Late last week, censors wiped Weibo clean of posts documenting the chaos of pandemic control measures in Lhasa, Tibet. In mid-August, Tibet began reporting thousands of new cases in the region’s first documented outbreak since 2020. Yet there has been a paucity of reporting on the Lhasa outbreak and subsequent lockdown because local journalists are constrained as to what they can publish, and access to the region by foreign journalists remains tightly controlled. In response, residents of Lhasa took to Weibo with complaints centering on six now-familiar aspects of lockdowns: the alleged cover-up of case numbers, shabby central quarantine facilities, food shortages, lack of medical care for non-COVID illnesses, unresponsive government agencies, and general malfeasance. At The New York Times, Vivian Wang reported on the calls for help emanating from Tibet, which outside observers note have little precedent in recent years:

“The social media posts you see from people in Lhasa are all about suffering, but that’s the real Lhasa. Lhasa’s public announcements, I feel they’re all fake,” said a food delivery worker in the city who gave only his surname, Min, for fear of official retaliation.

[…] On Douyin, the Chinese version of TikTok, some residents have shared videos in Tibetan describing being unable to work or pay rent, according to translations by Tibet Action Institute, an overseas activist group supporting Tibetan independence. One man, filming himself in a vehicle, said he had been sleeping in his car for a month. A woman begged to be allowed to return to her village elsewhere in Tibet, describing her worry about food running out.

Lhadon Tethong, the director of Tibet Action Institute, said she had been stunned by what she called a flood of Tibetan voices this week, compared with a trickle of information before.

“They’re these direct cries for help coming from inside in a way that we just don’t see anymore,” she said. “So we know they’re at the breaking point.” [Source]

At What’s On Weibo, Manya Koetse translated a number of the viral posts out of Lhasa:

“I am a bit shocked!” one local social media user wrote: “What I saw was a total of 28 buses lined up outside Lhasa Nagqu No. 2 Senior High School, and then still more [buses] were coming. One bus can fit around 50 people, so there must have been around 1400 positive cases. There was a blind man, there were elderly people in wheelchairs, there were swaddled-up babies, from getting on the bus at 9.30 pm up to now, we’ve been waiting for 5 hours and we’re still waiting now. It’s just pure chaos at the school entrance, there is no order. I won’t sleep tonight.”

[…] “In order to welcome central government leaders to Lhasa and to demonstrate the “excellent” epidemic prevention capabilities of the local government & the “outstanding” results of the fight against the epidemic to them, they moved citizens to the rural areas and let them all stay crowded together in unfinished concrete buildings, with all kinds of viruses having free reign.”

[…] “Please pay more attention to the topic of the Lhasa epidemic,” one person wrote, repeating a similar message sent out by many others: “Lhasa doesn’t need your prayers, we need exposure.” [Source]

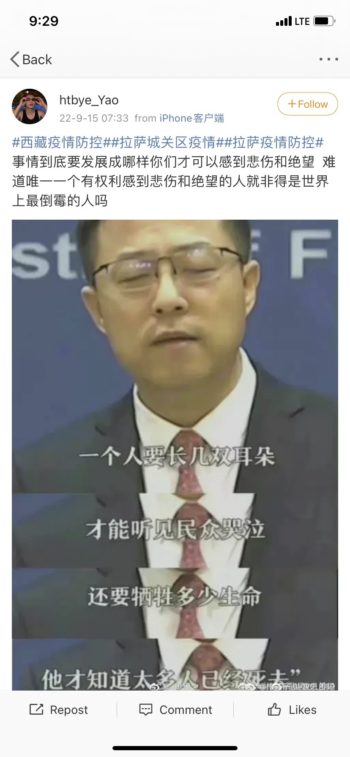

Lhasa netizens also deployed Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Zhao Lijian memes to criticize the government’s COVID response. During the Shanghai lockdown, a viral image of a man with a Zhao quote taped to his back sparked an explosion of jokes about the “stolen glee” of living under China’s zero-COVID policy until censors eventually clamped down. But posts from Lhasa again used Zhao meme templates. One shared a screenshot taken from a September 16, 2021 press conference during which Zhao quoted Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” to criticize America’s COVID response: “How many ears must one man have, before he can hear people cry?”

A screenshot of a post from Lhasa using a Zhao Lijian meme

The outpouring was seemingly also inspired by a surge of posts from a similarly hush-hush lockdown in Yining (known as Ghulja in Uyghur and Qulja in Kazakh), the largest city in Xinjiang’s Yili (Ili) Kazakh Autonomous Prefecture. Online discussion of Yili was smothered by a campaign revealed by leaked directives from local authorities. Brigades of “internet commentary personnel” were deployed to drown out stories of lockdown suffering with “a campaign of comment flooding” on a Weibo Super Topic dedicated to Yili. The Public Security Internet Monitoring Department threatened those spreading “negative energy” with arrest, and described the campaign as part of a “smokeless war.” Local media outlets were also instructed to record scenes of “children having fun and smiling seniors” for broad distribution across news sites and social media.

While similar directives have not yet emerged for the Lhasa lockdown, a similar playbook seems to be in use. A hashtag used to document events in Lhasa was wiped clean by censors, who removed tagged posts from public view. The tag was then flooded with identical posts from the official Weibo accounts of municipal fire departments across the country, which shared a short propaganda film produced by China’s national Fire and Rescue Department Ministry of Emergency Management hailing Lhasa’s “flaming heart” frontline volunteers. These surges are a form of Weibo censorship derisively termed “Operation Blue V” by netizens, a tongue-in-cheek nod to the Chinese action movie Operation Red Sea and the blue “V” checkmarks borne by verified government accounts:

Weibo also seemingly censored the “topics trending in your city” function for Lhasa, as the city had only one trending topic—a state-sponsored hashtag reporting only two new cases—while other cities experiencing lockdowns, like Chengdu, had dozens:

Side-by-side screenshots of Weibo’s “trending in your city” function for Lhasa and Chengdu, which seem to indicate Lhasa’s was being censored on Friday, September 16.

In recent days, state media outlets have begun publishing pieces hailing Lhasa’s “return to work,” with one businessman telling CGTN: “Pandemic control has been effective. As one of the business owners here, I’m very happy to see this.” The official Weibo account of Lhasa’ propaganda arm posted a song by Tenzin Tsondu (known as Ding Zhen in Mandarin), a Tibetan herder whose charisma and good looks helped him rocket to overnight fame on Douyin. The song included the lyrics, “But I’m thankful to have you in my life, / carefully lighting every torch for me. / Thank you for each and every time you’ve given me / the clearest direction and light,” interspersed with gifs of white-hazmat-suited “Big Whites” standing beneath the Communist Party flag or spraying Lhasa with disinfectant under a rainbow of their own creation: