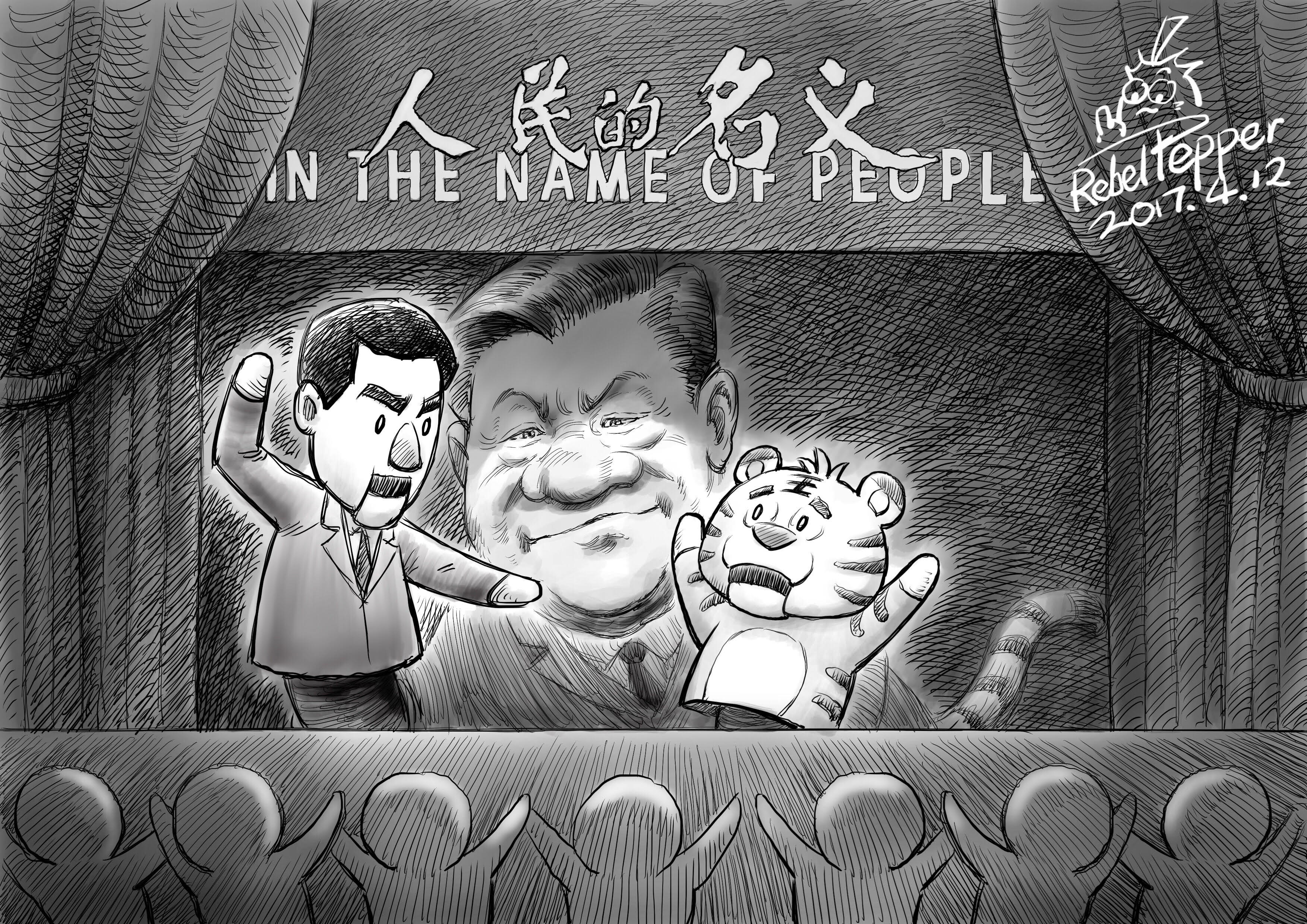

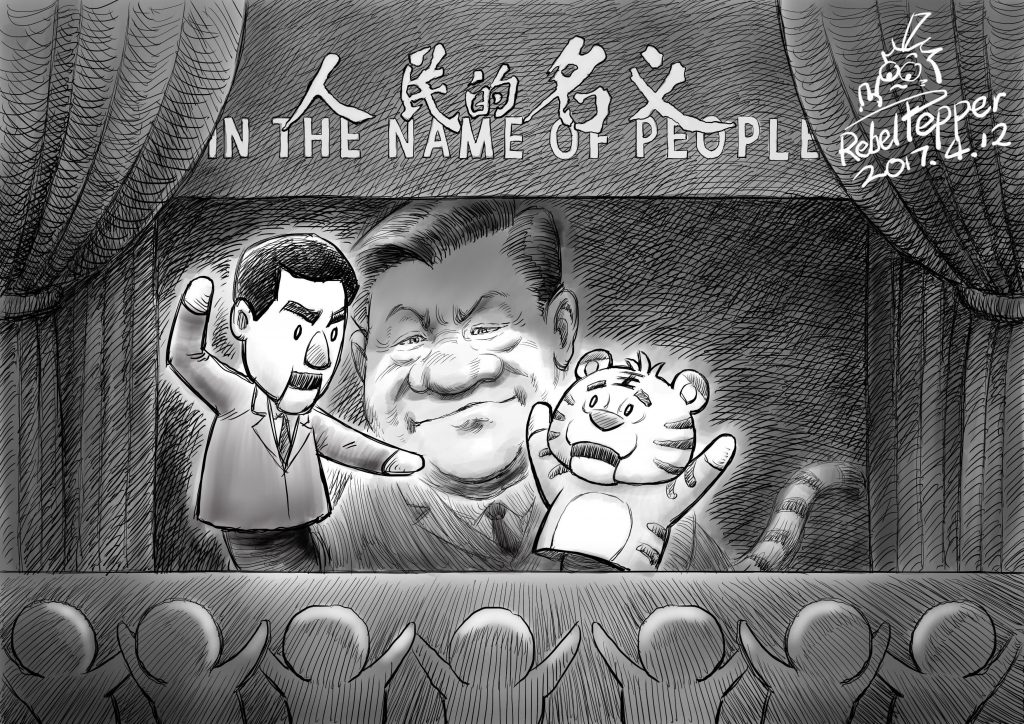

A new 56-episode series from Hunan Television, In the Name of the People, has become a popular favorite for its “ripped from the headlines” approach to covering dramatic stories of official corruption and deceit. But cartoonist Rebel Pepper sees the show as an effort by China’s leaders to manipulate the public, writing that, “If Xi Jinping hadn’t given his personal approval, how could this show receive such high-profile publicity? So this series is still only using the name of the people to fool the people.” In Rebel Pepper’s drawing, Xi Jinping pulls the strings on a puppet cracking down on a “tiger,” Xi’s terminology for a high-level corrupt official, while the audience cheers:

The BBC has more on the show and the public response:

In the show, local government leaders try to sabotage a top justice’s arrest order; laid-off workers hold violent protests against a corrupt deal between the government and a corporation; and fake police drive bulldozers into forced eviction sites.

Viewers have been lapping it up. “This TV drama feels so real. It really cheers people up,” one viewer wrote on social media network Weibo.

“I shed tears after watching this drama. This is the tumour of corruption that has been harming the people,” said another Weibo commenter.

What makes In The Name of the People remarkable is not just how frankly it depicts the ugly side of Chinese politics, but that it also has the blessing of the country’s powerful top prosecutors’ office. [Source]

Televised dramas depicting official wrongdoing and the inner workings of the government are generally censored in China. But the emergence of this show reflects a new confidence from the Xi administration, according to a report by Nector Gan of the South China Morning Post:

China’s media watchdog decided to curb the genre in 2004 because it exposed excessive details of corruption, even imaginary ones, which Chinese officials thought could undermine public confidence in the ruling party.

The production and broadcasting of In the Name of The People on prime-time screens, therefore, reflects Beijing’s growing confidence that it is able to control the anti-corruption narrative and convince the public that one-party rule can also be clean.

[…] The party’s disciplinary watchdog under Wang, the Central Commission for Discipline Inspection (CCDI), has already made two documentaries hailing the campaign.

While the documentaries were eye-popping – featuring toppled provincial officials tearfully confessing in public – the powerful CCDI is trying to grab the attention of the general public, especially young people who prefer to watch TV dramas online rather than dry political documentaries on state television. [Source]

The show has been popular with the TV audience, with more than 350 million views of the pilot. Yet feminists are viewing it with a critical eye due to its demeaning portrayal of women. From Lin Qiqing at Sixth Tone:

The protagonists in the drama are an all-male panel of high-ranking officials, whereas the show’s female characters are all flawed women who conform to traditional gender roles: a reckless employee, an obedient housewife, and a businesswoman who sleeps her way to success.

“The portrayals of female characters, especially the gender relations in the drama, are unrealistic and are full of stereotypes,” Shen Yifei, associate professor of sociology at Fudan University, wrote on her public account on messaging app WeChat on Sunday.

In her article, Shen cited an example from the show: The head of Handong’s anti-corruption department, Lu Yike, frequently comes off as incompetent and is constantly quarreling with her superiors. “It’s as if all of her value lies in helping to cook,” Shen wrote, referring to a scene in which Lu is asked by her boss to prepare a meal for a visiting official. Lu is also continuously urged to get married by her mother, her boss, and even her subordinates. [Source]