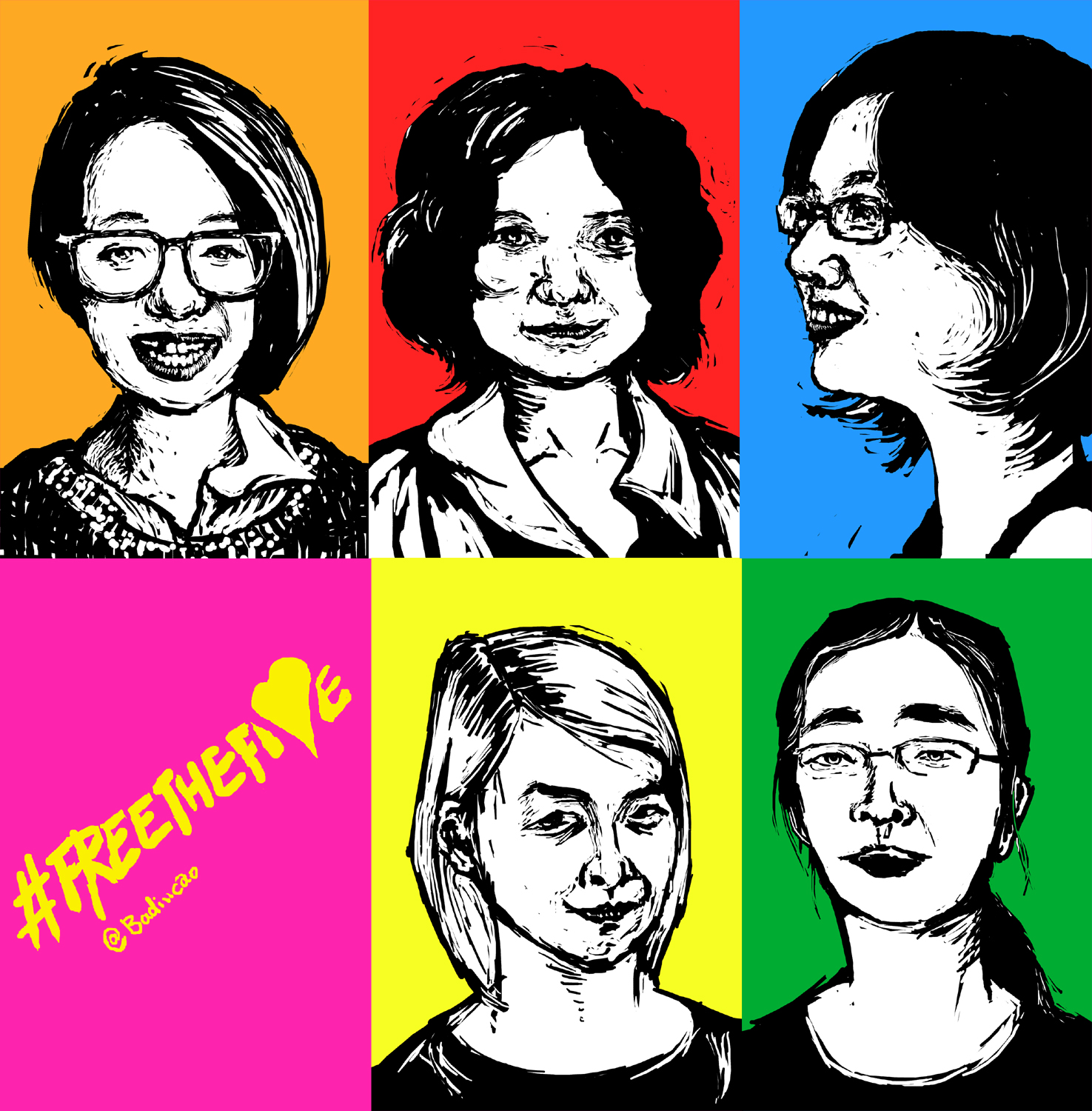

A women’s rights NGO associated with two of the five activists detained in March has been shuttered due to government pressure following their release. Vanessa Piao at the New York Times reports:

Wu Rongrong, one of the five detained women and the founder of the Weizhiming Women’s Center in Hangzhou, China, said she had no choice but to shut down the organization on May 29 after four of her six full-time employees and most of the center’s volunteers left after they and their families came under police investigation

Zheng Churan, another of the five activists detained just before International Women’s Day, when they planned to campaign against sexual harassment on public transport, had served as Weizhiming’s project manager since its founding in August 2014, Ms. Wu said in an interview on Friday. Ms. Zheng had explained that she could no longer work for the group because of the tremendous pressure she felt while in detention and since the women’s release in mid-April.

Ms. Wu said that work at Weizhiming was largely suspected after she was detained on March 7 and the organization’s office was searched, as most staff members left and those who remained feared that working on advocacy campaigns could lead to further detentions. The group’s funding, which came mostly from local and overseas foundations, ran out, Ms. Wu said, and they could no longer pay their rent after May.

