Speaking at the Herstory conference this March as part of Chengdu’s Women’s Month, prominent women’s rights activist Xiao Meili shared the story of her 2,000km protest walk from Beijing to Guangzhou to raise awareness about sexual assault in 2013. Her speech covered a range of topics, from formative childhood experiences to immortal beings, and how she contended with critics and trolls during her protest walk. Xiao has played a major role in China’s #MeToo movement, both as an activist and a spokesperson for sexual assault survivors. Her speech, eloquent and humorous in equal parts, has been translated by CDT nearly in full. Emphases in italics were added by the translator.

Let Us Be the Tiny Heartbeats of Change

Xiao Meili

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5IHP0taEmVk

Hi everyone,

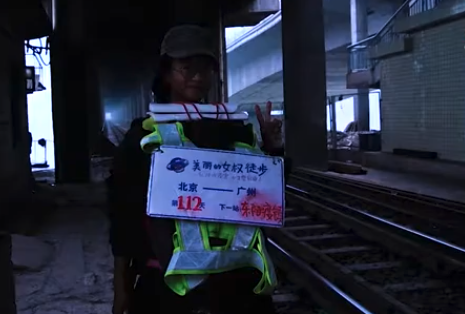

My name is Xiao Meili. In 2013, I did a crazy thing. I walked from Beijing to Guangzhou. Which is to say, I made the entire journey without using a single form of transportation except my own two legs. The distance from Beijing to Guangzhou is 2300 kilometers, and it took me a total of 144 days. In these 144 days, my hair grew 12.2cm, I had my period six times–it was always on time. I went through six pairs of shoes, I got sick once (diarrhea), I got lost twice, and I got into arguments with three people.

You might think it’s rather strange: why would someone like Xiao Meili go and do something so arduous and painful? Why would I use such a difficult method to advocate for the prevention of campus sexual assault? Over the course of my walk, just like a train, I carried a road sign: “Beijing to Guangzhou,” as if I could carry someone.

Source: Video

This sign also displayed one more line in small print: “Oppose Sexual Assault, Women Want Freedom.” Perhaps you’re thinking, “Are you some kind of hardcore outdoor enthusiast?” In fact, I’m really not–quite the opposite. Normally I’m the kind of homebody who never does any exercise. To ensure that I could complete this journey, I only began training a few months prior, out of a real fear that I would collapse and die while on the road.

I thought to myself: “This long hike seems to be the second time in my life that I’ve dedicated myself to a physical activity for so long.” So what was the first time? It was middle distance running. For a lot of people, perhaps the 800-meter dash was a nightmare, but when I was in primary school in the fifth or sixth grade, I especially loved middle distance. Why did I have such a peculiar affection for it? It was because I was an incredibly lonely child. I was a kid who moved from the countryside to Chengdu for school. I think, as a child, I probably had a fairly strong country accent when I spoke. Regardless, for various reasons, my childhood was very, very lonely. Lonely to what extent? I know a lot of people also probably feared ghosts as children, but when I was a child I didn’t fear them at all. Sometimes, I would actually hope that we would have a ghost in our home. Because having a ghost was better than having nothing at all. Perhaps also because at that time, I already knew that people were often scarier than ghosts.

So in order to survive amid this loneliness, I put a lot of effort into many trying many things–middle distance running was one of them. In the fifth or sixth grade, I would get out of bed around five or six in the morning and head over to the university fields next to our home to run a few laps. I particularly loved how when my body reached its limit, after my thighs felt like they had lost all feeling, during that period of time when I would entirely rely on my own willpower to keep moving, I would feel extremely present and grounded. I also loved that excited and happy feeling after intense exercise. I thought it was great.

But this happy feeling didn’t stay for long. One morning, I went running, and an uncle came up to me and struck up a conversation, so we went running together. He even bought me breakfast–I still remember, it was soy milk and steamed buns. The following day, again I went running, and again, that uncle ran with me. I wanted to show off to him and said “I’m going to go do some sit-ups on the parallel bars.”

The secret to succeeding at sit-ups on the parallel bars is that you have to sit above the bars, placing one leg on top of each bar, feet pointing upwards. Holding your posture, with each hand gripping the opposite bar, use your abdomen to flip backwards, until the upper half of your body is hanging upside down from the bars.

But that day was different from other days–I hadn’t tucked my shirt into my shorts. So my shirt flipped upwards, exposing my still-developing breasts. At that moment, I felt a powerful sense of shame. I became very aware that I was a young girl, while the person in front of me was a grown man. This dynamic, to me, felt really dangerous. So I hopped off the parallel bars and ran home.

