On Tuesday, the Washington Post’s editorial board responded to the latest flurry of developments involving Google’s controversial secret development of a search engine designed to accommodate Chinese censorship and surveillance demands. The editorial follows fresh calls from Amnesty International for Google to abandon the project, followed by a pair of employee petitions both for and against it, each signed by hundreds of company staff, as well as preparations for possible strike action.

Google says it followed proper procedure during planning for the product, which the company continues to characterize as merely “exploratory.” Executives should stop exploring and recognize reality: By bringing its search back to China, Google would become a part of a censorship and surveillance apparatus that cuts against everything the company claims to stand for.

[…] Google’s goal has always been to build a more open world through a more open Web. China’s goal has been just the opposite: cyber-sovereignty, or a siloed system of national Internets where each country dictates what makes it in and what makes it out. Google would give its imprimatur to this destructive vision. It would tell other countries that they, too, can have Google’s services on their own terms, without committing to the free flow of information. Over time, that flow would thin.

If Project Dragonfly’s future is as uncertain as Google claims, the company still has time to change its mind. By protesting a closed-off effort to bolster a closed-off system, employees are proving they remain committed to their company’s animating principles. Executives should show they are committed, too. [Source]

The Post’s editorial echoes Amnesty’s message last week, which was accompanied by protests outside Google offices around the world.

“This is a watershed moment for Google. As the world’s number one search engine, it should be fighting for an internet where information is freely accessible to everyone, not backing the Chinese government’s dystopian alternative,” said Joe Westby, Amnesty International’s Researcher on Technology and Human Rights.

[…] “Google needs to stop equivocating and make a decision. Will it defend a free and open internet for people globally? Or will it help create a world where some people in some countries are shut out from the benefits of the internet and routinely have their rights undermined online?” said Joe Westby.

“If Google is happy to capitulate to the Chinese government’s draconian rules on censorship, what’s to stop it cooperating with other repressive governments who control the flow of information and keep tabs on their citizens? As a market leader, Google knows its actions will set a precedent for other tech companies. Sundar Pichai must do the right thing and drop Project Dragonfly for good.” [Source]

The open letter against Project Dragonfly last week, part of a reportedly vibrant but usually hidden corporate tradition, was the first open expression of opposition to the project from named current employees. From 11 initial signatures last Tuesday, the roster has now grown to over 700. The letter argued:

We are among thousands of employees who have raised our voices for months. International human rights organizations and investigative reporters have also sounded the alarm, emphasizing serious human rights concerns and repeatedly calling on Google to cancel the project. So far, our leadership’s response has been unsatisfactory.

Our opposition to Dragonfly is not about China: we object to technologies that aid the powerful in oppressing the vulnerable, wherever they may be. The Chinese government certainly isn’t alone in its readiness to stifle freedom of expression, and to use surveillance to repress dissent. Dragonfly in China would establish a dangerous precedent at a volatile political moment, one that would make it harder for Google to deny other countries similar concessions.

Our company’s decision comes as the Chinese government is openly expanding its surveillance powers and tools of population control. Many of these rely on advanced technologies, and combine online activity, personal records, and mass monitoring to track and profile citizens. Reports are already showing who bears the cost, including Uyghurs, women’s rights advocates, and students. Providing the Chinese government with ready access to user data, as required by Chinese law, would make Google complicit in oppression and human rights abuses.

[…] Many of us accepted employment at Google with the company’s values in mind, including its previous position on Chinese censorship and surveillance, and an understanding that Google was a company willing to place its values above its profits. After a year of disappointments including Project Maven, Dragonfly, and Google’s support for abusers, we no longer believe this is the case. This is why we’re taking a stand. [Source]

In addition to well-publicized protests, Dragonfly also has its defenders within the company. TechCrunch’s Jon Russel and Taylor Hatmaker reported last week on another letter that has circulated internally expressing qualified support for the project and attracting some 500 signatures. From the letter:

Dragonfly is well aligned with Google’s mission. China has the largest number of Internet users of all countries in the world, and yet, most of Google’s services are unavailable in China. This situation heavily contradicts our mission, “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful”. While there are some prior success, Google should keep the effort in finding out how to bring more of our products and services, including Search, to the Chinese users.

