Beijing and Washington have been engaged in a steadily escalating back-and-forth campaign of COVID-19 blaming, with rhetoric becoming increasingly hostile on either side. While initially focused on guiding domestic public opinion through with positive, heart-warming stories from the frontlines, Chinese propaganda authorities in March turned their efforts outward, attempting to portray Beijing as an experienced leader and provider of aid in the global fight against the coronavirus pandemic. Just as these efforts have met with pushback and skepticism, the continuing propaganda push at home is also proving a hard sell to many.

At China Media Project, David Bandurski reported on Beijing’s “manipulation of human emotion as propaganda kitsch,” a tactic commonly used amid public calamity in China. Bandurski begins by highlighting writer Yi Zhongtian’s comment from February that “likened the excessive emotion, positivity and adulation in reporting and commentary on the coronavirus epidemic in China to ‘eating blood-soaked dumplings’ (吃人血馒头).” This is a reference to Lu Xun’s 1919 story “Medicine,” an allegory attacking superstition about an attempt to cure disease with dumplings soaked in the blood of an executed revolutionary. Bandurski continues to roundup examples of coronavirus propaganda kitsch that prompted pushback from the public and media:

One of several instances of “kissing up” that prompted Yi Zhongtian’s remarks on eating “eating blood-soaked dumplings” in February was a saccharine poem called “Thank You, COVID-19” that appeared on WeChat, and for many Chinese was too much to stomach. A taste of its nauseating sweetness:

I want to thank you, COVID-19, because you allowed me to see a blessing – unbreakable unity of will.

I want to thank you, COVID-19, because you allowed me to see a blessing – courageous advancement.

I want to thank you, COVID-19, because you allowed me to see a blessing – [people] facing death with equanimity.The poem was criticized so roundly that it received attention even in the state-run media. Shanghai’s Liberation Daily spoke sharply against the poem’s insensitivity, cautioning that creative works needed to have “a human feel” to find a place in people’s hearts. The official Xinhua News Agency felt obliged to report that the poem had “not only failed to elicit sympathies, but in fact had enraged masses of internet users.” Nevertheless, the same Xinhua report heaped praise on other “great works” clearly manipulating emotions to support Party-state themes, noting in particular this one and this one.

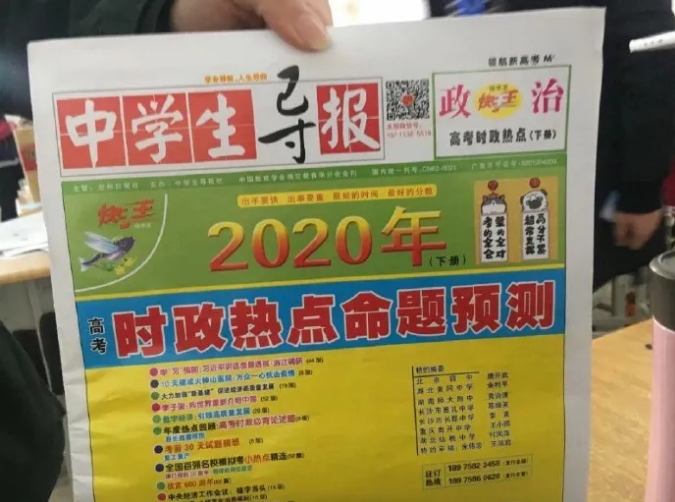

[…] Chinese nerves over being obliged to “eat blood-soaked dumplings” were again tested last week, as the Beijing News and other Chinese media reported that the Middle School Student Guide (中学生导报), a nationally circulated publication for middle school students published by Lanzhou Daily, the official Party-run newspaper in the city of Lanzhou, had run a special issue called “College Entrance Exams: Predicting Hot Topics in Current Affairs” that included a particularly noxious coronavirus inspired poem. […]

[…] The poem caused outrage across Chinese social media, and a commentary from The Beijing News called it “inhuman.” “In the end, a disaster is a disaster, and should not elicit songs of praise and embellishment,” it said. “Nor should distorted writings that describe disasters as good things appear in newspapers circulated to schools.” [Source]

CDT Chinese editors have archived a deleted NetEase News WeChat post on outrage over the poem served to secondary students across China, and similar works. The article–which contains excerpts of coverage from The Beijing News (cited by Bandurski), and ThePaper.cn–has been deleted for violating regulations, and is translated below:

“I will leave, I will return to America. When I arrive in America, I’ll be home.”

– At Last, the Coronavirus Weeps

Last month, the nursery rhyme “Truly Magical Fangcang [Makeshift] Hospitals” flooded the internet, and some media bluntly said that it left many people with goosebumps.

People didn’t expect that a work even more magical and thrilling than the “Truly Magical Fangcang Hospitals” would appear again–and that it would be printed in the widest circulating newspaper for secondary school students and spread widely on campuses.

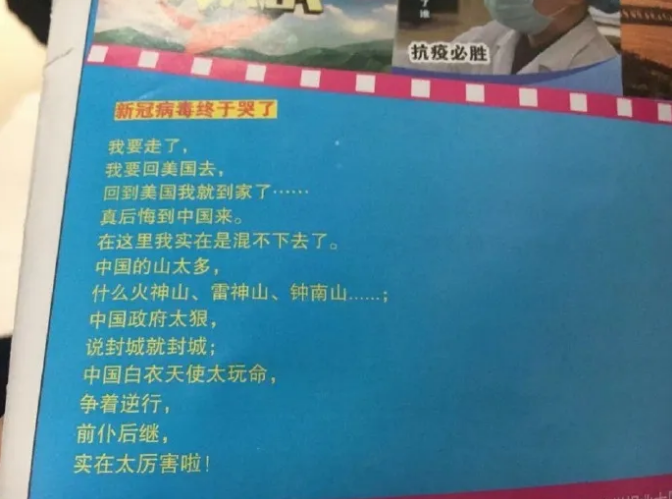

At Last, the Novel Coronavirus Weeps

I will leave,

I will return to America,

When I arrive in American, I’ll be home.

Truly regretted my stay in China.

I‘m unable to stay here any longer.

There are too many mountains in China,

Huoshen Shan, Leishen Shan, and Zhongnan Shan ……;

The Chinese government is too resolute;

If they say the city will be closed it will close;

China’s white-coated angels of mercy are too selfless,

One by one,

They embraced the uphill battle,

With true formidability!

This quickly stirred up a heated online debate. Some education bloggers said such articles indoctrinated hatred, and some history bloggers shared the news that related discussion was already fermenting outside of the mainland.

Media | Please Keep These “Poisonous Poems” Far Away From Our Children

Since the epidemic started, although there has been ceaseless publication of all kinds of amazing works, for example “Thank You, Coronavirus,” “The Bloodshot eyes of the County Secretary and Commissioner Turn Into Spring Flowers,” etc., but these outlandish writings aren’t having much impact–on the contrary, they’re becoming objects of ridicule.

What sets “At Last, the Novel Coronavirus Weeps” apart is that the Middle School Student Guide that carried the piece is a national second-class publication with a massive country-wide circulation–note that “second-class” is currently the highest rating for education newsprint.

You can imagine how many children read this work, thirsty for “spiritual nutrition.”

In my opinion, this poem–which anthropomorphizes the coronavirus and is written in the first person–is highly toxic.

It’s even scarier than the “I Didn’t Know China was So Powerful Without X” type of articles, because not only is it full of self-indulgence and lacking sympathy, it also provokes opposition and hatred, and fosters hostility in children. It’s even more cruel to children than that “Congratulations America on the Epidemic” banner hanging in that congee shop.

It’s surprising, this type of “poem” being published in a standard teaching aid and overtly entering campuses. This is tantamount to a defamation of the word “education.”

Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore said: “The purpose of education should be to convey the breath of life to humanity.” Education should make people benevolent, open their minds, and help children develop their character.

Middle School Student Guide’s public objectives are: “Seeking quality, accuracy, truth, and newness.” But now, the writing it publishes easily crosses beneath the line [that delineates the] underlying values of a civilized society [as stated by the publisher].

To put it more precisely, this “poem” is oriented not to produce caring and rational citizens who respect common sense, but to lead students to be unable to differentiate between right and wrong, and bring prejudice to their worldview.

To a certain degree, it’s precisely this kind of soil needed to “cultivate national hatred,” leading to the practice of taking joy in other tribes’ calamity, hanging red banners “Celebrating America’s Epidemic,” or wishing the virus a “Long Life” in Japan. These practices are essentially contrary to human nature, and opposed to the community-minded response of “joining together to fight the pandemic and target the virus.”

In the end, a disaster is a disaster, and shouldn’t be extolled or beautified, just as this type of distorted work portraying disaster as positive should never be published in newspapers and spread around campuses.

After all is said and done, an explanation from relevant parties about how this human-nature-twisting article made it into the Middle School Student Guide is owed to every parent.

I also need to appeal here: Please, keep this type of “poisonous poem” far away from our children. Just don’t poison them.

Extension | Fangcang Makeshift Hospitals are Truly Magical

“The Fangcang hospitals are truly magical, treating diseases to save people with skill. The doctors and nurses are endlessly talented, each bringing a song to a patient.”

The children’s song “The Fangcang Hospitals are Truly Magical,” lyrics by Tan Zhe, composed by Bu Wenzheng and Jiang Junrong, arranged by Bu Wenzheng, and sung by Fan Mingxuan. The Xiong Feng-directed song is part of the “Hunan People, Hunan Songs” by the Xiaoxiang Poetry Society of Changsha, Hunan. […]

Media | The Creation of Art Cannot be Cannot be Out of Touch with Real Life

Elsewhere in literary and art creation, these days there’s a documentary trending, “Chinese Doctor,” whose value of artistic form and expression far exceeds “The Fangcang Hospitals are Truly Magical.” The first Chinese medical culture documentary from the point of view of medical staff shows different aspects of the profession from different perspectives, and includes joy, sorrow, optimism, and helplessness. “The Fangcang Hospitals are Truly Magical” is, in every way, less reverent, less caring, and more frivolous.

In the final analysis, it is worthwhile to record this epidemic, which came so suddenly, with literary works about all those people on the frontlines, but those works should maintain the basic perspective of human care. After all, maintaining a sense of reverence when facing such a serious epidemic is also the basis of a civilized society. [Chinese]

Tony Hu contributed to this translation.