The practice of containing information not approved by the government has long been commonplace in China, and has steadily intensified both in traditional media and online under the leadership of Xi Jinping. Amid a global focus on China’s reaction to the novel coronavirus that originated in Wuhan and has so far infected (by the official count, which some have questioned) 28,000 people and killed 563 in China, commentators have blamed China’s rigid autocracy as a cause of the outbreak and its quick spread. Many have pointed directly to the systemic use of censorship as a major public health risk intensifier. Local authorities were slow to respond to the first cases and stifled information by penalizing frontline health workers–itself characteristic of the national environment of censorship and intimidation. While public anger boiled over authorities’ ability to contain it briefly last month (and also created temporary “creative coverage” opportunities for quality professional and citizen journalism), central authorities are reportedly planning to further tighten information controls.

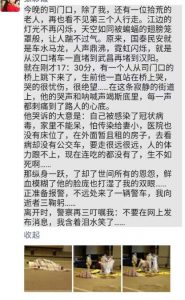

According to a February 2 WeChat Moments post shared by an anonymous Wuhan resident, local police in Wuhan are issuing verbal warnings not to share information about the fallout of the disease and the city’s current lack of resources to handle it. A screenshot of the Moments post has been archived and translated by CDT:

Tonight at Simen Gate, aside from me there was an elderly person collecting scraps. Besides the two of us, I didn’t see another person

walking outside. The lighting along the riverbank was no longer on, and the sky looked like it had been enveloped by a bat’s wing, making it hard for people to breathe. Now I understand, life is good when there’s an endless stream of traffic, a cacophony of voices, and the flickering of neon lights; when traffic jams are backed up from Hankou to Wuchang and then to Hanyang. Just now, at 17:30, there was a man who jumped off the Simen Gate bridge, crying incessantly before he did. His tears were laden with grief and despair… On that quiet street his cries and shouts rang out, stabbing the hearts of all passersby.

The main theme of his laments was that he had been infected with coronavirus, that he couldn’t stay at home as he was afraid of infecting his wife and child. Hospitals have run out of empty beds, so he was staying in a rented flat. He needed to visit the doctor but there is no public transit. He had to walk for a long long time. His strength was failing, and now he didn’t even have food to eat, it is better to die than to live.

With that jump, he left behind all his grievances with the world. Blood obscured his face and made me tear up… As I was preparing to call the police a police car came from nearby. I bowed to the deceased three times.

As I was leaving, the police repeatedly urged me “not to share this information online.” I laughed with tears in my eyes… [Chinese]

See also CDT’s translation of a lower-level health official’s description of his frustration at the frontline of relief efforts, or a Wuhan resident’s notes from the Wuhan lockdown. CDT has also translated a propaganda directive ordering the deletion of an article on an infected frontline doctor who had earlier been disciplined for “spreading rumors” about the virus, and an earlier directive to delete a state media report on the potential economic impact of the coronavirus (the deleted article has also been translated by CDT).

walking outside. The lighting along the riverbank was no longer on, and the sky looked like it had been enveloped by a bat’s wing, making it hard for people to breathe. Now I understand, life is good when there’s an endless stream of traffic, a cacophony of voices, and the flickering of neon lights; when traffic jams are backed up from Hankou to Wuchang and then to Hanyang. Just now, at 17:30, there was a man who jumped off the Simen Gate bridge, crying incessantly before he did. His tears were laden with grief and despair… On that quiet street his cries and shouts rang out, stabbing the hearts of all passersby.

walking outside. The lighting along the riverbank was no longer on, and the sky looked like it had been enveloped by a bat’s wing, making it hard for people to breathe. Now I understand, life is good when there’s an endless stream of traffic, a cacophony of voices, and the flickering of neon lights; when traffic jams are backed up from Hankou to Wuchang and then to Hanyang. Just now, at 17:30, there was a man who jumped off the Simen Gate bridge, crying incessantly before he did. His tears were laden with grief and despair… On that quiet street his cries and shouts rang out, stabbing the hearts of all passersby.