The following censorship instructions, issued to the media by government authorities, have been leaked and distributed online. The name of the issuing body has been omitted to protect the source.

All websites immediately cool down focus on “Uncle” Ou Shaokun’s visit with a prostitute. Do not make it a lead story. Control commentary, and block searches for important related information.* (April 7, 2015) [Chinese]

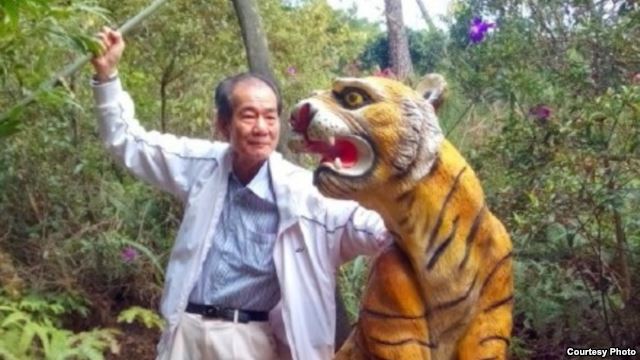

Guangzhou-based anticorruption activist Ou Shaokun, also known as “Uncle Ou” (区伯), was detained for five days late last month in Changsha, Hunan for allegedly soliciting a prostitute. The detention followed closely after Ou posted photos of a Guangzhou government SUV in Hunan on unofficial business, and Ou’s supporters immediately suspected that his detention, and the unusual official verification of his identity to the media, came in retaliation for his activism. Following initial coverage of Ou’s detention, propaganda authorities ordered that media not “hype” the story. After being released, Ou Shaokun denied that he had solicited a prostitute, said that his confession had been coerced, and claimed that a local television station had aired a portion of it out of context.

Acting on suspicion that Ou had been set up, Ou’s supporters fired up the “human flesh search engine.” While still speculative, evidence circulated that Chen Jialuo (陈佳罗), the man who had invited Ou out to karaoke where he met the woman who would later be found in his hotel room, could actually be Captain Chen Jianluo (陈检罗) of the Changsha Domestic Security Department. Chen Jialou had introduced himself to Ou as a manager at a local media company.

Also see the South China Morning Post’s translation of an essay by journalist Chang Ping on how public support of Ou shows disapproval for “shame parades,” exemplified by televised confessions.

*The above censorship directive’s usage of the language “important information” appears to be in reference to Captain Chen’s name. Searches results for Chen Jianluo (陈检罗) are currently blocked on both Baidu and Weibo. Back.