The following censorship instructions, issued to the media by government authorities, have been leaked and distributed online. The name of the issuing body has been omitted to protect the source.

Without exception, the media are not to report on:

- The delegation from Myanmar visiting China

- The documentary “Under the Dome” winning an environmental award

- Three propaganda arrangements concerning the Oriental Star:

- Increase positive propaganda on humanitarianism, use Xinhua News Agency copy

- Control entertainment sections and advertisements for Yangtze River travel during rescue effort and time immediately surrounding the disaster

- Strengthen supervision of reporters’ individual Weibo accounts. (June 8, 2015) [Chinese]

Myanmar’s opposition leader Aung San Suu Kyi will visit China for the first time this week, facing pressure to publicly acknowledge the imprisonment of fellow Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo. Last week, Chai Jing’s environmental documentary “Under the Dome,” which achieved massive viral success before its suppression by censors this spring, won an award from China’s Society of Entrepreneurs and Ecology.

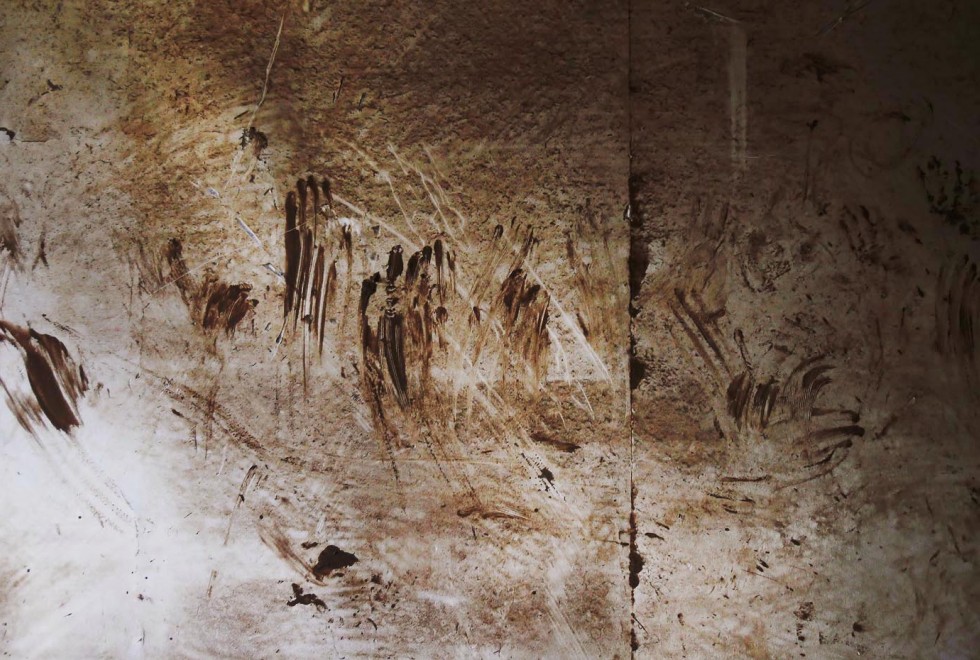

The Oriental Star cruise ship capsized on the Yangtze River on June 1st. The past week has seen both a feverish rescue operation and vigorous information control. Despite early hopes, only fourteen survivors have been found, while the confirmed death toll has risen to over 430. As the events of the ship’s final minutes became clearer, and official pictures emerged from the righted vessel, the cause of the disaster has remained the subject of widespread suspicion. The government has promised a full investigation, and the cruise operator has pledged full cooperation.

On Tuesday, The Wall Street Journal’s Chun Han Wong and Olivia Geng reported the partial deletion under “heavy pressure” of a Beijing News report on one possible factor:

The report in the Beijing News, a leading commercial newspaper in the Chinese capital, said the Eastern Star had received retrofits that made the vessel less safe. “Changes to the ship’s structure and additions to its length made it less stable, and increased the risk of capsize,” the report said, citing company officials and ship inspectors that it didn’t name. It also alleged that the ship’s owner maintained “special” ties with local shipping inspectors, particularly during the periods when the vessel was constructed and retrofitted.

The article’s allegations couldn’t be independently verified. […]

Web-based versions of the Beijing News report, which also appeared in print, became inaccessible by late Monday morning. The article was still accessible via the newspaper’s official account on the WeChat mobile-messaging service as of Tuesday morning, as were copies of the report reproduced by other Chinese news media. The English-language edition of the Global Times tabloid, which is affiliated with the official Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily, also cited the Beijing News’ allegations in a Tuesday report.

