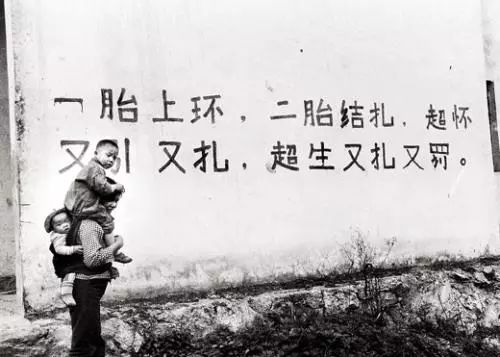

In 2015, the Chinese government officially reformed its infamous one-child policy to a “two-child policy,” relaxing the family planning rule that critics had long cautioned was contributing to demographic distress. Following the move, experts warned that it would not be enough to answer the challenges facing Chinese society after four decades of a one-child policy. Beyond that, other unexpected challenges have arisen from the two-child policy, and the demographic trend-correcting baby-boom that the change was intended to catalyze has so far not materialized.

As some Chinese regions attempt to offer other incentives to stimulate a faltering birthrate and official moves are read by some as hints that further relaxation of the policy is imminent, an essay on WeChat tells the birth story of a so-called “black child” (hēi háizi 黑孩子)—born illegally at the height of China’s family planning restrictions. CDT has translated the full essay, written by @HuoLaoye (霍老爷):

My mother gave me three lives.

In my family I was the third eldest, born in the 1980s. Children like me are known as “black children,” not because our skin is black, of course, but because we exceeded the birth-control policy and have no hukou.

I was born at a time when China’s family planning policy was at its strictest. My parents didn’t originally plan on having me. My father recommended I be aborted, but my mother cried for a long time—the child is soon coming to us and for him to never get the chance to see us is such a pity.

So the two of them decided that I’d be born.

My mother’s stature was slender, she worked just like everyone else. At first others didn’t know about me, but later I was discovered and reported. At that time, family planning held veto power over all else. If a single county was caught breaking the policy, then all other good work it had done would be for naught. The county CCP secretary had to personally lay down military order.

At about the six-month mark, a group of people rushed into our home, some wearing white gowns and others cadres with stately four-pocketed uniforms, wanting to take my mother to a county health institution. At the time my mother was kneading dough, and her hands were covered with flour. Seeing so many people, she knew she couldn’t run. She just said: “Can I bring a quilt?”

One cadre shot her a glance and said: “What need is there for a quilt? We’ll get you to the hospital and under the knife, then you’ll come right back home.” Mother says she still remembers that cadre’s face.

Mother could only easily grab my older sister’s small cotton-padded jacket.

When mother was taken to the health institution, there were already many pregnant women there. She guesses there were close to a hundred.

Only later did she know, the county wanted to “kill the chickens to warn the monkeys.” They launched a “hundred-day battle” to suppress those who had exceeded the birth control policy.

That was in the autumn, and mother was wearing an unlined garment. The evenings were already very cold, and she had only that small cotton-padded jacket to defend against the cold.

The next afternoon she saw two big trucks arrive at the health institution, and realized that they could be taking people to the city hospital to induce labor. She pretended to wet the small jacket, then told the hospital staff her man was elsewhere, and asked if a fellow villager could take a letter back asking my father to send her a quilt. That cadre said, “Send what quilt? Soon you won’t be able to use it.” My mother immediately understood what he meant.

That evening, she pretended to go check if the jacket was dry, and stealthily snuck out the back door hoping to escape, not knowing that there was an old man watching the door.

She slowly tried to make friends with him, asking him where he was from, who was in his family.

She dilly-dallied there and didn’t go.

The old man directly said: “Don’t waste your time and energy. I am here [to guard the door], I can’t let you go.”

My mother said: ”I don’t want to go, I just want to chat with you. Do you have any children?”

The old man said: “There are two sons in my family, neither of them do what they are told.”

My mother said: “Your accent sounds like you’re from near to my village. I want to give birth to this one, I reckon it is also a son. Another one who won’t do what he is told.”

That old man suddenly said, “If you want to go, then go. But don’t go through the back door, there’s a wall. If you can climb then go ahead and climb. If you make it over, count it as your son’s good luck.”

I don’t know how she made it over, but to summarize, my mother carried her 6-month pregnancy up a 2-meter wall, jumped down the other side, and that night rushed a dozen miles to arrive at the home of my father’s uncle.

The pregnant women who were in the health institution were taken the next day to the hospital for induced labor. Of nearly a hundred children, not one of them was born alive.

My mother stayed for three months in another person’s home fearing that her relative was dissatisfied with her, dragging herself around to cook their food and wash their clothes. But her months were stacking up and the relative also didn’t dare keep me—when he came or went there would always be neighbors pointing fingers. Some said those who permitted a birth-exceeding pregnant lady to stay in their house would bring ruin down upon their household.

Mother also didn’t dare to stay anymore. She sent word for my father to come and get her. But by afternoon, he still wasn’t there yet when she started to feel unwell—she thought she’d be giving birth soon. She insisted on leaving. My father’s uncle’s family was already afraid of getting into trouble, so they quickly let my mother go.

She couldn’t head into the city to find my father, she could only go to her hometown. But she didn’t dare to do so in daylight or on the main road for fear of being arrested. She camouflaged herself for the dozen mile journey. Who knew it would start raining at the halfway point, and it was almost four in the morning when she arrived home.

Just as she arrived, the wife of a neighbor helped her to give birth, and I was born without a hitch, seven jin and four liang [about 8.16 lb]. Mother said, “This child really is heavy, he knew it wouldn’t be easy for him to be born, so he seized his chance and made his way into the world.”

My mother wasn’t very cultured, but on that day there was no one else around. She thought a while and said: “This child was born at 4:00, at a time of clearing weather, his name should have the characters for ‘dawn,’ and ‘clear sky,’ and so the moment the sky alit, all was well. ”

Perhaps it was as she wished, since I was little I’ve met no illness or calamity. Even though I was a black child, I grew up in good health.

But since then, she has had some ailments—varicose veins, which are said to be from walking too far on foot.

Some people think that family planning is right, while others think it is wrong. I don’t know, but I do know one thing: my mother rebelled against family planning policies to give birth to me. This is an epic of our family, and one day I’ll tell my son and grandson about it. [Chinese]

Translation by Josh Rudolph and Lisbeth