I never went back to that track again. That uncle hadn’t done anything, hadn’t said anything wrong, but I’m sharing this experience in order to tell everyone that when I think about my childhood experiences, they were a time of great fear and worry. I would even say I was a ball of nerves when I was a small child. Perhaps, because in my eyes this world was enormous and alien and dangerous, I had to be eternally vigilant in order to live. Perhaps you could still make the incisive observation: “Hey, you weren’t even that careful. If you were really so cautious, then why did you go running alone, let alone talk to a stranger? It’s lucky that nothing happened. You’re very lucky.”

Yes, I really was very lucky. I grew up lucky and safe. But what is behind this “luck”? It is the burden of being eternally fearful and anxious about other people. It is the potential happiness that I gave up, those immeasurable sunk costs. I suspect that many women are just like me–we understand this feeling of fear.

That feeling you get when you’re walking home alone at night and hear footsteps behind you.

That feeling you get when you’re taking the subway and feel someone’s backpack brush up against your bum.

That feeling you get when you’re in the elevator of your own apartment building with a stranger, and you don’t dare press the button for your own floor.

So when I say that I’m “lucky,” really what I want to say is, I just happened to be lucky. Because for all that we sacrifice and bear in order to grow up safe, really what we rely most on is luck.

Going back to the year that I made my walk, 2013. That year, I graduated from college. At the time, there was this sensational piece of news: at a primary school in Hainan Province, six girls had inexplicably disappeared. Their parents and teachers searched furiously for them, searching for an entire night, to no avail. Later, they discovered that the school’s principal, Chen Daipeng, had taken the girls to “rent a room.” In addition to the principal, Chen Daipeng, there was also an official with the housing administration who had taken two of the girls to “rent a room.” At the time, I remember seeing this news and feeling absolutely furious. I felt that this was an incident that everyone should’ve been indignant about, shouldn’t it?

But very quickly, I saw a report in a mainstream newspaper which used extra large font in its headline to write: “We must pay close attention to the deviant lifestyles of these six primary school girls,” implying that the girls’ behavior was a form of misconduct. While they condemned this principal and the housing official, people were also saying: “We need to better monitor our children, prevent them from running around.” I thought to myself: these children weren’t just “running around!” They were in school! They were in a place where children were supposed to be. Where they should have been safe.

I was filled with all kinds of doubt. That year, 2013, I wanted to give myself some time to experiment and travel, I wanted to take a meaningful “gap year.” So I thought to myself: what should I do in order to make the most of this year? I read online about a person who walked from Shanghai to Beijing, and thought to myself “wow, they’re so cool.” And then I thought, “hey, what would it be like if I embarked on my own journey by foot?” But the second thought that appeared in my head was a worry: “What if I’mraped? What if I’m trafficked?” Had I had those worries today I probably would also have thought: “Would I be kidnapped and forced to serve as someone’s surrogate?”

So I approached some of my new female friends to discuss this idea. We also discussed what was the hot topic at that time, which was this Hainan principal’s “room renting” incident. I discovered that I, like many others, had many misunderstandings about the issue of sexual assault. We thought that sexual assault was a kind of harm that happened in environments where the perpetrators had no ability to control themselves, those extremely rare, dangerous, bad people–particularly bad men–who targeted young women who didn’t follow the rules.

In reality, this is far from the case. Crime is actually a very rational action. These people behave this way not because they fail to understand that their actions are wrong, not because they fail to understand that their actions will hurt other people, but because they can. Because it is worthwhile to behave this way. Because it incurs few costs for them.

I thought, perhaps we misunderstand sexual assault. What is “real” sexual assault like? I wanted to understand this issue. I discovered that the vast majority of sexual assault takes place between people who know each other, or in situations between two people with clear power differentials. Because that way, the perpetrators can better control their victims, ensuring that they don’t speak out. Therefore, in order to understand and resolve the issue of sexual assault, we have to approach it from the perspective of power. This is the perspective that we need to adopt to view and resolve this issue.

But what does our society tell us is the way to resolve this problem? We’ve created all-female subway cars, as if to shame all men and say: “You’re all sex-crazed wolves with no ability to control yourselves.” Hence these innocent lambs need to be placed in a nicely demarcated area where they will finally be safe. Because the rest of the world is comprised of uncontrollable sex maniacs. Our society even wants to construct sealed school campuses. We hope that students won’t casually enter and exit their dormitories, and we send teachers on endless rounds of inspection. Regulating students will always be easy. But what about the teachers? What about the principals? What about those people with even more power? Who regulates them?

I truly believe that in this gender-unequal society, to force the weaker party to accept even less freedom and space will only empower the perpetrators, not the opposite. We can’t lock up potential victims if we want to change society.