[…] Chinese authorities have commandeered the flow of public information related to the disaster, such as by directing domestic media to rely on reports from state broadcaster CCTV and the official Xinhua News Agency, which have sought to portray government leaders favorably and curb speculation. Apart from the Beijing News article, observers say other publications have also removed reports that discussed possible causes of the sinking. [Source]

From Julie Makinen at The Los Angeles Times on Friday:

[…] A spokesman for the Transportation Ministry, Xu Chengguan, has vowed that “we will never shield mistakes and we’ll absolutely not cover up” anything.

But Zhang Xiaohui, a reporter for the Chinese publication Economic Observer, said that he was detained by authorities after going to the ship company’s offices in Chongqing on Tuesday and reporting that he discovered employees shredding documents. Zhang said in a social-media post that he was held under the potential charge of spreading rumors online. [Source]

Makinen’s report also touched on the tension and occasional conflict between officials and relatives of the victims. Since the disaster, family members have faced stonewalling, surveillance, accusations of ulterior motives, and even violence.

For days, [Stella Wu] had sought help and answers about the tragedy at home in Shanghai. She stood outside the local government office until 1 a.m., but staffers would only say that they had no information from the scene and that the leaders were in a meeting. Next, she and other relatives of missing passengers decided to march on a busy street to try to get authorities to pay attention. Police, she said, came and dispersed them, dragging and hitting people.

Finally, she bought a train ticket to Jianli, only to find that people from her neighborhood committee had purchased seats on the same train – ostensibly to help her, but clearly also to keep tabs on her. […] [Source]

Taiwan’s ETTV captured an altercation between relatives and police in Shanghai:

The Wall Street Journal’s Chun Han Wong reported that many relatives were anxious to see their relatives’ bodies before cremation, a process which began on Monday:

Several times in the past few days, Ms. Chen has asked to see the remains of her husband, Zhang Guangren, only to be put off by officials. “I want to see his body,” said the 73-year-old retired native of Nanjing city, who now lives in the U.S. “I don’t care about money or anything else.”

[…] Officials cited public-health concerns and the logistics of dealing with so many bodies as reasons for not letting the relatives see the dead. The remains are being stored in funeral facilities in four separate counties, having overwhelmed the capacity of the sole funeral parlor in Jianli.

[…] The slowness of the process has been confounding. A daughter of Ms. Chen said she and her mother have asked to review any photos of the bodies to see if her father is among them, to no avail.

[…] Nanjing officials sent to Jianli to assist next-of-kin from that city at times seemed to fuel frustration. On Thursday, Ms. Chen and several others confronted an official in a shouting match at a local government building, after he demanded that relatives prove their identities and insinuated that they were in Jianli to seek compensation. [Source]

Reuters’ Sue-Lin Wong and John Ruwitch also reported on the group from Nanjing:

When they arrived in Jianli they tried to walk to the site of rescue operations, but were stopped by police who had accompanied them from Nanjing. Authorities later said they could visit the area in organised groups but reporters and cameramen could not accompany them.

“I can’t rule out that even among Chinese journalists there are people who want to smear the government,” Hu Shining, Nanjing’s deputy police chief, told the relatives who had walked with reporters in tow to try to get to the river’s edge.

[…] A few of the relatives in Shanghai who were part of a news sharing chat group told Reuters they suspected police were pretending to be family members and were posting messages and photos, mainly about government rescue efforts.

“Why would a grief-stricken family member be posting such positive messages about what a great job government officials are doing in Jianli?” said one man whose mother is missing. [Source]

Authorities have tried to keep relatives and reporters apart: video from BBC News’ Martin Patience shows a succession of civilian, police, and military personnel obstructing his efforts to report on a peaceful protest by bereaved family members. But one elderly relative managed to get into a press briefing in search of information, Reuters’ John Ruwitch and Megha Rajagopalan reported:

Frustration over the lack of information has grown among families of the missing. Seventy-year-old Xia Yunchen burst into a just finished news briefing with senior officials on Friday, screaming and demanding answers.

“Is it necessary to treat the common people, one by one, as if you are facing some kind of formidable foe?” said Xia, whose sister and brother-in-law were aboard the Eastern Star.