Dragonfly still faces many difficulties and uncertainties, which can only be resolved by continuing efforts. The regulation requirements set by the Chinese government (like censorship) makes Dragonfly a challenging project. If we are not careful enough, the project can end up doing more harm than good. In any case, only with continuing efforts on Dragonfly can we learn how different approaches may work out in China, and find out if there is a way that is good for both the Chinese users and Google. Even if we fail, the findings can still be useful for bringing other services to China.

Given the good motivation and the challenging nature of the project, we believe that Google should continue on Dragonfly, which benefits both Google and the massive user base in China. [Source]

Amid this unusually public exchange of views last week, The Intercept’s Ryan Gallagher, who first broke the story, reported on the lengths to which executives responsible for the project had gone to avoid or curtail internal debate, to the extent of shutting out Google’s security and privacy teams and even its famously rights-sensitive cofounder Sergey Brin.

Yonatan Zunger, then a 14-year veteran of Google and one of the leading engineers at the company, was among a small group who had been asked to work on Dragonfly. He was present at some of the early meetings and said he pointed out to executives managing the project that Chinese people could be at risk of interrogation or detention if they were found to have used Google to seek out information banned by the government.

Scott Beaumont, Google’s head of operations in China and one of the key architects of Dragonfly, did not view Zunger’s concerns as significant enough to merit a change of course, according to four people who worked on the project. Beaumont and other executives then shut out members of the company’s security and privacy team from key meetings about the search engine, the four people said, and tried to sideline a privacy review of the plan that sought to address potential human rights abuses.

[…] Google’s leadership considered Dragonfly so sensitive that they would often communicate only verbally about it and would not take written notes during high-level meetings to reduce the paper trail, two sources said. Only a few hundred of Google’s 88,000 workforce were briefed about the censorship plan. Some engineers and other staff who were informed about the project were told that they risked losing their jobs if they dared to discuss it with colleagues who were themselves not working on Dragonfly.

[…] Zunger does not know what happened to the privacy report after he left Google. He said Google still has time to address the problems he and his colleagues identified, and he hopes that the company will “end up with a Project Dragonfly that does something genuinely positive and valuable for the ordinary people of China.” [Source]

Citizen Lab researcher Lotus Ruan speculated about the possibility of what Zunger called “a Project Dragonfly that does something genuinely positive and valuable for the ordinary people of China” on Twitter on Tuesday:

been trying to write something about google's dragonfly project for a while. having talked to avg users and some scholars in china, my take on this issue has changed quite a bit.

— lotus (@lotus_ruan) December 4, 2018

to put it out there first, i am 100% against google keeping this project a secret and the lack of transparency and accountability is just astonishing.

— Lotus Ruan (@lotus_ruan) December 4, 2018

however, i m not so sure about the idea of advocating against a google search entering china, especially when a lot of advocates are coming outside china who are not immediately affected by the current (shitty) chinese search services.

— Lotus Ruan (@lotus_ruan) December 4, 2018

a simple search of medical services on baidu may lead to your death. using built-in services on uc/qq browser may subject users to vulnerabilities. meanwhile, a search of scholarly work on these browsers are largely incomplete

— Lotus Ruan (@lotus_ruan) December 4, 2018

so i m starting to think if introducing more competitions back into china may actually help china-based users and create a sense of crisis for local chinese companies. again, this is not to say that google's dragonfly project is okay. i m asking to re

— Lotus Ruan (@lotus_ruan) December 4, 2018

..to rethink the narratives on and strategies of keeping global companies in check when they deal with countries with bad human rights records.

— Lotus Ruan (@lotus_ruan) December 4, 2018

is it fair to advocate for a complete ban or are there other ways to hold them responsible while still allow users in those countries to enjoy the services

— Lotus Ruan (@lotus_ruan) December 4, 2018

Pichai stressed that he is “committed to serving users in China” in an interview with The New York Times early last month, but ended on an ambivalent note.

When I first joined Google I was struck by the fact that it was a very idealistic, optimistic place. I still see that idealism and optimism a lot in many things we do today. But the world is different. Maybe there’s more realism of how hard some things are. We’ve had more failures, too. But there’s always been a strong streak of idealism in the company, and you still see it today.

