Information control and national security have long gone hand in hand for the Chinese government, especially under Xi Jinping. Last year was marked by a notable increase in government attempts to restrict information flows in and out of China in the name of national security, with authorities raiding foreign firms, imposing exit bans, closing databases, and expanding an espionage law. As various media outlets have recently highlighted, these trends have only intensified.

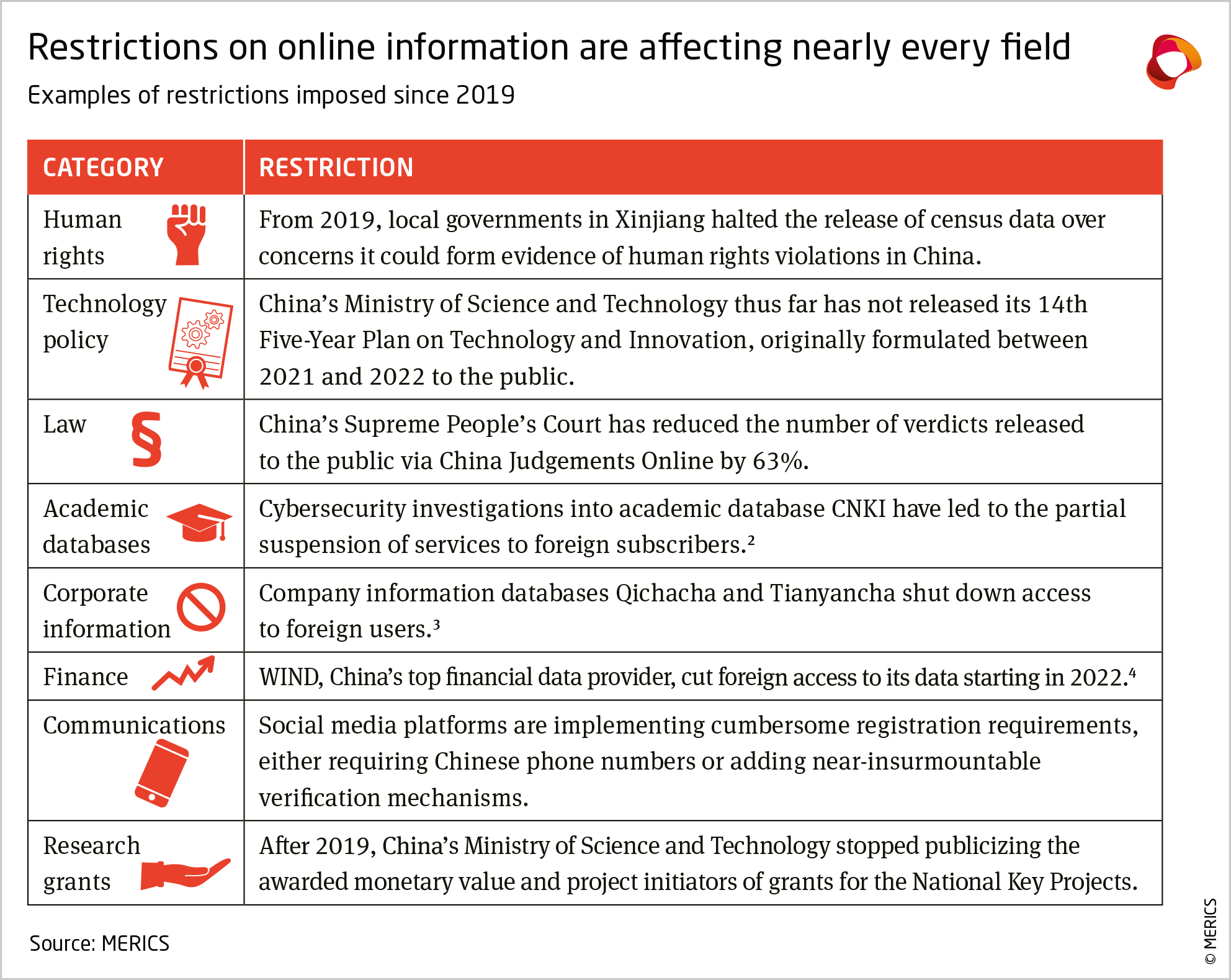

This week, MERICS published a report titled, “The increasing challenge of obtaining information from Xi’s China.” As described by the authors, Vincent Brussee and Kai von Carnap, the Chinese government is restricting foreign access to crucial information on contemporary China across numerous sectors, in large part due to geopolitical and purported national security concerns. In addition to highlighting different metrics that trace the fall in government transparency and examining the limited but expanding scope of targeted information, the report also provides case studies demonstrating the increasingly effective technical means used to block foreign access to information on the Chinese internet, and discusses the implications of a more restricted information space for global analysis and discussions of China:

Online information from China is disappearing, though with differing impact depending on sensitivity and strategic value. In fields like science and technology policy, human rights, and other sensitive domains, access to information is demonstrably regressing. In fields more closely related to most Chinese citizens’ daily lives, transparency remains high. Similarly, while a few crucial databases and sources are restricting foreign access with increasingly effective means, many popular websites and information services remain available with limited constraints. Still, many data access challenges are linked to less overtly geopolitical motives, such as personal information protection or website updates.

This shows that China’s authorities are more aggressively curtailing information potentially related to an ever-expanding notion of national security but strive to keep everything else relatively open. The party still sees transparency as an important tool to enable a functioning economy, improve its legitimacy, and fight corruption. And to the outside world, a fully closed-off Chinese internet would harm the image of “responsible power” it is trying to convey and openly contradict the narrative of a “shared destiny for the future of mankind in cyberspace.”

Authorities are also keenly aware that they cannot just remove information; they must fill the void with new information and knowledge. This is the push to “tell China’s story well,” in the words of Xi Jinping. Hence, reducing access to certain information and then filling the void with pro-China narratives are two sides of the same coin.

[…] Global discussions of China will increasingly coalesce around a narrowing set of source materials. One likely consequence is an amplification of extreme viewpoints, especially the beliefs that China is about to collapse and take over the world at the same time. The government will show observers the big plans but not the (often messy) implementation, while protests will continue to make headlines abroad but the mixed perceptions that many citizens have of the state may remain veiled. With fewer sources at our disposal, finding a middle ground will become increasingly difficult. [Source]

In another recent piece providing more evidence of these trends, The Economist tracked declining cross-border exchanges, notably of foreign tourists coming to China, Chinese students studying in the U.S., and Xi Jinping traveling abroad:

At the most basic level, far fewer outsiders are crossing borders into China. Last year the country recorded about 62m fewer entries and exits by foreigners than in 2019, before the pandemic began—a drop of more than 63%.

[…] China’s state-controlled media like to highlight examples of American mistreatment of Chinese people. Such cases serve a propaganda campaign that portrays the West as racist and a builder of barriers and of menacing security networks that are aimed at keeping an innocent China in its place. Perhaps intentionally, this depiction of the West may be deterring some Chinese students from going to America: in the academic year of 2022-23 they numbered about 290,000, down from a peak of more than 370,000 in 2019-20.

Mr Xi likes to present his own country as a champion of global engagement (in a world laden with doubt about globalisation, he describes it with striking confidence as an “irreversible trend of the times”). In reality he seems less inclined to travel abroad. In 2023, after the better part of three years without venturing overseas, he spent only 13 days outside the country, compared with a more typical 28 days in 2019. In September last year he shunned an annual gathering of G20 leaders in India, despite having attended previous such events in person or online. [Source]

Last month, RFA reported that the CCP is “taking a direct role in the running of universities across the country” by merging the presidents’ offices with embedded Party committees in order to form a “unified” leadership for higher education. In a ChinaFile conversation on the subject, several commentators argued that the resulting restrictions on academic freedom will likely hinder the CCP’s own goals related to the development and global competitiveness of Chinese higher education:

Sun Peidong: The CCP’s increasing control over universities is a regressive step for academic freedom and innovation. While the Party’s intentions might be to safeguard its rule and ideological purity, this approach is likely to stifle creativity, critical thinking, and intellectual advancement. In Asia Society’s recent report, “China 2024: What to Watch,” economist Diana Choyleva finds Xi Jinping’s prioritization of “comprehensive national security” over economic growth, coupled with a revival of Marxist-Leninist ideology, is at odds with China’s development objectives. In essence, Xi’s regime prioritizes Communist Party control, even at the expense of economic progress and fundamental freedoms. As historian Antonia Finnane remarked in her book How to Make a Mao Suit: Clothing the People of Communist China, 1949–1976, a nation cannot simultaneously encourage innovation in technology while restricting fundamental ideas in politics. This paradox within the communist system only tightens the noose around its own neck, ultimately suffocating the very vitality it seeks to protect.

[…] David Moser: […T]he Party’s strategy is obviously counterproductive to China’s own aspirations of building world-class, soft-power-enhancing universities. Though certain elite Chinese universities have steadily risen in the world university rankings, over the long term top-notch universities cannot thrive without international cooperation. Despite the enticement of lucrative salaries, Chinese universities have failed to attract eminent foreign professors as prestigious fixtures of the faculty. The many study-abroad programs that were suspended during the COVID epidemic have not returned, partly due to the doubts about the usefulness of increasingly censored curricula. With enormous budgets and state funding, China will undoubtedly be able to attract academic talent and cooperation in areas such as AI and genomics, but the prospect of Chinese Harvards or Oxfords is still very much in doubt. [Source]

Also last month, Tom Grundy from Hong Kong Free Press reported on another instance of government restrictions on information, when Hong Kong’s Department of Justice deleted an online database of national security cases just days after it was published:

The index, published last Thursday, included PDF case summaries relating to 106 national security law cases that have been completed since Beijing inserted the legislation into Hong Kong’s mini constitution in June 2020.

However, the index had disappeared soon afterwards, according to a Sunday newsletter from local news platform TransitJam.

[…] “This body of case-law helps us understand the requirements of our national security laws and how they are being applied by the courts,” the Secretary for Justice Paul Lam was quoted as saying.

The department [of Justice] did not respond when asked why the content was removed and whether it would be restored. [Source]