To change society, we shouldn’t expect victims to have perfect moral characters, or resolve the problem by locking them up–this is an incredibly complicated issue. We have to affect change from the skeleton that is the system, to the flesh that is our culture, to the nerve endings that are every individual’s thoughts.

I thought that in comparison to this change, my dream of walking across China was incredibly small. So small as to be like a tiny heartbeat. In 2013, I thought, after reading about the blowout affair that was the campus “room renting” incident, what next? I saw an opinion column in Southern Metropolis Weekly, which read: “Recently, frequent incidents of women in college being sexually assaulted occurred because these victims didn’t have self-protective instincts.” CCTV’s commentary said “college women are often sexually assaulted because they’re just too greedy.” At the time, there was a very popular essay being shared in my friend circle, which unironically carried the headline: “When women are about to be murdered, give the murderer a good reason not to kill you!”

I am truly furious. I do not understand why when our society is sick, we demand that its victims take the medicine. I have endured enough of these victim-blaming narratives. But at the time, I felt that I was just a fresh college graduate, without any resources or methods to get other people to listen to what I had to say. And I returned again to that sense of isolation I felt as a child. I thought, this world has so many people, why is it that we are still so lonely? Why is it that when we’re on a busy sports field, when we walk onto a cramped subway car, when we enter into familiar office environments, it nonetheless feels like we’re entering into a wilderness inhabited by monsters and beasts?

But I think the absolutely most fortunate thing is that, when people like me grow up, we remember those episodes, and we aspire to change them. I have a great wish: I want to become that tiny heartbeat. But unlike in primary school, I am no longer that lonely girl on the field. I’ve grown up. I have friends. I have a particularly wise friend. When I told her my crazy plan, she immediately said to me: “Xiao Meili, if you’re going to make the walk, I will walk with you.” Her name is Lü Pin. I have another friend who is particularly active, called Datu, who said, “If you’re going to walk, I will meet you at the destination, and organize a show for your arrival.”

After several months of preparation, I finally began my walk. I discovered this act of walking became quite concrete. Things I had previously feared, being assaulted, being trafficked, etc., were actually not the most immediate dangers. What were the immediate dangers? Traffic and air pollution. What’s more, the beautiful landscapes that I had so looked forward to seeing on the way, really looked more like this:

Source: Video

The first thing that I had prepared properly for this walk was my body. Before this walk, I never noticed the slight irregularity about the flesh on my toes. After I began this walk, every day, they called out to me: “Pay attention to me! Pay attention to me!” by constantly forming blisters. Then, after a few days, the blisters would break. After breaking, they would scab. After scabbing, they would form calluses. Then blisters would form on the calluses.

The second thing that I had prepared properly for this walk was my knees. I spent an enormous amount of time thinking: “Why do people have to have knees?” Because my knees were truly in great pain. Only later did I realize that walking is really a technical activity. You need your bum–the two largest muscles in the human body–to move your two legs. You have to use your core, you have to straighten out your chest, to use your arms to direct your body. One step at a time, I walked from Beijing to Zhengzhou, from Zhengzhou to Wuhan, from Wuhan to Changsha, from Changsha to Guangzhou. Every step sculpted my body. I felt that the exercise produced in me a particularly marvelous reaction: I felt that it changed my personality.

Having completed this walk, I discovered that I became more self-assured, more cheerful. I took more initiative, and felt a greater sense of security in myself. Over the course of the walk, I lived in a total of 12 people’s homes and 137 hotels, the cheapest costing only 10 RMB. I can still remember that 10 RMB hotel, because I suspect the owners had never once changed the bedding. Sleeping there that night, whenever I shifted my body, a vaporous mist would spray into the air, and the mist would fall on my face, choking me awake.

So a lot of amusing things happened on this trip. All in all, over the course of this walk, 52 people joined in to accompany me for varying lengths of time. One of those people was named Ma Hu, who accompanied me for 106 days–this photo is of the place we ate instant noodles together. She walked with me from Zhengzhou all the way to Guangzhou. Over the course of the walk, I made a lot of friends, and experienced a lot of goodwill from strangers.

Just after I had entered the limits of Guangzhou, I passed by a lake called “Nanshuihu.” It was extremely pretty, one of the few pretty landscapes I saw during this trip. But this lake was really far too large, and there was nowhere nearby to get anything to eat. Walking along this lake, staring at the water, so blue, so green, emanating a faint mist, releasing water vapor like a big bowl of instant noodles. I thought to myself: “Wouldn’t it be great if this lake had immortals?” So I began to make a wish: “If this lake has immortals, I wish for 200 RMB and two box lunches.”

So I continued walking with Ma Hu, and suddenly a car pulled up and stopped. A man stepped out, looking like he had just had his hair done–it looked great, so I called him “Stylish Brother.” “Stylish Brother” listened to our situation, and then pulled out his wallet, saying: “I don’t have much, but here, have 200 RMB,” before going his own way.

So then Ma Hu and I kept walking until it was nearly dark, and then suddenly another car pulled up and stopped. A person stepped out–it was “Stylish Brother” again, bearing two box lunches. So we placed our box lunches on top of the fence surrounding the lake – the concrete fence was solid. “Stylish Brother” parked his car behind us, switching on the headlamps to give us some light. He stood in the gap between the concrete fence and the car. That night, the wind was especially strong, messing up “Stylish Brother’s” stylish haircut. “Stylish Brother” said: “Let me help you block the wind for a bit.”

At the time, I was truly moved. In addition to experiencing the goodwill of strangers, I also got to know many netizens through journaling and uploading my cartoons of amusing encounters on the trip.

Years later, meeting people in real life, many say: “Xiao Meili, I know who you are. I started paying attention to gender issues, all because I followed your walk.” There isn’t much else that could move me more than hearing this.

But in addition to this goodwill, I also received a lot of malice. I remember that it wasn’t that long after I set off that I received a DM on Weibo. Someone said to me: “Xiao Meili, if you dare walk this way, when you get to Wuhan, I will rape you.” This never actually happened, but I feel bad for Wuhan.

While on the road, because I really wanted to share my message with others, having done such an awesome thing, I really hoped that someone would come to report on it. So at every stop I would try and get in touch with local media. I think perhaps at the time, this issue was too new for our country, and people couldn’t really understand what I was trying to do. So media coverage was fairly limited. But a reporter with Time Magazine reached out to me–at the time, I was over the moon. So I shared the message on Weibo. Immediately, friends online reached out to say: “This person could be a con man, you know, that type of person that calls you and says ‘I’m with Time Magazine, give me 1000 RMB and I’ll interview you.'” So I was suspicious that it was a scam. But eventually a Time journalist really did show up. It wasn’t a scam. And my story really did get published in Time Magazine, I thought it was just awesome.

Later on, the Time story was translated back into Chinese for domestic mainstream media. After that, I discovered that a ton of people were criticizing me. Criticizing me for what? They said: “You’re too ugly. That’s why you’ve managed to walk this far without being raped.” They said those things as if to say that being sexually assaulted and being raped is a certainty for women. If this was a certainty, I imagine nobody would want it to be. There were also a lot of people who criticized me, saying: “China doesn’t have a sexual assault problem, neither does it have your so-called victim blaming issue. So why would you embark on such a strange trip like this? And why would your story earn a report from an American news organization?” Can you guess why? Because I’m a “foreign force.” So I tried to understand these people. I thought, just like how I believe “Stylish Brother” was sent by the immortals in the lake, perhaps they also believe I was sent by foreign powers.

At the end of my walk, I spent three months traveling to more than ten cities around the country, giving around 20 public speeches, discussing the issue of sexual assault. I sent gift packets about preventing sexual assault to every provincial and municipal education ministry, hoping that they would study up on the topic. I even designed a sexual harassment prevention logo, hoping that it would be added to subways and public transit systems.

Because I majored in design, in college I opened a Taobao store, Dupin, which means “independent character.” I hoped to design some women’s rights-related goods. This top I’m wearing is one of the items available in our store.

But when I designed this item of clothing, it was primarily because I personally wanted to wear something like this, and I wasn’t sure whether other people would buy it–perhaps only a few. But since 2014, people have been buying it continuously, and it’s even been exhibited at Columbia University’s Barnard College.

After that, my energy has remained focused on advocating for women’s rights. In 2018, the Me Too wave reached China. Many women and also men came out to share with the public their experiences of sexual assault and harassment, hoping to seek justice for themselves. During this time, endless voices condemning the victims reappeared, and I became a spokesperson, joining many debates where taking sides and plot-twists were expected. I even made a podcast with a friend called Into the Fields (有点田园), where I hoped to discuss some down-to-earth gender perspectives, as well as complicated gender issues.

In recent years, I moved back to Chengdu because I believe it’s a great city with great diversity and tolerance and which values spiritual culture. This is one reason why I’m participating in Chengdu Women’s Month.

[…] One last thing I want to say is, society’s 2300km comes one step at a time. Society’s change comes from a single stitch, a single thread, with every social media “like,” with every tear, with every time we retreat into the monologue inside our hearts. Regardless of whether you are speaking out online or taking action offline, or making speeches, videos, or cartoons, I believe we can all become starting points for change. We can all be that tiny heartbeat.