“I thought things should be fine as there weren’t a lot of questions about Weizhiming,” she said, referring to police interrogations. “But after I was released, we found it was just impossible for us to do our work.” [Source]

Another high-profile, anti-discrimination group affiliated with the detained activists, Yirenping, also faced official harassment when their offices were raided by police. Despite this, Chinese authorities signed an anti-discrimination pledge for its bid for the Winter 2022 Olympic Games. Adam Rose of Reuters reports on a press conference in which the Olympic bid committee was asked about the harassment of Yirenping:

In March, Chinese police raided the office of a well-known non-governmental organization in Beijing called Yirenping, a group which works to banish gender, HIV and other forms of discrimination. The NGO had campaigned for the release of five women activists, who were detained in the same month. They were later released, but remain under close watch.

“I have never heard of the people or organizations you’ve mentioned,” Wang said, when asked how the anti-discrimination pledge was compatible with the crackdown on Yirenping.

“You might be better informed than I am,” she added. “I really don’t know.” [Source]

The crackdown on these two groups coincides with a broader effort to restrain the activities of Chinese civil society groups. In the Los Angeles Times, Timothy Cheek and Jeffery Wasserstrom write about how an apparent gradual shift toward more liberal policies and a more open society—what journalist Ian Johnson called “China’s slow-motion revolution”—appears to have stalled:

As recently as 2009, this slow-motion revolution still seemed alive. The party did tighten control in 2008 as it strove to ensure that the Olympic Games went well. And the party always dealt ruthlessly with organized challengers. But the watchword was, as a bartender summed it up to one of us: Meiyou yundong, shenme dou keyi — if it isn’t a movement, anything goes.

Writing in 2009 to mark the June 4 anniversary, Lijia Zhang, who marched in 1989, described the situation well. Twenty years before, she said, people like her had felt trapped “in a cage” and longed to be free. Since 1989, the bars of the cage had moved farther away. They knew that the cage still existed, but it was easier to imagine that it didn’t.

Xi Jinping seems to believe he must stamp out all hints of dissent in order to save China from the instability that has beset various post-communist societies.

Today, however, the bars are closing in again. Many rights lawyers and moderate civil society activists have been jailed. In March, five feminists were summarily detained in Beijing with no legal process, solely for planning events publicizing the need for greater equality. Censorship of the Internet has increased. Chinese academics have been warned to watch what they say in class. They should not promote “Western values” or “threaten social stability” by talking about social inequities and historical mistakes made by the party. [Source]

Another key step in this movement away from the “slow-motion revolution” is a draft law aimed at further restricting the activities of foreign NGOs, which would also have a deep impact on domestic civil society groups. Last week marked the end of a consultation period for the law, during which several lawyers and human rights groups submitted critiques and suggestions. At the South China Morning Post, Verna Yu summarizes some of the concerns about the law:

A staff member at an international NGO operating on the mainland, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorised to speak to the media, said he was worried about the considerable power given to police to oversee foreign NGOs and the domestic NGOs that work with them. “It’s rather like having a sword above your head, and you’re not entirely sure how close it is to you,” he said.

According to the draft, police have a say on the annual assessment of foreign NGOs, which determines whether the groups can continue operating. If police investigated an NGO, they could enter its premises, seizing documents and information. The officers could also examine the organisation’s bank accounts.

The NGO staff member said that in order to survive, many NGOs would probably steer clear of projects in areas that the authorities deemed sensitive, such as democracy and rights. The layers of supervision required by the law, including those overseeing temporary activities, would also stifle international NGO cooperation with domestic partners, he said. Even if a foreign NGO managed to get registered, it could get into trouble for working with unregistered domestic partners, he said.

Amnesty International warned that organisations would not be able to predict what kind of activities would run afoul of the law because of the draft’s subjective terms, such as “endangering China’s national unity, security or ethnic cohesion”. [Source]

A broader coalition of 45 American business and professional groups wrote a letter to the Chinese government stating their concerns that the law as drafted would damage U.S.-China relations. Gillian Wong at the Wall Street Journal reports:

The letter, reviewed by The Wall Street Journal, was signed by 45 groups representing industries ranging from technology to agriculture to entertainment. They include the American Apparel and Footwear Association, the American Petroleum Institute, BSA The Software Alliance, the Motion Picture Association of America, the National Association of Real Estate Investment Trusts, the U.S. Grains Council and U.S. Meat Export Federation, among others.

[…] In their letter, the groups said the scope of the law was overly broad, including in its definition of “nongovernmental groups” trade associations, overseas chambers of commerce, and professional associations, a move that the groups said could severely impact Chinese commerce and industry. They also raised concerns it would put management of such groups under the Ministry of Public Security, suggesting that Beijing sees the groups as a potential threat. Currently such groups work closely with a variety of commercial and other agencies.

The law, “if enacted without major modifications, would have a significant adverse impact on the future of U.S.-China relations,” the letter said. [Source]

Legal scholar Floria Sapio has posted a commentary on the law which suggests that rather than merely posing a threat to foreign NGOs, the law as drafted also presents an opportunity for NGOs to examine whether their work is carried out in the most efficacious way in China, stating: “The NGO law is an opportunity for funding agencies and NGOs to pause and ask themselves whether, in trying to deliver a message that is highly compatible with the needs expressed by the Party-state and by Chinese society, they are really speaking the language that best highlights the similarity and compatibility of their respective goals.”