[…] There are areas where society clearly agrees what is O.K. and not O.K., and then there are areas where it is hard as a society to draw the line. What is the difference between freedom of speech on something where you feel you’re being discriminated against by another group, versus hate speech? The U.S. and Europe draw the line differently on this question in a very fundamental way. We’ve had to defend videos which we allow in the U.S. but in Europe people view as disseminating hate speech.

[…] One of the things that’s not well understood, I think, is that we operate in many countries where there is censorship. When we follow “right to be forgotten” laws, we are censoring search results because we’re complying with the law. I’m committed to serving users in China. Whatever form it takes, I actually don’t know the answer. It’s not even clear to me that search in China is the product we need to do today. [Chinese]

Lots to be said about Google/China, but this is not a CEO accurately assessing their trade-offs. https://t.co/suQf11auue

— Graham Webster (@gwbstr) November 8, 2018

John Hennessy, chairman of Google’s parent company Alphabet, made some similar comments in an interview with Bloomberg last month:

“The question that I think comes to my mind then, that I struggle with, is are we better off giving Chinese citizens a decent search engine, a capable search engine even if it is restricted and censored in some cases, than a search engine that’s not very good? And does that improve the quality of their lives?” Hennessy told Bloomberg’s Brad Stone.

Asked whether Google can do more good by being in China, even on a compromised basis, Hennessy said, “I don’t know the answer to that. I think it’s — I think it’s a legitimate question.”

“Anybody who does business in China compromises some of their core values,” he added. “Every single company, because the laws in China are quite a bit different than they are in our own country.” [Source]

Hennessy’s comments might seem encouraging to internal opponents of the project. But former Google engineer Jack Poulson, who left the company in protest at Project Dragonfly, responded skeptically at The Intercept, writing that “I object to this constant drift of conversations about Dragonfly from concrete, indefensible details toward the vague language of difficult compromise.”

IRONICALLY, I HAD no intention of speaking with the press until I later read an interview Hennessy had done as part of a promotion for his recent book, “Leading Matters.” When asked about Google re-entering the Chinese market, he dismissively said, “There’s a shifting set of grounds of how you think about that problem, and how you think about the issue of censorship. The truth is, there are forms of censorship virtually everywhere around the world.”

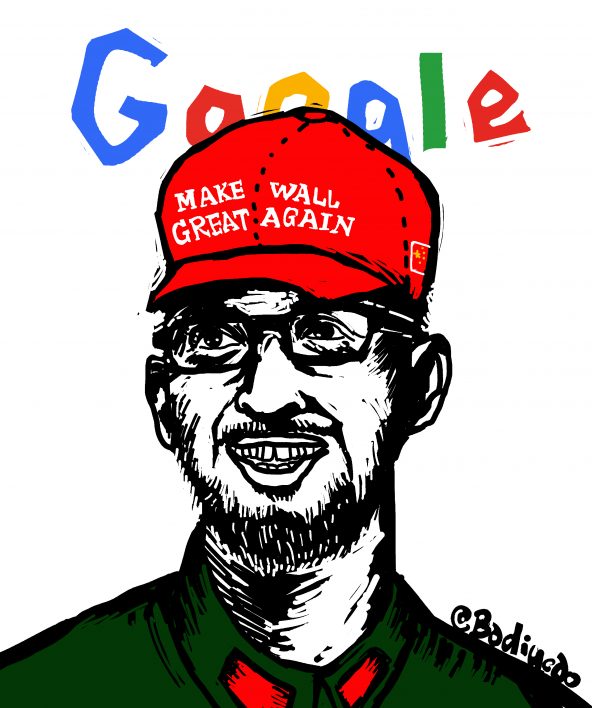

[…] Google CEO Sundar Pichai attempted to invoke an engineering defense by arguing that Google would not need to censor “well over 99 percent” of queries. Such a framing is perhaps the most extreme example of a broad pattern of redirecting conversations away from their concrete governmental concessions — which, again, literally involved blacklisting the phrase “human rights,” risking health by censoring air quality data, and allowing for easy surveillance by tying queries to phone numbers. Human rights and basic political speech are not an ignorable edge case.

[…] I, for my part, would ask that Sundar Pichai honestly engage on what the chair of Google’s parent company has agreed is a compromise of some of Google’s “core values.” Google’s AI principles have committed the company to not “design or deploy … technologies whose purpose contravenes widely accepted principles of … human rights.” [Source]