In Chinese, Xiang (翔) means “flying.” It is also Liu Xiang’s given name. Since China’s “Flying Man” limped off the National Stadium track on Monday, the state’s propaganda machine has been running at full speed to manage his national image. Liu Xiang is more than a sports star, he has been the poster-child of China’s Olympics over the last four years. His performance and publicity is a significant part of “China’s biggest image project” – aka the Beijing Olympics. Chinese internet censors have been deleting negative online comments about Liu Xiang since the day before yesterday, not to mention that China’s Vice-President Xi Jinping already sent words of comfort to Liu, and all official media and online news portals have set a uniformly sympathetic tone in reporting this story.

“Liu remains the national hero despite the pullout,” a Xinhua headline screamed.

But many netizens still post their doubts and disappointment in their blogs and online forums. To find such expressions, one just needs to search the phrase “Liu Xiang” (刘降) in Chinese. It is a different character for “Xiang” (降), meaning “surrender,” even if the pronunciation is the same as the character for “flying.” So just search “Surrender Liu” instead of “Flying Liu” in Chinese, and you will see those discussions that Chinese propaganda authorities wish to make disappear online.

Kevin Garside also writes in the Telegraph:

We should not be surprised. The episode illustrates the game China is in. The Olympics in Beijing are an exercise in impression management, a £1 billion-plus ad. Appearances are everything.

It was not Xiang who was competing but China itself. China could not be seen to be weak, impaired or flawed. Having spent seven years and ten figures reworking its public image, China could not afford to be without the central figure around which the narrative is spun, the man who has come to embody the new China.

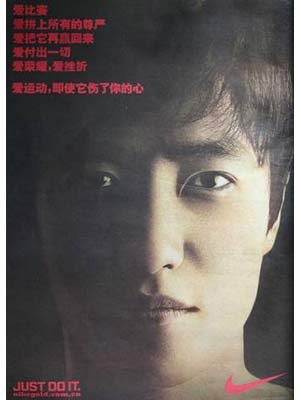

The Nike/China caption read: Love competition. Love risking your pride. Love winning it back. Love giving it everything you’ve got. Love the glory. Love the pain. Love sport even when it breaks your heart.

Love the schmaltz. The ad’s creative directors missed a trick. They should have left the tears in. The syntax of these Games is layered with faux sentiment. China’s rank and file, the billions on message, are not equipped to decode the literal meaning. The boy even apologised for letting down the people. Ye gods.