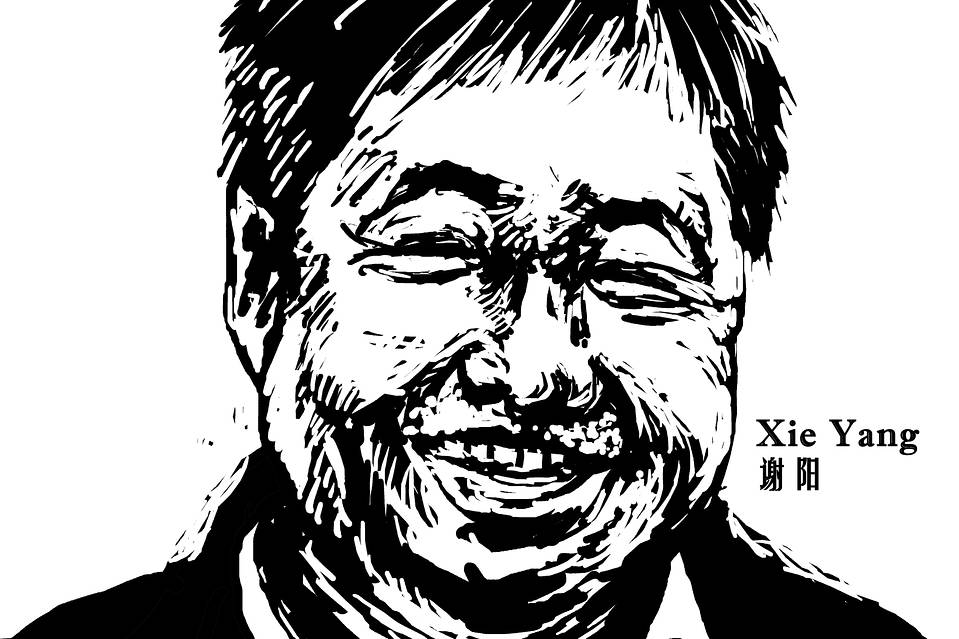

Rights lawyer Xie Yang stood trial in Changsha on Monday, nearly two years after his detention in the 2015 Black Friday or 709 crackdown. Xie’s claims that he was tortured during the investigation against him drew global attention, but authorities dismissed his accusations as “fake news,” and last week detained his former lawyer, who had helped leak them. (China has rejected U.N. protest at this latest development as “an interference in China domestic affairs and judicial sovereignty.”) Xie had been expected to stand trial two weeks ago, but the proceedings were indefinitely postponed without notice. Several 709 detainees have been tried since last August, most recently fellow rights lawyer Li Heping late last month.

From Christian Shepherd and Philip Wen at Reuters:

According to the transcripts, Xie, 45, confessed to charges of [inciting] subversion and disrupting court order and expressed repent. The court also released a short video that showed Xie saying he had not been mistreated while in custody.

Xie, who had worked on several cases deemed politically sensitive by China’s ruling Communist Party, also said he had undergone “training” on three occasions in Hong Kong and South Korea, where he was “brainwashed” into trying to promote western constitutionalism in China.

“My actions go against my role as a lawyer,” Xie said in the video, reading from a page. “I want to take this opportunity to express to other rights lawyers my view now that we should give up using contact with foreign media and independent media to hype sensitive news events, attack judicial institutions, and smear the image of nation’s party organs while handling cases.”

Among the evidence prosecutors produced against Xie were his actions in drawing attention to a civilian shot dead by police at a railway station in northeastern Heilongjiang province in May 2015. Other evidence included extensive logs of Xie’s Weibo posts, as well as his conversations on messaging app Telegram. [Source]

The focus on foreign instigation is part of a recently resurgent pattern in politically sensitive trials and elsewhere. The appearance of posts from Telegram may deepen existing concerns about the “supposedly secure messaging app.” Messages on China’s homegrown WeChat service also appear to have been used against political targets such as activists and journalists.

In January, Xie issued a note urging supporters to disregard any subsequent guilty plea. From China Change:

If, one day in the future, I do confess — whether in writing or on camera or on tape — that will not be the true expression of my own mind. It may be because I’ve been subjected to prolonged torture, or because I’ve been offered the chance to be released on bail to reunite with my family. Right now I am being put under enormous pressure, and my family is being put under enormous pressure, for me “confess” guilt and keep silent about the torture I was subject to.

I hereby state once again that I, Xie Yang, am entirely innocent. [Source]

Before the trial, Xie’s wife Chen Guiqiu answered challenges to his accounts of torture with a description—also translated by China Change—of the channels through which she had heard of it, including “individuals in the security police and the public security system whose conscience has not been lost.” Chen was dismissive of her husband’s courtroom confession, as South China Morning Post’s Nectar Gan reported alongside other reactions:

Xie’s wife, Chen Guiqiu, said she believed her husband had been forced into discrediting himself. “This is all a show put on by [the authorities]. I believe Xie only complied to save his own life because he had been subjected to inhuman, unbearable torture in the past months,” said Chen Guiqiu, who now lives in the United States. She fled to the US via Thailand with her two daughters with the help of US embassy officials, the Associated Press reported on Monday. [See report.]

[…] Albert Ho Chun-yan, chairman of [the China Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group, which organized the sessions Xie attended in South Korea], said the group often invited mainland rights lawyers to Hong Kong for exchanges that, for example, offered a look at Hong Kong’s judicial system.

[…] “According to the transcript, Xie said the event was also organised by the Hong Kong government. You don’t need me to tell you that [these claims] are problematic,” Ho said.

“[Xie] was tortured into conceding … Nobody would believe he willingly said what he said, and nobody would believe this was a fair trial.” [Source]

See more from The Guardian’s Tom Phillips, to whom U.S.-based rights lawyer Teng Biao commented that “it is very clear that these proceedings are totally arbitrary and illegal.”

Xinhua reported that “over 40 people, including Xie’s relatives and two defenders, legislators, political advisors, journalists from domestic and overseas media outlets and members of the public, attended the hearing.” As with the abrupt postponement of his trial two weeks ago, however, no notice of the event was given. The sudden changes may have been part of efforts to keep supporters and observers away. From the AFP:

There was no prior public notice of the trial, and Xie’s wife — who relocated to the United States earlier this year — told AFP she heard nothing from authorities.

“The court claims family members are in attendance at the trial, but I wasn’t able to reach any of them,” she said.

Last-minute delays or sudden announcements of sensitive trials are not uncommon even though Chinese law requires courts to give a defendant’s family and lawyers three days notice of any changes.

[…] Since they received no confirmation of the new trial date, diplomatic sources told AFP they were not prepared to head to Changsha again to observe the trial.

Local activists said in social media posts that they were “warned” on Sunday not to go to Changsha, without providing details about the warnings. [Source]

Last week, the U.S.-funded Radio Free Asia reported intimidation of supporters who had traveled to Changsha for the earlier trial, including one who claimed to have lost his job as a result. Activist Ou Biaofeng, noting the thin security presence at the courthouse last week, told RFA that “maybe the whole thing was a decoy, so that they would get an idea of who would show up, and they could get their details.”