Xia, from the eastern city of Qingdao, told reporters she had wanted to get into the news conference to hear for herself what the government was saying, and that she wanted an honest investigation because family members doubted the weather was the real cause of the disaster.

“You view the common people as if we are all your enemy. We are tax payers. We support the government. You had better change your notion of this relationship. You are here to serve us. You need to be humane,” Xia said, before being escorted out. [Source]

https://twitter.com/Tajima92/status/606665859658948608/

Drama at #Yangtze capsize press briefing. A woman who says two of her kin were passengers stormed into venue, demands for thorough probe

— Chun Han Wong 王春翰 (@ByChunHan) June 5, 2015

Officials preventing media from leaving briefing venue, as they try to calm relatives of #Yangtze sinking victims outside the gate.

— Chun Han Wong 王春翰 (@ByChunHan) June 5, 2015

Woman who says she has kin aboard capsized #Yangtze cruise ship speaking in press briefing venue. Photo from earlier pic.twitter.com/xwoYY2nXjw

— Chun Han Wong 王春翰 (@ByChunHan) June 5, 2015

Media locked in briefing venue are being offered a bus ride to press center for lunch, to bypass #Yangtze passengers' kin outside

— Chun Han Wong 王春翰 (@ByChunHan) June 5, 2015

Media is free to go. #Yangtze passengers' kin plan to petition officials with demands including right to see remains, thorough probe

— Chun Han Wong 王春翰 (@ByChunHan) June 5, 2015

Demands in #Yangtze kin petition similar to those from woman who burst into briefing venue earlier. Wonder we'll see her on Chinese media.

— Chun Han Wong 王春翰 (@ByChunHan) June 5, 2015

Some foreign media began to find fault with the handling of the rescue effort and aftermath, cherry-picking disappointments and complaints, and weaving contradictions and conflicts around the event. Some eagerly preyed on the suffering of family members, pouring salt on their wounds, and fostering antagonism between those at the centre and around the edges of the events. This is truly unkind.

Because the casualties are so large, and out of respect for the relatives, Chinese society rushed to the rescue, while appreciating the importance of consoling the relatives. When domestic media have preyed on the suffering of relatives after past disasters, they have almost invariably faced condemnation by the public. Very quickly, everyone came to hold this bottom line in reverence.

Foreign media have no need for solidarity with Chinese society. They don’t have to think about helping to solve problems, and like to lay bare collisions and scars within Chinese society. Their way of thinking is often antagonistic. Therefore they have no interest in the whole chain of cause and effect; they just latch onto the most sensational and provocative parts.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be angry with foreign media: these are their rules, driven by their interests. But we must differentiate ourselves clearly, firmly refrain from imitating them, and guard our own principles. [Chinese]

The paper’s English-language edition took a somewhat more positive view on Sunday, however:

While the measures the country has taken are unsatisfactory for some, most of the public has shown understanding. We are not omnipotent in the struggle with death. It’s a cruel display of the fragility and limitation of modernization.

A minority poured out dissenting voices and leveled complaints. But it’s noticeable that they don’t represent the mainstream sentiments of society over the shipwreck.

The foreign media are prone to report those dissenting opinions. However, in view of the swift and effective operation, they have shown restraint in not capitalizing on China’s pains this time. This has rarely been the case over the years. [Source]

Some aspects of state media coverage also came under fire, James T. Areddy reported at The Wall Street Journal:

Coming in for particularly angry criticism was the online version of the Communist Party mouthpiece People’s Daily for a story that introduced a group of navy frogmen under the headline, “Rescue Line: China’s Hottest Men Are All Here.”

“A national tragedy, relatives of the dead mired in pain, and yet People’s Daily uses it for entertainment,” lawyer Zhang Zhiyong wrote on his verified feed on the social-media platform run by Weibo. A search showed what appeared to be hundreds of posts about “hottest men” and the search for the ship. Phones rang unanswered at the newspaper’s office on Saturday.

[…] Web users also directed ire at newspapers in Hubei province, where at least three publications on Saturday published the same emotion-charged photo of workers in white antibacterial suits facing the raised Eastern Star and barges used to salvage it, a scene blanketed in orange as the sun set. The images — generally accompanied with praising text — seemed to some Weibo users as too laudatory of the rescuers amid the death. “How Much I Hope,” said one of the headlines. (The Wall Street Journal also published the photo.) [Source]

The New York Times’ Andrew Jacobs reported that officially sanctioned accounts included some contradictions:

Officials have not given foreign journalists access to any of the 14 people who managed to escape when the ship overturned Monday night, but the state-run Xinhua news agency released interviews with several of the survivors, including the captain and chief engineer.

