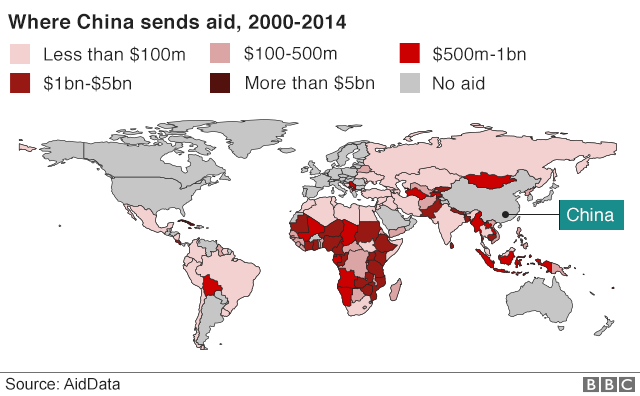

While China’s increasing foreign investments in nations in Latin America, Africa, and the Middle East have been well documented over the past 15 years, Beijing’s foreign assistance spending is officially classified as a state secret. A report and dataset published today by the AidData Research Lab at the College of William and Mary has revealed that the amount of assistance funds flowing out of China from 2000-2014 was nearly equal to that of the U.S., the world’s biggest donor ($362 billion, compared to the U.S.’ $399 billion). The study also shows that China’s motivations for spending represent a radical departure from global assistance norms that could have major consequences. At BBC News, Celia Hatton reports on how the AidData researchers conducted their study despite state sanctioned opacity on the topic, and on the profit-driven motivations for Beijing’s assistance that the data suggests:

[…] The AidData team had to develop its own methodology to answer the questions that weren’t provided by the Chinese government. They tracked money flows from China to recipient countries using news reports, official embassy documents and aid and debt information from China’s counterparts.

[…] “We think the methodology has revealed the known knowable universe,” Brad Parks says. “If the Chinese government really wants to conceal something, we won’t necessarily pick it up.” But if there are sizeable money transfers going from China to a recipient country, “word is going to get out”, he adds.

[…] The vast majority (93%) of US financial aid fits under the traditional definition of aid that’s agreed upon by all Western industrialised countries. That aid is given with the main goal of developing the economic development and welfare of recipient countries. At least a quarter of that money represents a direct grant, not a loan that needs to be repaid.

In contrast, only a small portion (21%) of the money that China gives to other countries can be considered as traditional aid. And the rest of that money? The “lion’s share” of that money is given in commercial loans that have to be repaid to Beijing with interest.

“China wants to get attractive economic returns on its capital,” Brad Parks explains. […] [Source]

The “traditional definition of aid” that makes up 21% of Chinese outflows described above refers to “official development assistance” (ODA) as defined by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD)’s Development Assistance Committee. China isn’t a member of the OECD, which allows it to mix commercial financing into aid packages in a way that has raised alarm. The Wall Street Journal’s Eva Dou reports:

The U.S. and other member countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, a Paris-based research body, agreed in 1978 to restrict the practice of requiring aid recipients to purchase goods and services, and to limit how aid can be mixed with commercial financing, said Brad Parks, AidData’s executive director. China isn’t a member of the OECD, so isn’t bound by the agreement.

“This practice has raised serious alarm among countries that do not blend their development finance and trade finance,” said Mr. Parks.

The U.S. Export-Import Bank warned in its annual competitiveness report this summer that the agreement may suffer from China’s use of “mixed credits,” which combine regular export credits with aid or aid-like loans.

The result is financing packages that countries adhering to the OECD agreement can’t match, the report said. [Source]

The data shows that commercial interests aren’t the only ones driving Beijing’s allocation strategy. At The Washington Post, Adam Taylor cites experts on the political self-interest apparent in Beijing’s strategy for allocating ODA, and cites AidData’s Park on how the the “lion’s share” of Chinese aid does appear to be profit-oriented:

The data set suggests Chinese aid is instead generally motivated by two interests: the need level of the recipient country and the broader foreign policy aims of China. AidData found African countries that vote with China at the United Nations get an average bump of 86 percent in aid from Beijing.

“The criteria for China to provide foreign aid is not the nature of the government, but the convergence of interests,” said Yun Sun, an expert on Chinese funding who is with the Stimson Center in Washington. “That need could be political, commercial, or even reputational.”

[…] AidData’s research also shows the lions share’s of China’s global development spending is not official aid but rather distributed via “other official flows,” or OOF. This bracket of funding includes huge deals, like the enormous loans given to Russian oil companies in 2009, in which the motivation is clearly commercial.

“ODA and OOF really need to be considered separately,” Park said. “If the country is rich in natural resources, if it trades a lot with China and if it is credit worthy, it tends to get a lot of OOF.” China’s widespread funding of more commercially minded projects is what sets it apart from Western donors, who have largely moved away from loans toward grants. “China is operating to its own rules,” Park said. [Source]

On Twitter, Winslow Robertson, a specialist in Sino-African relations, disagreed with the categorization of “other official outflows” as aid:

Unsure why these flows are categorized as aid or development spending when they are clearly not. pic.twitter.com/Y6RBMPKlsh

— Winslow Robertson (@Winslow_R) October 11, 2017

At CBC, Nahlah Ayed and William Wolfe-Wylie cite an expert on why Beijing considers this foreign aid data a state secret:

[…] China’s secrecy on foreign aid is partly because of “domestic politics,” says Mathieu Duchatel, senior policy fellow and deputy director of the Asia and China program at the European Council on Foreign Relations.

“The argument is that people in China would not be very enthusiastic to hear that China is spending lots to promote development overseas when China has domestically still a lot of people to take out of poverty,” he said.

[…] It may also be, partly, sensitivity about China’s image abroad.

“China feels that it’s under a lot of scrutiny from many observers around the world and a lot of people are discussing the rise of China as a major global actor, with geopolitical ambitions.” [Source]

On the domestic political front, Chinese netizens coining of the nickname “Big Spender” (Dà Sābì 大撒币, a word with an luridly insulting near homophone) indeed suggests a general public disapproval for spending massive amounts of state money abroad.

The release of the AidData study comes as the U.S.—still the world’s largest foreign donor, according to the study’s estimates—is led by an administration that has pledged to put “America First,” and significantly cut foreign aid outflows. At the South China Morning Post, Kingling Lo notes that this could set China up to soon become the world’s biggest aid donor—if only rhetorically so:

China has further opportunities to project soft power through aid spending following US President Donald Trump’s announcement in March that he wanted a 32 per cent cut – equivalent to about US$13.5 billion – in all non-military spending abroad.

[…] Parks said he did not think it likely that China would surpass the US in terms of ODA funding, but said it was highly likely to become the largest aid donor using the broader definition.

“We can see over time there is a steady increase in China’s overall spending in the provision of ODA and OOF. I don’t think there are any signs of slowing down,” he said. [Source]