Following the recent U.S. airstrikes on Syria, Chinese state media denounced the move by President Trump, staying true to Beijing’s commitment to non-interference. Responding to a question on whether the attack appeared to represent a U.S. policy shift towards pursuing regime change in Syria, China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs spokesperson Hua Chunying responded: “We believe that the future of Syria should be left in the hands of the Syrian people themselves. We respect the Syrian people’s choice of their own leaders and development path.” At The Washington Post, Isaac Stone Fish points out the irony in this response, considering that neither Syria nor China allow the people to democratically choose their own leaders. Stone Fish continues to examine the motives behind Beijing’s “astonishingly obtuse claim” to oversee a democracy—one that Xi Jinping has been known to make even as he reinforces the authoritarianism of the country he leads:

So why does China still call itself a democracy? Making this claim allows Beijing to legitimize its own actions — and, in the case of its views on the U.S. missile attacks, the Syrian government’s — as representing the will of the people. This hoodwinking and hypocrisy has served Beijing well. “Imagine calling yourself the People’s Autocracy of China, or the Glorious Autocracy of China,” said Perry Link, a professor at the University of California at Riverside who has studied China’s human rights issues for decades. Alternatively, he said, the People’s Republic of China, or, for example, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea — the official name of North Korea — shifts the burden of proof to the other side to show that the country is not, in fact, democratic.

Yes, Beijing means something different with the word “democracy” than Americans do — and this has a lot to do with the Chinese Communist Party’s ideological origin story. Vladimir Lenin preached “democratic centralism,” a system where supposedly democratically elected officials dictated policy. Similarly, Mao called for the “people’s democratic dictatorship” — a dictatorship by the people, for the people, allegedly far superior to the “bankrupt” system of “Western bourgeois democracy,” where elites plundered the working class. In her 2015 essay “The Populist Dream of Chinese Democracy,” the Harvard University political scientist Elizabeth J. Perry contextualizes Chinese democracy as more akin to populism. She quotes Xi Zhongxun, the former propaganda chief (and the late father of China’s current leader), who once exhorted fellow party members “to put your asses on the side of the masses.” […] [Source]

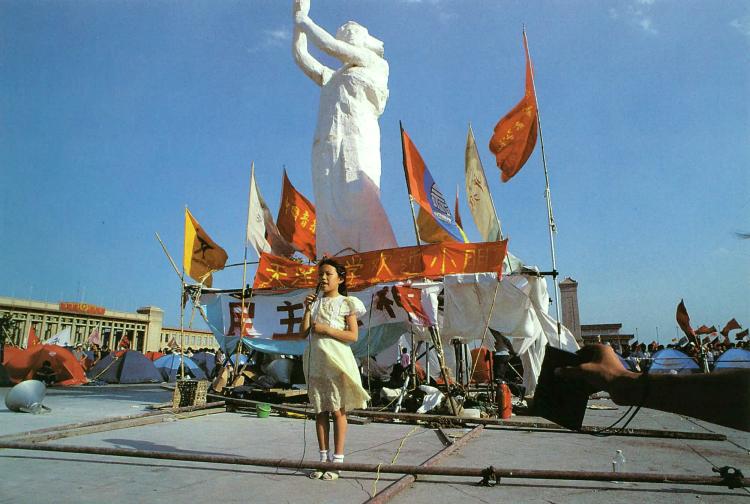

Late last month, on the eve of the first meeting between President Xi and President Trump, Asia Society’s Orville Schell asked if it was time to abandon expectations that China’s political system would liberalize and democratize. After acknowledging that the hopes present (if often battered) since the PRC’s reform era seem harder than ever to maintain amid steady crackdowns on the media and liberal ideology, Schell provides some historical perspective on democracy in China. Looking to the future, Schell notes that “just because prospects for another political revolution are difficult to see right now, we should not assume that China has reached an end point in its development.” From The Wall Street Journal:

[…S]ome historical perspective is in order—not because Mr. Xi shows any signs of relenting in his oppressive agenda but because it would be a mistake to confuse the present reality with permanence. Democratic ideals have deep roots in modern Chinese history and have surfaced again and again over the past century. This legacy should serve to remind us that not all Chinese, even in the worst of times, have been resigned to a politics of one-party rule.

The idea that China would develop into a constitutional republic was first and most forcefully proposed at the beginning of the previous century by Sun Yat-sen, the so-called father of modern China. Sun had studied in Hawaii, converted to Christianity and become a medical doctor before starting his campaign against dynastic rule. When his republican government replaced the collapsed Qing Dynasty in 1912, he called for “three phases of national reconstruction,” starting with a period of martial law, followed by an interlude of “political tutelage” and culminating in constitutionalism. “Without such a process,” he insisted, “disorder will be unavoidable.”

Sun’s concerns about the difficulty of even starting to implant liberal democracy in China were quickly confirmed. His presidency lasted just 41 days as the country slid into the control of regional warlords. But Sun persisted, going on to establish the Nationalist Party, whose role in promoting democratic ideals in China proved to be long and tortuous.

[…] Throughout his own trying decades as president of the new Republic of China in the 1930s and ’40s, Chiang Kai-shek, who succeeded Sun Yat-sen as the leader of the Nationalist Party, was no model of democratic practice, often suppressing opposition and basic civil liberties. In theory, however, he never wavered in his devotion to Sun’s road map to constitutionalism, insisting that, after the necessary period of “tutelage,” the Nationalist Party would “carry out its original purpose and return sovereign power to the people.”

[…] As for China itself, the ideal of a more open society governed by law would not be fanned back to life until after Mao’s death in 1976. When Deng Xiaoping issued a clarion call for a new agenda of “reform and opening” and “the liberation of thought” in 1978, many in the West were tempted to hope that China might now get back on track to evolve just as Sun had imagined. […] [Source]