In an account published by Xinhua on Friday, Wu Jianqiang, a 58-year-old passenger described as an illiterate farmer from Tianjin, said that he and his wife were in their cabin when rainwater began pouring through the windows.

[…] “I could feel my feet slipping from beneath me, but the bed I was on stayed in place,” he said, according to the English version of the article. “So I stretched out my hands to my wife, but our fingers never met.”

[…] Mr. Wu’s account contained a number of discrepancies with the state news media’s reporting on the disaster. He said passengers that day had lingered at the final stop, a tourist attraction along the banks of the river, until 6 p.m. — other accounts said they had returned to the ship seven hours earlier — and the Chinese version of his account described him clasping hands with his wife as the ship began to keel. [Source]

Danwei’s Jeremy Goldkorn discussed censorship surrounding the disaster with Eline Gordts at the Huffington Post on Saturday:

To put it in historical perspective, the Chinese Communist Party has always controlled information about disasters very tightly. The handling of the aftermath of disasters is obviously the government’s responsibility, but there’s also a long-held belief in the country that even the occurrence of natural disasters can in some way be seen as the government’s fault. After the Tangshan earthquake in the 1976, the government basically tried to prevent any spread of information.

The government has been a lot more transparent in recent years, partly because the Internet has made complete coverups impossible. […]

[… The government’s information strategy over the Eastern Star] is successful in limiting any kind of damage to the government’s reputation in the short term, but one of the country’s problems is that there’s a tremendous lack of trust in Chinese society. Most people are suspicious of the story that they’re getting from the government. They usually won’t say that publicly, but one of the reasons why you get people clashing with the police is because they don’t believe what they’re getting told. This happens pretty much every time there’s a disaster of some kind. We saw it this week, we saw it when the Malaysian Airlines plane disappeared and after the New Year’s Eve stampede in Shanghai at the beginning of this year. So it is a successful strategy to minimize any kind of organized threat to the rule of the Communist Party, both in the immediate and long run, but it doesn’t do the Chinese government any good in building a society where there is more trust, both between citizens and also from citizens to the government. People are unable to organize dissent, but they aren’t really going to believe in President Xi Jinping’s much propagandized “Chinese Dream” either. [Source]

At TIME, Hannah Beech suggested that the treatment of relatives, in particular, could prove counterproductive:

Other disasters have made unlikely dissidents out of ordinary Chinese. When parents and others protested the shoddy construction of schools that collapsed during the 2008 Sichuan earthquake, some were jailed for their troubles. When families of New Year’s Eve revelers, who were trampled to death in Shanghai this past holiday, tried to commemorate their loved ones, police and censors converged. Back then, Chinese media were instructed to stick to state-sanctioned versions of events, a pattern that is being repeated with the Eastern Star sinking.

That has prompted some ferry relatives to speak anonymously to the press or to merely identify themselves by their last name. Yet again, personal tragedy was left submerged under the weight of preserving social stability. [Source]

Family members at least found support from the local population, according to Reuters’ Megha Rajagopalan and Joseph Campbell:

The 1.5 million people of Jianli, which sits on a bend of the mighty Yangtze River in the central province of Hubei, have offered free food, car rides and even hair-dressing services to the relatives, rescuers, officials and reporters who have rushed there after the ship carrying more than 450 people sank in a storm on Monday.

Residents have tied bright yellow scarves to their arms, car mirrors, buildings and gates to show solidarity with those impacted by the disaster.

“This is a way for us to show how much we care for those people, especially the families,” said a taxi driver surnamed Luo, who had festooned his own car with billowing scarves. [Source]

Since directives are sometimes communicated orally to journalists and editors, who then leak them online, the wording published here may not be exact. The date given may indicate when the directive was leaked, rather than when it was issued. CDT does its utmost to verify dates and wording, but also takes precautions to protect the source.

Since directives are sometimes communicated orally to journalists and editors, who then leak them online, the wording published here may not be exact. The date given may indicate when the directive was leaked, rather than when it was issued. CDT does its utmost to verify dates and wording, but also takes precautions to protect the source.